The global oil industry is experiencing a shock like no other in its history

The impacts will be felt throughout oil’s global supply chains and ripple into other parts of the energy sector.

The oil world has seen many shocks over the years, but none has hit the industry with quite the ferocity we are witnessing today

The oil world has seen many shocks over the years, but none has hit the industry with quite the ferocity we are witnessing today. As markets, companies and entire economies reel from the effects of the global crisis caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, oil prices have crumbled. The impacts will be felt throughout oil’s global supply chains and ripple into other parts of the energy sector.

Pressure is coming from all sides: a precipitous decline in global oil demand as the pandemic has slashed fuel consumption, especially in the transport sector, aggravated by a supply shock due to the end of restraints on production from OPEC producers and Russia (OPEC+). The scale of the collapse in oil demand, in particular, is well in excess of the oil industry’s capacity to adjust.

With 3 billion people around the world under some form of lockdown because of the coronavirus, one of the traditional stabilisers for the oil market is missing. Low prices usually stimulate a reaction from consumers, but such a boost to demand is highly unlikely this time around, at least for the duration of the global health emergency. Instead, a rapid build-up of oil stocks is starting to saturate available storage capacity, pushing down prices further.

This is an unprecedented moment for those engaged in the business of supplying oil and those who rely on the associated revenue. In this article, we highlight five key dimensions of this crisis – themes that the IEA is tracking in detail in our Oil Market Report (whose next edition is on 15 April), the Global Energy and CO2 Status Report (later in April), the World Energy Investment report (late May), and many other publications.

Some existing production will grind to a halt

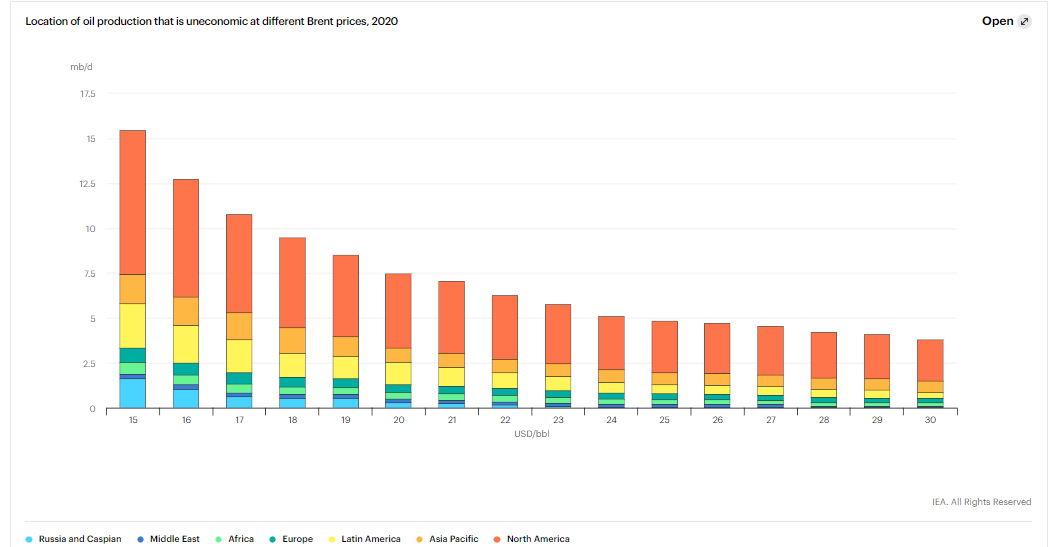

At the moment, about 5 million barrels of oil produced worldwide each day is not fetching high enough prices to cover the costs of getting it out of the ground (based on Brent crude at USD 25 a barrel, with variations to reflect the prices typically available to producers around the world). These operations are now losing money on every barrel they produce.

The economics of getting oil out of the ground are not necessarily a good guide to which operations will actually halt production. Depending on how long they think the crisis will last, some of the more robust producers may continue pumping oil even if they are losing money. This could happen if the costs of shutting down production (and eventually starting it up again, if that proves possible) are higher than the operating losses from keeping the oil flowing. Moreover, some producers may opt to wait and see if weaker rivals go out of business, which would improve the environment for those who stay in the game.

However, there is now an additional, even more pervasive threat facing many producers, irrespective of their operating costs or strategies. As demand plummets, the entire supply chain of oil refining, freight, and storage is starting to seize up, making it increasingly difficult to push new supply into the system. Prices available to producers have fallen to single digits in Western Canada and there have even been incidences of negative pricing for some grades in parts of North America. For some producers, there could soon be no place for their oil to go.

