‘Green’ is a Useless Word for the Climate Movement.

There’s a common DNA between political and marketing campaigns, and it’s not always a useful thing. It’s an outgrowth of capitalism that political campaigns are often engineered like marketing campaigns to sell a product if you will. By extension, polling data and focus groups are used by businesses and political campaigns about what voters prioritize. According to Gallup, that old favorite, the economy, was still firmly within the top 5 most important issues in the U.S. as of January 2020.

It’s polled at the same level for Republicans, Democrats and Independents for ages though. Every candidate packages this talking point about the economy and jobs. Whether or not it has any substance though, is like asking whether or not food with ‘organic’ on the label will extend your life, regardless of what else is in your diet. The question isn’t whether organic food is better for you or not, it’s about your diet, and whether or not you’re sticking to it. Maybe you just buy food with ‘organic’ on the label because it because it made you feel better.

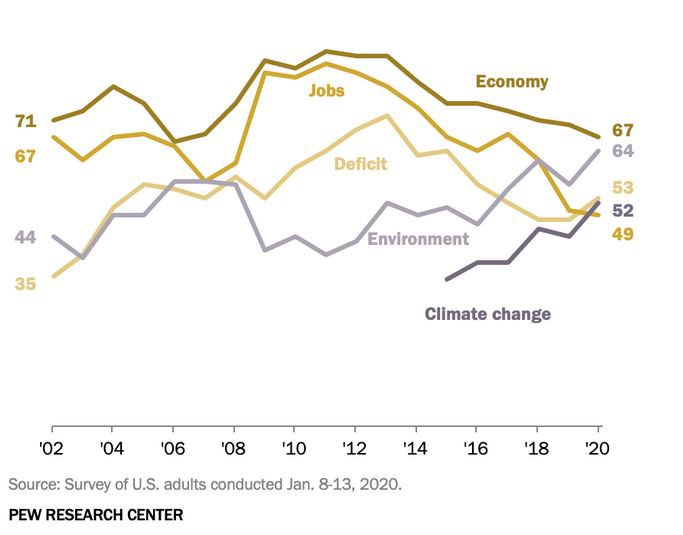

There are tangible issues that can’t be dealt with by taking a placebo though. A recent Pew Research poll found that for the first time in their extensive history of polling, that concern about the environment is rivaling concern about the economy. This is a notable development, but at the same time I wonder about how the various solutions to our environmental concerns poll. There’s a really strong tendency for folks to engage in either analysis paralysis with Google at their fingertips, or latching onto contrarian ideas.

How we talk about these solutions, and how we campaign on them is really not helpful a lot of the time. Specifically when environmentalists and climate activists use the term ‘green’.

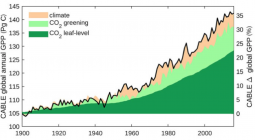

Sure, the term ‘green’ was solid branding throughout much of the Obama administration. It was brought out of the realm of environmental acitivists and elevated to the mainstream. You might say it was a renaissance for the term ‘green’, but without the depth of expression. Most of the benefits of this green renaissance are felt today, but almost entirely in our electricity system, and not nearly as much as was promised. This is where ‘green’ as a term has fallen short. ‘Green’ was such a broadly used term for everything from packaging, to building materials, to accounting methods for carbon emissions, to the kinds of jobs people would be doing in a more sustainability focused economy. This broad, and increasingly ambiguous use of the term ‘green’ has become completely empty to its original purpose.

The term has evolved also into its evil twin, ‘greenwashing’. When something claims to be environmentally sustainable, but is no less polluting or sustainable than the alternative, and sometimes even less so. Even worse is that greenwashing can undermine the confidence of the public. So much so that it’s not just environmentally sustainable products that consumers lose confidence in, but also when they are voting, environmental and climate policy itself. It can lead people into a sense of nihilism that’s neither helpful for sustainability, nor the market.

Investment firms as well as fossil fuel companies are engaged in pretty high level greenwashing. When a company makes a grand announcement about bio-fuels, or a utility announces they are going net zero but has plans to build gas-fired power plants there’s usually a flashy PR campaign and little else in terms of reducing CO2 emissions. All this boils down to a truth that is much more nuanced than the label we’ve been using to communicate a move towards environmental sustainability. ‘Green’ as a label is losing its ‘stickiness’, and we can try to keep sticking it on, or find something that works better.

