ExxonMobil says the long-term fundamentals have not changed. Really?

No fundamental shift is taking place in global energy markets, according to company reports

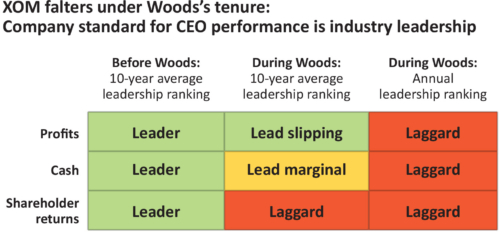

In April, when announcing its first-quarter financial performance, including its first quarterly loss in decades, CEO Darren Woods, said: “The long-term fundamentals that drive our business have not changed.” In July, when it announced its even more dismal second-quarter financial results, management confirmed its view that “the fundamentals have not changed.” The market sees it differently. The company’s stock price is in the $30/share range. In 2014, it was more than $100. Its market capitalization is less than $150 billion. It once was $527 billion.

Market observers know this has almost nothing to do with the coronavirus pandemic. They’ve watched the company’s annual revenues decline from a peak of $486 billion to the current $200 billion range. They’ve noted the company’s long-term debt has ballooned from less than $10 billion to $40 billion, much of it incurred recently to pay its unsustainable dividends.

To support its nothing-has-changed scenario, Exxon notes: “The population will continue to grow. Economies will continue to grow.” These significant demographic realities and resulting demand for energy are proof-positive that demand for hydrocarbons will accelerate, rising 25% by 2040. And, according to Exxon, the “winner will be the company with the strongest portfolio and the company with the strongest operating results.”

Let’s run a diagnostic on the assumption that nothing fundamentally has changed:

Exxon assumes that growing populations and economies will increase energy demand. If this assumption is correct, is ExxonMobil positioned to take advantage of this growth? Given withering revenues, bloated debt levels and eviscerated asset values, and the financial position of ExxonMobil, absolutely and relative to its peers over the last 10 years, the clear answer is no.

Exxon assumes historical growth patterns of GDP require it to increase its oil and gas reserves annually. But can Exxon maintain this business-as-usual practice? Based on drastic cuts in its annual capital expenditures (capex) budgets and its aggressive plans to divest assets, the clear answer is no.

But clearly, something fundamental has changed. It is happening now:

- The small market share of electric vehicles will crimp growth assumptions for ground transport, despite the slow uptake of electric vehicles that remains a source of comfort to the fossil fuel industry.

- Growth in the U.S. domestic market for natural gas has stalled. IHS Markit, a leading oil and gas industry consultant, forecasts that renewable energy will be the investment choice of the nation’s utilities after the pandemic, despite low natural gas prices. Natural gas as a heat source faces both market and policy challenges, based on recent pipeline cancellations. According to Moody’s, new pipeline capacity is now a dubious credit proposition.

- LNG exports, once viewed as the solution to domestic natural gas oversupply, face stiff global competition from suppliers in Russia, Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

- Petrochemical growth is unlikely to significantly outpace gross domestic product (GDP) growth at levels forecast by Exxon—petrochemical growth of 5% compared to normal GDP. Other business analysts see recycling driving down polyethylene demand to a level where virgin plastics growth is only 1% annually.

The market is forward-looking and has severely punished the oil and gas sector over the past 10 years in the wake of the cumulative impact of these competitive drivers. The once cash-rich company now needs a sharp, extended upswing in oil prices lest it run through its asset base chasing after the ghost of profits past.

Is the oil and gas sector destined to follow coal? Though there is little comparison between the coal industry’s demise and the current predicament of the oil and gas sector, ExxonMobil’s current mantra—no fundamental change—echoes that of many coal mining companies just a few years ago. When former U.S. President Barack Obama announced a coal lease moratorium to update an outdated program that had not been studied in more than 30 years, he was met with cries from the coal industry: The coal lease program and the markets were working just fine, and there was no need for such action.

The moratorium took place during a long line of coal company bankruptcies. The coal industry was rapidly losing market share to cheap natural gas and a growing renewable energy sector. When the coal lease moratorium was lifted by the Trump administration, the bankruptcies continued. The parade of coal bankruptcies and disappearing coal companies continues to this day, with some facing a second bankruptcy after a few short years.

The long-term decline of the coal industry started long before Obama’s 2016 moratorium. At the time, some of the coal sector’s best friends said the “dumb money” was in coal.

Where is the “dumb money” invested now? The market collapse of ExxonMobil’s stock, its fall from the vaunted Top-10 list of the Standard & Poor’s 500 last year and its recent ejection from the Dow Jones Industrial Average might provide clues. All of this points to fundamental change.

Now, there is fundamental change needed at the top of ExxonMobil.

20 October 2020

IEEFA