German Failure on the Road to a Renewable Future.

In 2011, German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced the country was turning away from nuclear energy in favor of a renewable future. Since then, however, progress has been limited. Berlin has wasted billions of euros and resistance is mounting.

It's a fantastic idea. The energy landscape of tomorrow. There are 675 people in Germany working every day to make it a reality -- in federal ministries and their agencies, on boards and panels, in committees and subcommittees. They are working on creating a world that on one single day in April became glorious reality. Here in Germany. It was April 22. Easter Monday.

That day, it was sunny from morning to evening and there was plenty of wind to drive the turbines across the entire country. By the time the sun went down -- without the need of even a single puff of greenhouse gases -- 56 gigawatts of renewable energy had been produced, almost enough to cover the energy needs of the world's fourth-largest industrialized nation.

Unfortunately, it was only for that day.

The other days are dirty and gray: Most of the electricity that Germany needs is still produced by burning coal. Then there are the millions of oil and natural gas furnaces in German basements and the streets packed with the cars with diesel- and gasoline-powered motors.

The vision of the fantastic new world of the future was born eight years ago, on March 11, 2011, the day an earthquake-triggered tsunami damaged the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Japan. The disaster led Chancellor Angela Merkel and her cabinet to resolve to phase out nuclear power in Germany. It was an historic event and an historic decision.

But the sweeping idea has become bogged down in the details of German reality. The so-called Energiewende, the shift away from nuclear in favor of renewables, the greatest political project undertaken here since Germany's reunification, is facing failure. In the eight years since Fukushima, none of Germany's leaders in Berlin have fully thrown themselves into the project, not least the chancellor. Lawmakers have introduced laws, decrees and guidelines, but there is nobody to coordinate the Energiewende, much less speed it up. And all of them are terrified of resistancefrom the voters, whenever a wind turbine needs to be erected or a new high-voltage transmission line needs to be laid out.

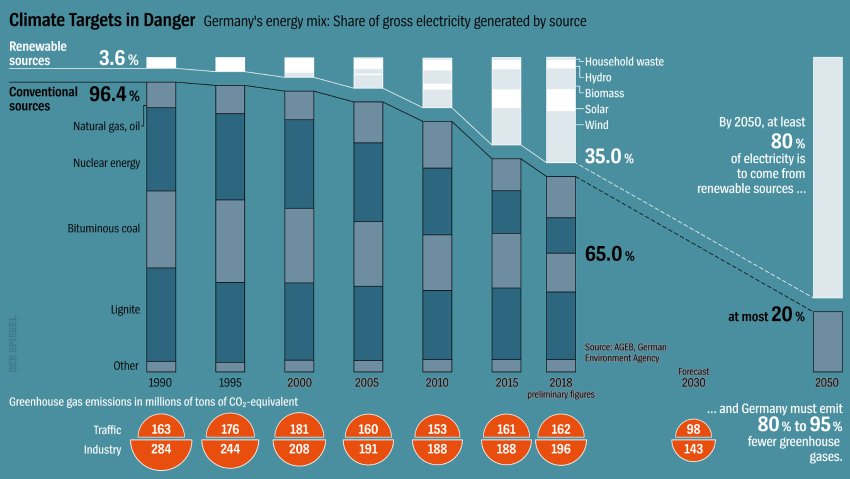

Analysts from McKinsey have been following the Energiewende since 2012, and their latest report is damning. Germany, it says, "is far from meeting the targets it set for itself."

Germany's Federal Court of Auditors is even more forthright about the failures. The shift to renewables, the federal auditors say, has cost at least 160 billion euros in the last five years. Meanwhile, the expenditures "are in extreme disproportion to the results," Federal Court of Auditors President Kay Scheller said last fall, although his assessment went largely unheard in the political arena. Scheller is even concerned that voters could soon lose all faith in the government because of this massive failure.

Surveys document the transformation of this grand idea into an even grander frustration. Despite being hugely accepting initially, Germans now see it as being too expensive, too chaotic and too unfair.

How Germans Will Live and Work

And yet, the future of the entire country depends on it: ecologically, economically and technologically. But also societally. In contrast to the new Berlin airport, whose opening has been delayed for years, the Energiewende cannot just be shrugged off as a regional blunder. It is a project that will determine how Germans will live and work in the future, how German industry will remain competitive and what societal cooperation will look like.

Politicians are quick to label projects as being in the national interest, but this one truly is -- especially given that environmental leadership has become a key element of German identity. A majority of Germans were once proud of the turn away from nuclear and toward renewables, a pride political leaders could have capitalized on.

But the grand transformation has lost its way. The expansion of wind parks and solar facilities isn't moving forward. There is a lack of grids and electricity storage -- but for the most part there is a lack of political will and effective management. The German government has dropped the ball.

In the Economics Ministry alone, 287 officials are working on the issue, divided into four divisions and 34 departments. There are at least 45 additional bodies at the federal and state levels, full of people who also want to move the project forward. They collect vast quantities of data and come up with complicated incentives -- a huge effort that has produced only modest results.

