Guest post: Why Africa’s heatwaves are a forgotten impact of climate change.

Recent summers have demonstrated dramatically that heatwaves are not only deadly, but they are already being influenced by human-induced climate change.

Research into heatwaves across the world has confirmed that increasing trends in frequency, duration and cumulative heat have accelerated since the 1950s. The biggest increases have been seen in the Middle East, South America and parts of Africa.

Other studies have found similar changes when looking at extreme heat stress in low-latitude countries, with sub-Saharan Africa often being identified as a particular hotspot.

Climate projections over the continent also show that heatwaves will continue to become hotter and more dangerous, even if global warming is kept below 1.5C. Combined with population changes, 20-50 times as many people could be exposed to dangerous heat in African cities by the end of the century.

Despite these risks, extreme heat events in sub-Saharan Africa are not routinely monitored. As we explain in a commentary for Nature Climate Change, this means that heat-related deaths are chronically underreported – putting even more people in danger.

Database gaps

Heatwaves – past, present and future – are a fact of African life. However, the large body of supporting scientific literature is in stark contrast with the near-absence of reported heatwave events over sub-Saharan Africa in disaster databases.

These databases list technological and environmental disasters across the world, from extreme weather to earthquakes and oil spills, and record their impacts on lives, livelihoods and economic costs.

The largest of these databases is the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), which was launched in 1988 by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in Belgium.

While heatwaves are by far the deadliest weather-related disasters in Europe, EM-DAT lists no more than two heatwaves in sub-Saharan Africa since the beginning of the 20th Century, leading to 71 recorded premature deaths.

In contrast, 83 heatwaves were recorded in Europe over the same timeframe, contributing to more than 140,000 associated deaths. The picture does not look any different in other inventories of weather-related disasters.

In short, heatwaves in Africa are not reported, despite the fact we know that they are happening. We also know that exposure and vulnerability to extreme weather is often much higher in sub-Saharan Africa than Europe. Therefore, there is likely to be very large numbers of premature deaths from severe heat that have never been registered as such.

Why does it matter?

A lack of reporting on deaths associated with heatwaves means there is little awareness that extreme heat can be so deadly.

The 2003 summer heatwave in Europe offers a tragic example. Only after this heatwave killed more than 70,000 people did nation states, counties and cities implement heat action plans and other measures to minimise risks in the next heat event.

Similarly, the Indian city of Ahmedabad implemented a heatwave plan after an extremely hot and deadly pre-monsoon season in 2010. This meant that when an even more intense heatwave hit in 2015, there was a significant decrease in “excess mortality”. (This is the number of extra deaths compared to what would be expected for that time and place.)

This kind of forward planning is impossible if heatwaves are not recorded. Not only does it seem to require a wakeup call to start implementing heat action plans, but, to be effective, such plans also need to be designed for the region in the world they protect, as well as be combined with early warnings of forthcoming heat events.

Heatwaves are very different in different parts of the world. For example, a 2018 heatwave in Canada killed many people when temperatures reached 34C. Yet such a heat threshold would not even trigger early warning systems in Ahmedabad, since social structures are adapted to temperatures well above 30C in India.

Since heatwave mortality has never been reported in sub-Saharan Africa, we do not know the thresholds that result in heat-related mortality. And this information is crucial for African societies to adapt appropriately.

Why have heatwaves been ignored?

Not only might heatwaves in Africa be characterised by different temperature thresholds compared to other parts of the world, but the duration of extreme heat they might expect to endure could also differ.

