‘Hidden cost’ of energy and transport could add up to $25 trillion, research estimates.

Exclusive: New global synthesis adds up the hidden social, environmental and health costs of our largely fossil fuel-based energy and transport systems.

The “hidden cost” of our largely fossil fuel-based energy and transport systems could add up to around $25 trillion (£18 trillion) – the equivalent of more than a quarter of the world’s entire economic output.

That’s according to new research, which estimates the hidden environmental, social and health costs associated with different forms of transport and electricity generation.

There are many “hidden costs” associated with these systems, which occur from production to end use by humans, the researchers say.

For example, the burning of fossil fuels for electricity generation not only drives damaging climate impacts such as more frequent and severe extreme weather events, but also deadly air pollution.

Our global reliance on petrol vehicles is also fuelling climate change and air pollution, as well as an increased strain on our health systems through car accidents.

These impacts are not reflected in the market price of fossil fuels, explains Prof Benjamin Sovacool, an energy policy researcher from the University of Sussex and lead author of the new research, which is published in the journal Energy Research & Social Science.

He told The Independent: “The research centres around ‘externalities’ – a very fancy term for saying hidden costs. Externalities are anything that aren’t reflected in the price of a good or service. We wanted to gain a bold global view of these externalities by collecting as much evidence as we could, over 20 years across all peer-reviewed data.

“What we found is that these externalities are far higher than what we thought – roughly $20 trillion-plus for mobility and energy. That’s around one-quarter of the world’s GDP lost.

“It really underscores just how much energy and transport systems are destroying ecosystems and communities with their monumental impacts on human health, species, jobs, traffic congestion and a whole variety of other hidden costs.”

For the research, the authors carried out a “meta-analysis” that brought together the results of 139 studies.

Many of these studies had come up with cost estimates for individual coal power plants or for just one mode of transport or electricity generation. The new research brought all of these estimates together to come up with a global figure, said Prof Sovacool.

It finds that the hidden costs of the global energy sector are likely to total around $12 trillion, while the costs associated with transport could amount to $13bn.

However, it is worth viewing these figures cautiously, he says. This is because the research combines studies that use vastly different methodologies – and, so, there is a wide range of uncertainty surrounding the estimates.

“The $25 trillion figure is just the mean. We have a wide range – the lowest range is close to zero and the highest range is above $100 trillion,” he said.

The figures include the hidden benefits – or “positive externalities” – as well as the hidden costs, he added.

“Energy systems do have positive externalities as well. For example, they can create jobs” said Prof Sovacool.

“But what’s interesting is that all of the energy systems we examined have net negative externalities – meaning there are more negatives than positives. The only exception to this is energy efficiency measures, which have net positive externalities.”

As part of the analysis, the researchers compared the likely hidden costs for different forms of electricity generation.

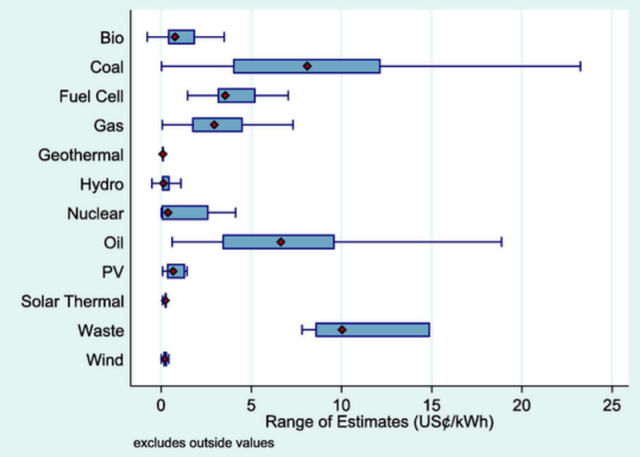

The chart below shows the average hidden costs – or negative “externalities” – for different types of electricity generation, including biomass, coal, hydrogen (fuel cell), gas, geothermal, hydro, nuclear, oil, solar power, solar thermal, energy from waste and wind power. (Externalities are shown in cent per kilowatt hour.)

(On the chart, the red diamond shows the median estimate, while the box-and-whisker plots show the range of results from the different studies included in the analysis.)

(Sovacool et al. (2021))

The chart illustrates that the highest hidden costs are associated with burning waste for energy (such as through incinerators) and coal-fired power.

By contrast, renewable forms of electricity such as wind, solar and geothermal power had the smallest hidden costs.

Study author Prof Jinsoo Kim, an environmental economist at Hanyang University in South Korea, said: “Our study clearly reveals oil, coal, and waste in electricity portfolios generate far more externalities than alternative sources of supply.

“If you factored in the true cost of fossil fuels, the multinational giants that dominate this sector would be huge loss-making operations. Instead, it is left to society and governments to pick up the considerable bill.”

The research estimates that, if negative externalities of coal were taken into consideration, its market price would be more than twice as high as it is at present.

In the research paper, the authors call for policymakers to do more to ensure the price of energy and transport systems more accurately reflect their social and environmental costs.

“The thing that’s really tragic with these externalities is it isn’t that we don’t pay for them,” said Prof Sovacool.

“It’s just that we don’t pay for them on our energy bills, we pay as a society through hospital admissions, premature deaths, degraded landscapes and pollution.

“So we’re saying we should have a price for energy and transport that matches its cost.”

There are various ways that this could be achieved, he added. “There are lots of tools you can use such as carbon taxes or energy taxes, or more energy efficiency measures.”

Dr Chris Krekel, an applied economist at the London School of Economics (LSE) who was not involved in the research, said comparing the negative externalities of different sources of energy was “useful”, but agreed that the central estimate of $25 trillion should be viewed cautiously.

“An aggregate headline figure is probably less helpful than a disaggregated figure by source,” he said.

He added that the new research could have included more studies that look at the hidden costs of energy and transport from the perspective of how these systems can affect people’s wellbeing.

“I think this is an important omission, especially considering that people’s life satisfaction should be the ultimate outcome policy should care about,” he said.

27 February 2021

INDEPENDENT