‘Green’ as a Wedge Issue

On the policy front green has a rocky reception, and usually for the wrong reasons. It’s common practice in politics to create so-called wedge issues to establish a ‘which side are you on’ policy debate, and ‘green’ is a very useful wedge issue for politicians. In a recent interview on the podcast Political Climate, Julian NoiseCat from the research firm Data for Progress recently said as much about the landmark climate change legislation, the Green New Deal, which he helped draft. He alludes to the fact that the Green New Deal was contentious from its inception, and partly because of this, gaining support for many of its measures in Congress may require a rebranding. Just recently, this ability of the term ‘green’ to polarize debate on climate solutions, and renewable energy was used to link progressive Green New Deal policies to renewable energy tax credits signed into law by President George W. Bush. It may not surprise anyone however, that former president Bush has never endorsed the Green New Deal.

Don’t Market ‘Green’, Market Value

It’s not easy being ‘green’. It’s an unwieldy phrase that has a dubious reputation. Worst of all, its primary value is to communicate the goodness of something with like minded individuals, and the badness of it with those opposed. Those in between are neither persuaded, nor dissuaded by the phrase.

This is a problem during the era of global climate change. Our transition to zero carbon emitting energy resources is not just something we need a niche group of individuals to engage in. We need more than a buzzword when we communicate about climate solutions. Moreover, we need to communicate that ‘green’ jobs, are jobs first and foremost.

So called green jobs comprise both white and blue collar jobs, but aren’t any different. No one calls fossil fuel jobs ‘black collar’ jobs. We do call green jobs ‘green collar jobs’ and the biggest problem with this phrase is it isn’t centered on the labor force, or labor rights and protections . It’s focused on the industry at large.

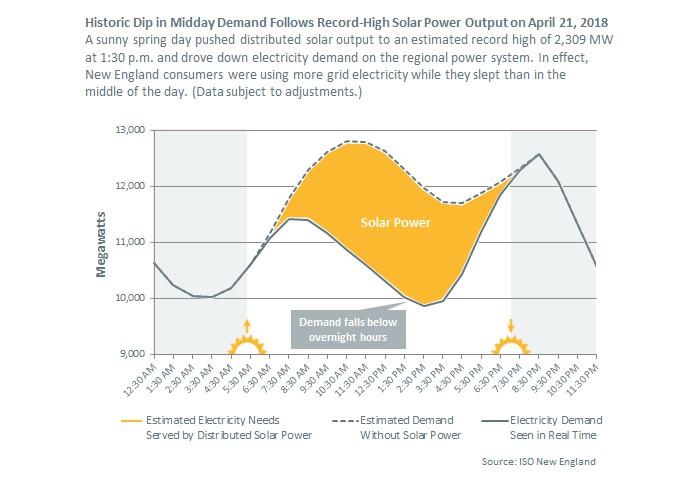

Regardless of the term ‘green collar job’, there’s also a perception that ‘green’ as a term is a marketing ploy, and that renewable energy is imbued with either magic when it works or bullshit when it doesn’t. I sold rooftop solar, and I know it’s not magic because I see the technology work. I see it work as a policy wonk when I see how much energy is generated by resources like solar and wind, in real time, in places that understand the value of these resources and provide policy that promotes it for the public good. I also know that when renewable energy doesn’t work it’s because of bad policy, and or bad actors in the industry. Like when regions don’t prioritize development of cost effective and less polluting renewable resources. Or when companies are run badly. My point is, it has nothing to do with the technology, or its excellent potential to eclipse other more polluting ways of making energy that we cannot continue to use. Many regions in the country that hardly focus on ‘green’ technology have prioritized it to an extent much greater than others.

The fact that a state like Texas is first in wind energy capacity and production in the entire country is not some indication that they’ve bought into ‘green’ energy. Where there’s an abundance of resources, there’s an abundance of energy to be harnessed. This is true of any technology. Energy is emotionally neutral, and politically agnostic, despite the efforts of businesses and politicians to make it so. It isn’t imbued with a magical power, whether it comes from a fracked gas well, a lump of coal, an atomic reaction, a solar cell, a spinning turbine or a battery. All technologies have different levels of usefulness in the physical world, and all of them have environmental impacts. The level of impacts on our climate are relevant though, and developing an economy that offers the lowest carbon resources possible in all of our consumer choices, including electricity, will lead meaningful action on curbing the effects of climate change. In that effort, we should ditch the word ‘green’, because in the just like any case of false advertising, it’s not actually making us greener at all.

18 May 2020

Medium