The cow in the room: why is no one talking about farming at Cop26?

Sustainable food systems are a cornerstone to cutting emissions but have been largely absent from the agenda in Glasgow

“The cow in the room is being ignored at this Cop,” says Carl Le Blanc of Climate Healers. “Animal agriculture has been taken off the agenda and put on the menu.”

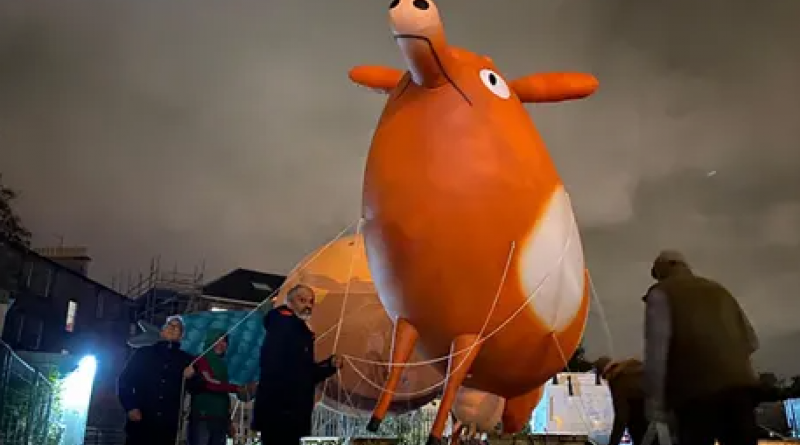

Le Blanc was one of a number of campaigners who joined climate marches on Saturday in Glasgow to demand action for a new sustainable food system. They fought strong gales to make their point with four giant inflatable animals tethered on ropes above their heads or strapped to the ground. Each symbolised a different problem of the livestock industry: a 40ft cow for methane, a chicken for Covid and health, a fish for microplastics, and a pig for obesity.

Many industry representatives and campaigners feel not enough attention has been paid to food and farming at Cop26, despite it being one of the keys to cutting emissions over the next few decades. Food served at the canteen has been criticised – nearly 60% of dishes contain meat or dairy, which campaign group Animal Rebellion described as the equivalent of “serving cigarettes at a lung cancer conference”.

During the two weeks of the conference, themes such as finance, energy and transport have been allocated their own days, but there has been no dedicated day for agriculture or food systems. Farming was included in Nature day on Saturday, where there was a lot of talk about protecting forests but less about cutting meat consumption, food waste and firm pledges to change farming subsidy systems.

Farming is a complex issue on the journey to net zero, as it is both a source and sink for emissions. About 20% of global emissions come from agriculture and land use, and this rises to more than 25% for the food system as a whole, which includes processing, packaging and transport. Yet huge amounts of carbon can be sequestered by modifying farmland, with the creation of more forests, healthier peatlands and wetlands. Although some argue that we should stop consuming animal livestock altogether, others believe that low densities of grazing animals such as cattle are an important part of creating farmland habitats that produce food and also provide a home for wildlife.

In terms of individual action, moving to a more plant-based diet is one of the single most effective ways to reduce emissions, but the UK government appears to be unwilling to put the science on this issue into policy. It quickly deleted research alongside its net zero strategy that encouraged levies on high-carbon foods, such as meat.

None of the presidents of the UK’s four farming unions present at Cop26 believe they should reduce livestock numbers in their respective countries, or that people need to reduce their meat consumption. They told the Guardian methane emissions could be dealt with through new technologies rather than reducing the number of cows on farms. Thomas Vilsack, the US secretary of agriculture says he believes Americans can carry on eating the same amount of meat while keeping the world within safe limits on global heating.

In a small side room at the Cop26 conference, pro-vegan groups said there was more discussion of meat than at the Cop two years ago, but still policy lagged far behind science. “Animal meat is obsolete, it doesn’t make any sense. It’s from the last century,” says Bernat Añaños, co-founder of plant-based meat company Heura Foods.

But others warn it is dangerous to reproduce historical tendencies to tell farmers what their goals should be. “There cannot be a one size fits all,” says Ishmael Sunga, CEO of the Southern African Confederation of Agricultural Unions (SACAU). “I respect that space, but they cannot impose their views on others.”