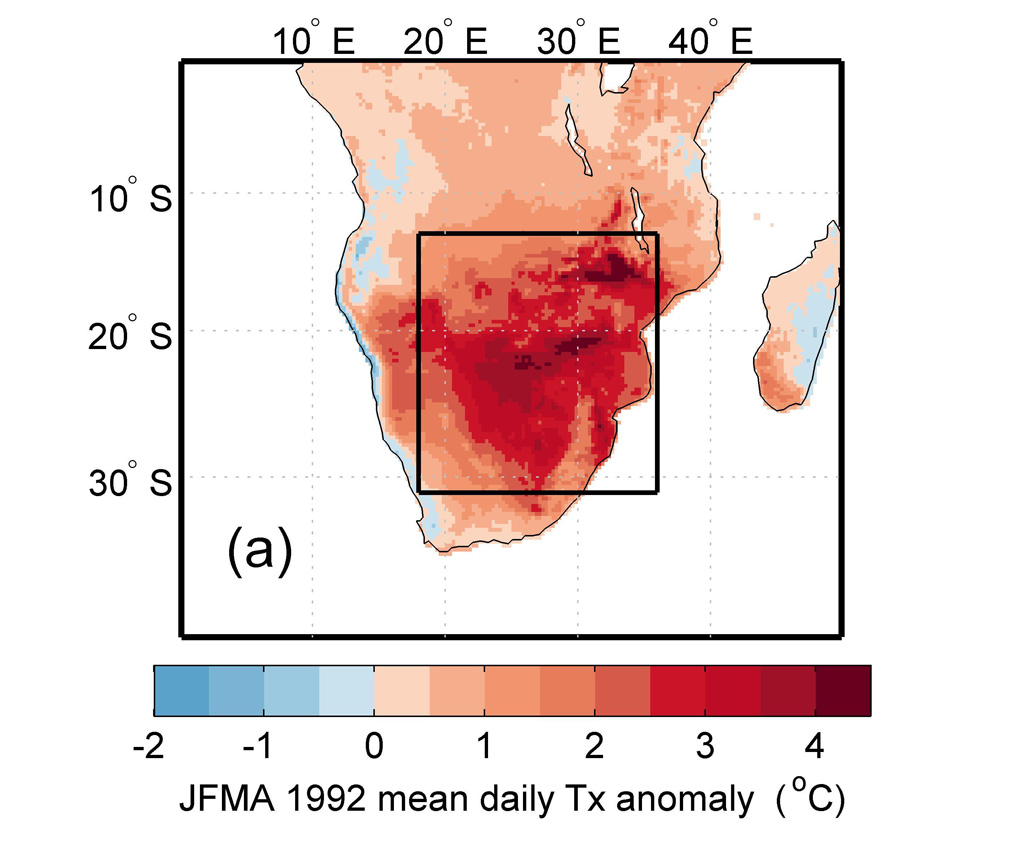

The latter could be one reason why heatwaves have been overlooked in the past. In 1992, a large region of southern Africa – including Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Lesotho and most of South Africa – recorded temperatures of more than 3C above average for a period of four months.

While no impacts associated with this extraordinary heat have been documented, this event coincided with one of the most widespread droughts ever seen in the region.

Droughts have always been a fact of life in sub-Saharan Africa, often leading to humanitarian crises which are recognised and acted upon by the population, governments and NGOs alike.

Compounded with other extremes – such as drought – heatwaves might, thus, be much harder to recognise than if occurring on their own, especially if their characteristics are different from heatwaves in higher latitudes.

Himba woman and children working carrying water to a village. Credit: Graham Prentice / Alamy Stock Photo.

Another reason for the lack of reporting of extreme heat lies in which entities are actually reporting the impacts of extreme weather.

In most developed countries, national governments provide numbers on affected people, mortality and, in some cases, even economic losses for extreme weather events. In contrast, for many low-income countries these reports are provided by different NGOs with little or no connection to meteorological services. Thus, a central place where reports on the nature of the event and its impacts are coming together is lacking.

This makes it much more difficult to identify extremes – particularly when their nature shifts in a changing climate.

Finally, a further reason is that global databases on extremes – and analysis of their impacts – is largely carried out by research organisations in western nations. This means that there is a bias towards events in these countries.

What can be done?

Despite these difficulties, the value of concentrating efforts to identify and report heatwaves and their impacts in Africa remains clear.

Not only would it help to avoid excess mortality during heat events, but it would help to better characterise compound climate extremes – in particular, heat and drought – in one of the world’s most vulnerable regions.

In our paper, we identify three key areas to focus such efforts:

- Building on pilot projects in Ghana and the Gambia, collaborations between local researchers, hospitals and epidemiologists can enable the identification of direct health impacts of extreme heat. Combining this with information gathered from heat-related power outages and transport disruptions could help to improve heatwave identification in sub-Saharan Africa.

- The introduction of early-warning systems – even if initially using triggers developed in climatically similar countries elsewhere – could increase awareness and accelerate learning about how to best characterise local heat extremes.

- More analysis is needed on historical periods of extreme heat from a purely meteorological standpoint. This would provide a third line of evidence towards a relevant and usable definition of heatwaves in African countries.

Heatwaves are killers – and because they affect the most vulnerable, often by compounding the effects of other medical conditions, they kill silently. But when reliable data is combined with local expertise, the impacts of heatwaves can be predictable.

From experiences we’ve seen elsewhere, this foresight could prevent thousands of unnecessary deaths as global temperatures continue to rise.

*Harrington, L. J. and Otto, F. E. L. (2020) Reconciling theory with the reality of African heatwaves, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0851-8

13 July 2020

Carbon Brief