Sharp cuts in new investments will ricochet all along the supply chain

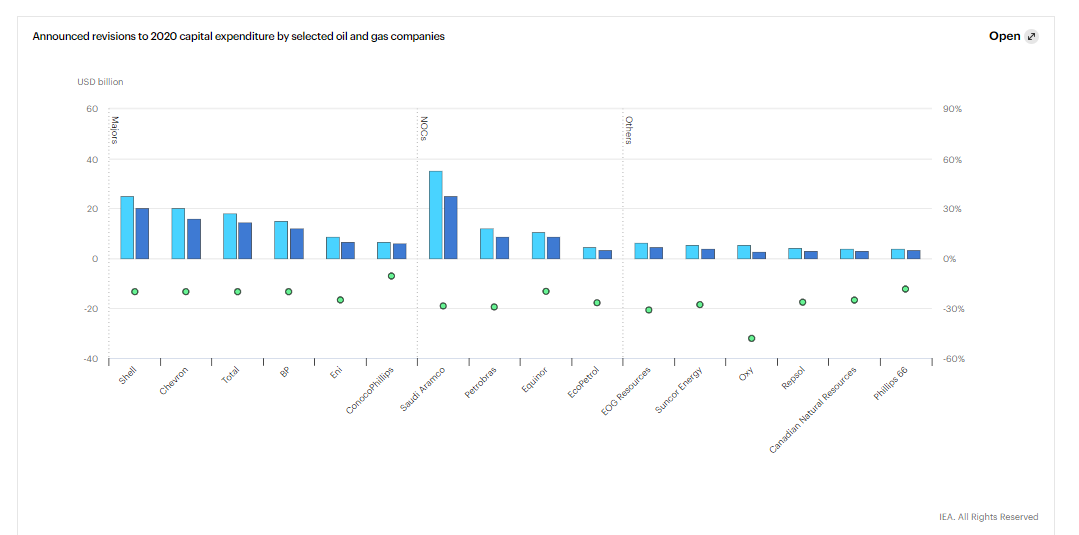

Oil companies have responded to the price collapse by announcing large cuts to their spending on new production. The initial reductions are in the 20%-to-35% range compared with investments they had previously outlined for 2020.

In the new environment, projects considered low cost yesterday (i.e. those that are viable at around USD 35 to USD 45 a barrel) already look high cost today, and only the most resilient investments have a chance of going ahead. Companies are pushing back other plans and redesigning them where possible in order to seek ways of driving costs even lower. Otherwise, they are shelving these projects entirely.

The scope for further cost reductions is much more limited today than it was after the last major drop in oil prices, in 2014-15, because much of the efficiency gains have already been harvested. As a result, the current declines in investment are translating more directly into cutting back activity.

These cutbacks are especially stark among some independent US companies and shale producers, many of which were already facing strong demands from investors to shore up business models and improve cash flow before the recent price crash.

Some producers have a modicum of protection because they hedged 2020 output at higher prices, but this respite rarely extends far into the future, and the design of some existing hedges are not providing much of a shield in these extreme market conditions.

All of this brings renewed hardship to companies that provide services and supplies to the oil industry: there have already been multiple announcements of layoffs.