One example is STEP up!, an incentive program meant to help companies deal more efficiently with electricity. Its initial goal was to approve 1,000 applications in 2017, but only seven were authorized in the first three quarters of that year. Then there is the law providing tax incentives for electric vehicles. Six months elapsed between the drafting of the law and its publication, despite the legislation's status being "particularly urgent."

Experts are getting bogged down in details -- producing papers, but no strategies. For months, the vital position of state secretary for energy remained vacant. Nobody feels a sense of responsibility and there is nobody to decide what tasks have priority. Because Germany doesn't even have an Energy Ministry, the issue ends up falling through the cracks. And the chancellor has not stepped in to point the way.

In December 2015, Merkel signed the Paris Agreement on climate change, in which Germany pledged to do its part to slow global warming. More than three years have passed and almost nothing has been done. The migration debate and the rise of the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany have largely shunted the issue of climate change.

At the 2007 G-8 Summit in Heiligendamm, in northern Germany, Merkel indicated she was sympathetic to the idea that every person on earth should be allowed to emit the same amount of CO2. It was a revolutionary idea. But nothing came of it.

'Biggest Hurdle'

Even earlier, in 1997, back when she was the German environment minister, Merkel told DER SPIEGEL: "When it comes to reducing CO2 emissions, vehicle traffic is the biggest hurdle." She could say the same thing today.

With Merkel's tenure as German chancellor now coming to an end, her greatest failure would seem to be that she has done so little to advance climate policy, despite it having been a key issue for her early in her political career. Even though Germany introduced the term Energiewende to the global vocabulary, much like kindergarten or wanderlust, its successful implementation has been left to others.

Like the Netherlands, for example, which has long been the largest supplier of natural gas to the European Union. The country has decided to completely abandon the production of the fossil fuel within a decade and to use the pipeline infrastructure for gas produced from wind power with the help of power-to-gas, or P2G, technology. In six years, no more cars with internal combustion engines will be licensed.

In Sweden -- the Energiewende world champion, according to the International Energy Agency -- a high CO2 tax, of almost 120 euros per ton, is driving people and companies to pay more attention to how they heat, drive and do business. The tax was first introduced there in 1991. In Germany, the debate has only just begun.

Even the U.S. is making improvements. Americans are increasingly turning from coal to natural gas to generate electricity. It's only slightly less dirty, but the country's CO2 emissions are trending in the right direction.

Progress, in other words, is being made everywhere -- just not in the birthplace of the Energiewende. German CO2 emissions have only slightly decreased this decade. Eberhard Umbach is on the board of directors at a scientific initiative called Energy Systems of the Future (ESYS). He says that the view of the Energiewende has shifted. Just a few years ago, he says his foreign counterparts were skeptical but also full of admiration for the élan with which Germany had jumped into the project. And now? "It has completely reversed," the scientist said at a February conference. "Others are faster than we are."

The transformation that has already taken place -- the shift in electricity production, fueled by billions in expenditures -- was the easiest step in the process. Politicians have ignored other elements, like industrial production, building efficiency and, especially, vehicle traffic. Involving those areas and coming up with an overarching concept, that's the hard part that must now be addressed. And it will determine whether Germany will once again become a model of sustainable economic production or whether the entire experiment will end in failure.

So, how did this marvelous idea turn into such a monumental failure?

Why Germany's Energiewende Might Fail

The German government made a key mistake when it announced the end of the nuclear era in Germany eight years ago: It announced it was turning away from nuclear power, without simultaneously initiating the end of coal.

Wind turbines and solar panels were installed across the country -- but the coal-fired power plants kept operating. The government set up a clean energy system alongside the dirty one. But why? Because Berlin was afraid of do anything that might harm a single company or voter.

Germany has never come up with a clear strategy for the shift to renewables, fully thought out from the beginning to end. There have always been two competing concepts of the Energiewende, even before Merkel.

Politicians like former Environment Minister Jürgen Trittin, a Green Party politician who was part of the cabinet of the center-left Social Democratic (SPD) Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, were in favor of a radical shift, no matter what the cost. Others, like the SPD Economics Minister Sigmar Gabriel and his successor Peter Altmaier, from Merkel's center-right Christian Democrats (CDU), were more concerned about German industry and job numbers. Neither side trusted the other and a stalemate ensued. Progress halted.

This helps explain why the government never dared set up an Energy Ministry that might have had the ability to move things forward, and instead divided up the project among the Chancellery, the Environment Ministry and the Economics Ministry. It is an unholy trinity that has continually followed the same pattern: The Environment Ministry surges ahead, the Economics Ministry warns of dramatic job losses and the Chancellery avoids making a decision.

