Germany’s Bet on Solar Power May Get Lost in the Wind.

As Germany prepares to pass its climate protection plan through 2030, the government is trying to decide whether to prioritize solar or wind energy. The latest version of the plan leans toward solar, and that makes economic sense, but it also represents something of an unwelcome turnabout for the existing renewables industry, which is mostly wind-focused.

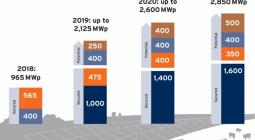

In the most recent version of the program, the 2030 target for installed wind power capacity has been lowered, while the target for solar has been substantially increased.

Betting on the Sun

The latest draft of the German climate protection program envisages a bigger increase in solar than in wind capacity

That irritated the German wind industry lobby, BWE, which issued an angry statement saying the planned increases in wind capacity were “neither a basis for securing the depth of value added in the German mechanical engineering sector, which has been hard-earned over the past 30 years, nor a sufficient foundation for securing the international competitiveness of German companies.”

The wind lobby has a point.

Until recently, Germany prioritized wind for two main reasons: Most of the country is not known for an abundance of sunshine, and energy companies don’t have to change their business models as much for large wind farms as for a multitude of smaller solar installations.

As a result, Germany has built up quite a position in wind. Last year, according to BloombergNEF, it generated about 17% of its energy from wind and only 7% from solar. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, Germany accounted for 29% of global technology and equipment exports in wind and just 5% in solar. And last year, the wind industry employed almost 141,000 people in Germany, compared with fewer than 30,000 for the solar industry.

However, the government experts pushing for less wind and more solar have a point, too. According to a 2018 study by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, the cost of generating solar energy will go down faster over the next 17 years than the cost of wind energy. By 2035, photovoltaic installations in southern Germany, where there’s more sunlight, will be producing significantly cheaper power than any other kind of plant; and even in less sunny northern Germany, solar energy produced by industrial-sized installations will be about as cheap as onshore wind.

That prediction follows the current trend. The global average cost of producing solar energy went down by 77% between 2010 and 2018, compared with a 35% decrease for onshore wind.

Technological advances are the reason for the reduction in solar energy cost. The decline in solar panel prices has slowed down recently, but in the long run, the potential market, and thus the potential economies of scale, look bigger for solar than for wind. One could put a solar panel on every roof if it’s cheap enough, but wind turbines require much more space (which makes them a target for “not in my backyard” resistance, a significant political factor in Germany).

The government, therefore, is trying to plan in line with the trend. A mix of solar and wind is necessary to ensure a stable energy supply (in Germany, sunlight and wind strength are negatively correlated), but solar appears to have more potential when it comes to cutting emissions in the next decade or so.

The problem with such planning, of course, is that technological progress is hard to predict – and that a government’s goal-setting can interfere with it. If a certain technology becomes the priority, alternatives will get less government funding and less private investment, and cost-reducing breakthroughs will become less likely. While renewable energy is still highly dependent on government policy, Germany and other countries must be sensitive to maintaining a balance between competing technologies. Clearly prioritizing one over another may lead to a country’s ending up with a less efficient energy mix than it would like.

10 October 2019

Bloomberg Opinion