Refiners are coming under huge pressure as well

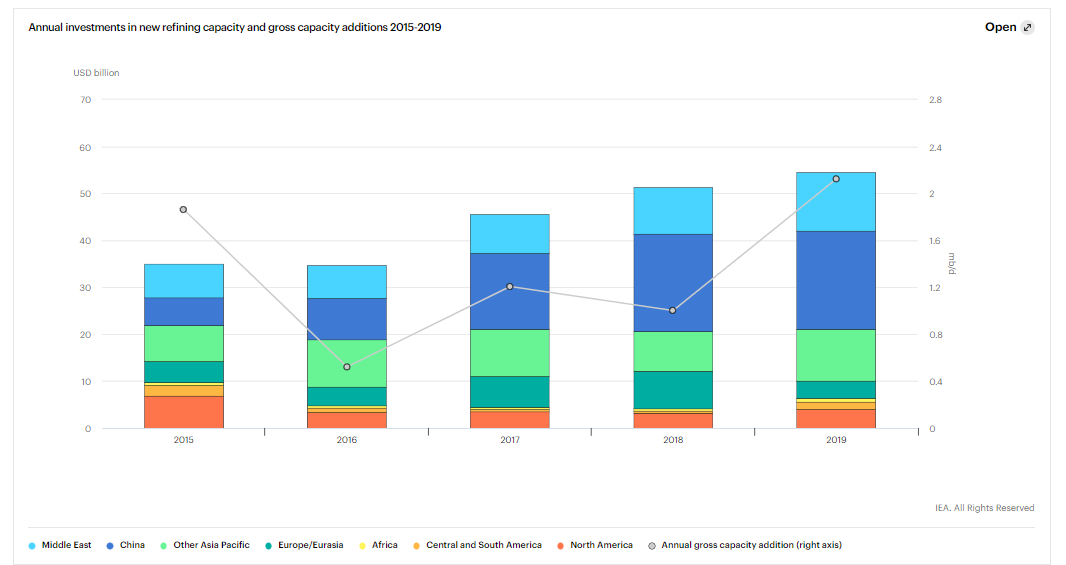

The last few years have seen a major ramp-up in investment in the refining sector and more than 2 million barrels a day of new refining capacity came on line in 2019 alone. Now, demand for oil products has collapsed, and the bottom has dropped out of the market.

In normal times, low crude oil prices are not necessarily bad news for refiners. However, the plunge in demand really squeezes refinery margins and volumes. This has dashed hopes among refiners of securing near-term benefits from changes in consumption, such as the anticipated boost in diesel demand arising from the new environmental regulations for the shipping industry from the International Maritime Organization.

Even before the enormity of today’s crisis had emerged, the IEA’s medium-term oil report, published in early March, was forecasting that net refining capacity would grow much faster than demand for refined products over the coming years. With demand now in freefall, the excess capacity now looms very large over the industry, posing an immediate threat to the outlook for older and more exposed operations.

Oil majors and independent refiners are already taking a hard look at planned investments and divestments. Many will re-evaluate their existing portfolios, possibly leading to another wave of refinery closures. This would accelerate the restructuring of the global refining industry towards regions benefitting either from cheaper inputs, such as the Middle East, or close to still-growing demand, such as in developing countries in Asia.

Massive strains on countries that rely heavily on hydrocarbon income

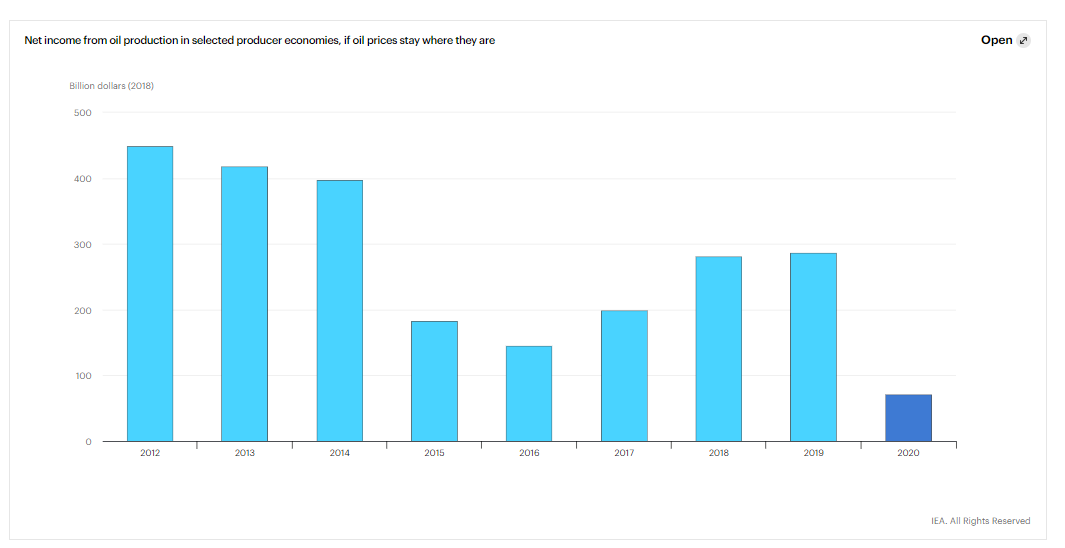

The IEA has already highlighted the risks posed by today’s market conditions for vulnerable producer economies. Our initial estimates of 50%-85% drops in net income for selected producer countries in 2020, compared with 2019, were dramatic. But these declines could be even greater depending on the final extent of the demand drop and the economic slowdown.