Small family farms produce a third of the world’s food, and hundreds of millions of people depend on livestock farming for their livelihoods. Although farming for animal proteins is a key driver of biodiversity loss, Sunga says it is important to make sure any changes are fair for producers on the front line. “It needs to be a just transition. We know most of the farmers in developing countries are near-destitute. It’s also an irony that food is one of the biggest industries in the world, but it delivers so badly for farmers. They go hungry, they absorb the climate front-risk, while the rest of us carry on walking around smiling.”

The only significant agricultural announcement made on farming at the leaders’ summit was the AIM4C declaration unveiled by the US president, Joe Biden, in partnership with the UAE. It promised an extra $4bn for agricultural innovation aimed at reducing emissions. But this has been criticised by many activists who say it is an attempt to reframe destructive intensive farming as part of the climate solution, instead of the problem.

“The US and the UAE are presenting a vision for the future of farming that is a future without farmers. Such a form of agriculture is a dangerous fantasy,” says Tom Wakeford, an ecologist and action researcher at ETC Group.

There are two main camps when it comes to agriculture’s relationship with wildlife. Some believe in land sparing, which is essentially farming intensively with separate areas for wildlife, while others believe in land sharing, which refers to agroecological approaches where farming and wildlife co-exist.

Jyoti Fernandes, a Dorset farmer and policy and campaigns coordinator at the Landworkers’ Alliance, is a proponent of the latter. She believes livestock is an important part of traditional land management. For her, the key is to stop intensive meat farming and focus on producing high-quality meat within smaller, mixed farms that provide high employment for local people.

“It’s outrageous that so little time at Cop26 has been devoted to agroecological farmers,” she says. “The programme is very weak. If they are promoting nature we must talk about farming. Agroecological farming can nurture biodiversity, sequester carbon and regenerate the planet by looking after our soil, creating habitat and planting trees.”

Subsidies are at the heart of how agricultural landscapes have been shaped. A recent UN report concluded that almost 90% of the $540bn of global agricultural subsidies given to farmers destroy nature and fuel the climate crisis. Subsidies have generally encouraged farmers to produce as much food as possible, but this has been at the expense of wildlife.

With habitat destruction due to the expansion of farmland identified as one of the main drivers of biodiversity decline, many are arguing for farming subsidies to be radically overhauled. The UN report found redirecting subsidies to beneficial farming practices could be a “game changer”, yet there was little mention of them in the leaders’ speeches at Cop26.

The most significant announcement came on Nature day, when governments endorsed the Policy Action Agenda, signalling their intent to shift agricultural subsidies to better support climate and nature-friendly farming. Although it only involved 16 countries, it included large emitters, such as Switzerland, Nigeria, Spain and UAE; in total these countries represent 10% of world’s greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. The UK also launched a £65m Just Rural Transition programme to help developing countries move towards more sustainable agricultural systems.

The UK farming policy Environmental Land Managements (ELMs), announced earlier this year, will reward farmers for delivering public goods, such as tree-planting, water retention and biodiversity benefits on their farms. Farmers grazing livestock less intensively, with more space for nature on their farms, will also be rewarded.

England’s National Farmers Union president, Minette Batters, says changing the subsidy system and harnessing private funds is an opportunity to implement nature-based solutions such as planting trees, using less chemical fertilisers, creating more hedges and enriching soils on farmland.

“We’ve got the opportunity to create a new relationship with the land, and new economic value for the land. We all talk about it, but we’re absolutely appalling at delivering the finance back into where it needs to go. Those trillions just circulate in the ether. We’ve got to drive that financial resource back into the soil.

“We can’t do anything without farmers, they are the eco-workforce of the future,” she says.

While many industries like coal and gas might have felt positive about not being included in the Cop26 programme, many farmers feel they can make a real difference.

“What is baffling for us, is why farming is not on the table with negotiators,” says Sunga. “By focusing on other areas and not focusing on food and agriculture you are running away from the problem, and that’s where solutions with the greatest impact are going to be.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features

9 November 2021

The Guardian