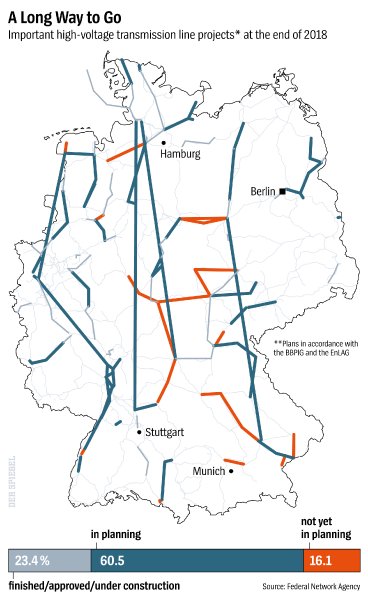

The expansion of Germany's electrical grid has suffered the most from this lack of political impetus. More than a decade ago, the German government passed a resolution to quickly build the necessary high-voltage transmission lines, with experts today saying there is a need for 7,700 kilometers (4,800 miles) of such lines. But only 950 have been built. And in 2017, only 30 kilometers of lines were built across the whole country.

In Berlin, one can hear the wry observation that 30 kilometers is roughly the distance that a snail can travel in a year.

Instead of explaining to voters why it is necessary to conduct such a grid to bring energy from the windy north to the industrially strong south, politicians have wilted in the face of NIMBY protests. Indeed, almost everywhere such a power line tower or wind turbine is to be erected, officials are met with protest. Politicians have thus decided to put most of it underground, which is vastly more expensive and will take years longer to build.

Nine years ago, Rainer Spies, the mayor of the municipality of Reinsfeld in southwestern Germany, began planning the construction of a wind park. Together with the power company EnBW, he wanted to erect 15 turbines in a small forest not far from the highway between Trier and Saarbrücken. "Everything seemed to be ready," Spies says. But then the permit process began.

A Red Kite

The mayor and EnBW submitted the requisite documentation -- several hundred pages and a number of environmental studies. But the authorities continually demanded more: species protection analyses, bird flight patterns, noise emissions, shadow patterns and, not least, potential dangers posed to the barbastelle bat, along with detailed information pertaining to its local population. Finally, after the fourth application, officials approved the wind park's construction last year.

The local municipality should have issued a construction permit soon thereafter. But then, someone discovered the nest of a red kite in a fir tree just a few hundred meters away from the planned wind park. It was the worst thing that could possibly happen.

The bird of prey, with its elegantly forked tail, enjoys strict protection in Germany. It eats mice and moles and its enemies include owls and pine martens -- and wind turbines. The birds like to hunt in the cleared areas beneath the turbines because it is easy to spot their prey.

Red kites are migratory, returning from the south in the spring, but they don't return reliably every year. The mayor would have been happy if the bird had shown up quickly so its flight patterns could be analyzed and plans for the wind park adjusted accordingly. It would have been expensive, but at least construction of the project could finally get underway.

But if the bird doesn't return, the project must be suspended. Spies has to wait a minimum of five years to see if the creature has plans for the nest after all. Which means the wind park could finally be build in 2024, fully 12 years after the project got underway.

The situation in Reinsfeld is, of course, an extreme example, but it provides an important explanation for why Germany has fallen behind in the transition to renewables. Plans for new wind parks regularly trigger conflict with officials and, especially, with neighbors. There is hardly a new project these days that doesn't find itself confronted with dissent, or even lawsuits.

It used to be that 40 months would pass between the signing of a land-use contract and a facility going into operation. Today it takes 60 months. At least.

Badly Needed Reforms

The degree to which this has depressed investment can be seen at the auctions held by the Federal Network Agency to sell licenses for wind park construction. These days, there are fewer people taking part in the auctions than there are commissions available -- which means there is no longer any competition. "The entire system is a bit out of kilter," says EnBW head Frank Mastiaux. "Reforms are badly needed."

The number of new construction projects has collapsed in Germany, with just 743 new wind turbines joining the grid last year, 1,000 fewer than in the previous year. In Bavaria, Germany's largest state, just eight went into operation. The wind power boom is over, and manufacturers are suffering. Enercon and Nordex are slashing hundreds of jobs while Senvion, known as Repower Systems until 2014, has filed for bankruptcy. The industry is concerned that it could be facing a debacle of the kind that has already befallen German solar.

Germany is also falling short of its initial targets when it comes to the expansion of offshore wind parks. In the North Sea and Baltic Sea combined last year, the extra capacity that went online didn't even add up to one gigawatt -- 23 percent lower than the previous year. In mid-April, Merkel inaugurated the Arkona wind park off the coast of the Baltic Sea island of Rügen. But not even the charming images of people blowing into their toy windmills at the ceremony can hide the fact that not even offshore wind parks are a growth market anymore.

It is a systemic problem: Wind park operation and grid connection are not in the same hands, in contrast to places like Britain, for example. Coordination can be difficult, costs are high and potential goes unused. It is hardly surprising that nobody wants to generate electricity on the high seas if it isn't guaranteed that it can get to where it needs to go because the grid to southern Germany doesn't exist.

Even connecting a normal solar park to the grid can test one's patience. In Spain, grid connection is guaranteed when the construction permit is issued. In Germany, though, it is "often an incalculable risk," says Dierk Paskert, head of Encavis, the largest independent operator of solar parks in Germany. Even if grid operators play along, it is often the case that the planning authority, municipalities or even individual citizens stand in the way. "It makes planning difficult," says Paskert.

13 May 2019

SPIEGEL ONLINE