This would further undermine the ability of countries like Iraq and Nigeria to continue to pay salaries and provide essential services to their populations, such as healthcare and education.

Even among the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, some of which still have a degree of financial cushioning against worsening market conditions, fiscal deficits are now projected to reach 10%-12% of GDP this year, implying additional financing needs of around USD 150 billion to USD 170 billion.

The collapse in oil prices will spill over into other parts of the energy sector

Changes in oil markets ripple across all parts of the energy sector, with implications for a range of different fuels and technologies. A sustained period of low oil prices would affect the prospects for clean energy transitions, easing some aspects of this transformation – such as the removal of fossil fuel consumption subsidies – while complicating others.

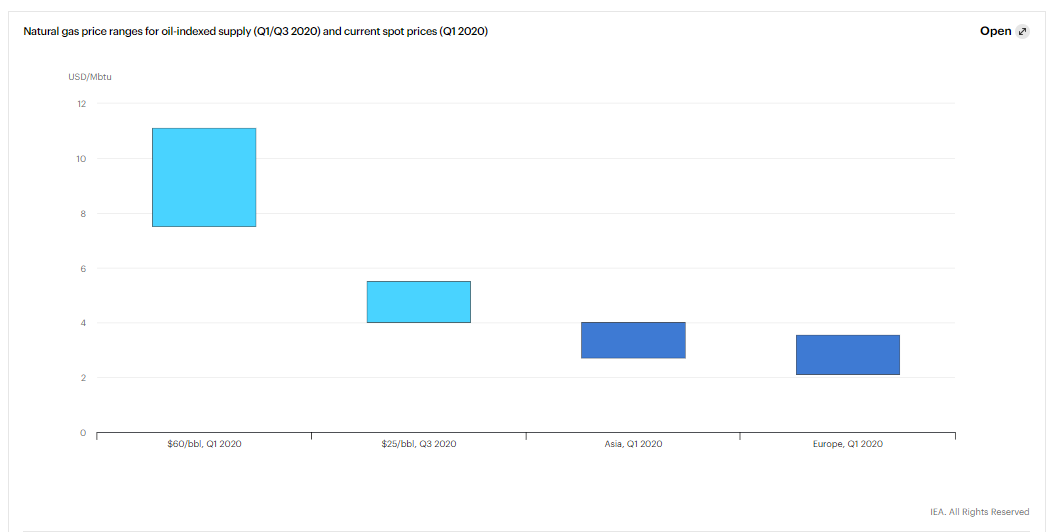

One of the clearest spillover effects is on natural gas because of the links between oil and gas prices that remain in many long-term gas supply contracts. This linkage had been offering a measure of shelter for some suppliers, but it is now set to disappear over the typical 6-9 month period in which movements in oil prices filter through into natural gas contract prices. The precise implications will vary from company to company. But oil at USD 25 a barrel would leave some international gas suppliers struggling to cover their operating costs, and the depressed spot market for gas would not provide any relief.

Gas demand is less exposed to the immediate effects of the current crisis than oil demand because of its relatively limited use for transport. But industrial and power demand for gas will still be affected by the lockdowns and the ensuing economic slowdown. With consumers constrained in their ability to respond to lower prices, adjustment in the gas market may also need to come in the form of halting some gas supply. Suppliers with the highest short-term costs of production and those who rely on spot sales are among the most vulnerable.

The oil industry’s worst crisis

Today’s crisis comes at a moment when the oil and gas companies were starting to grapple with the implications of energy transitions for their operations and business models. But some of the industry’s angst about the future has now been abruptly fast-forwarded to the present. Although demand for oil will rebound when the crisis eases, the dislocation could accelerate some structural changes in the way the world consumes oil. And the heavy cuts to investment in production capacity will definitely affect the medium-term prospects for oil supply. The IEA will continue to watch developments closely to assess implications for energy security and sustainability over the short term and the long-term.

The reverberations will extend beyond energy markets. Some oil-importing countries might experience benefits from low oil prices when their main focus shifts from dealing with their immediate health crises to the need to repair their economies. But the shock to some oil-exporting countries is going to be profound, bringing risks to their social stability and sharply curtailing their ability to buy essential goods and services from the rest of the world. The threat of bankruptcies in a sector with the size and strategic importance of oil, alongside the crucial role of oil in global finance and trade, add hazardous elements to a highly unstable global financial situation.

Comparisons with previous periods of disruption in oil markets are inevitable but misplaced. The oil industry has never seen anything like 2020.

*Read the original article here

1 April 2020

iea