Climate protesters won’t be deterred by fines, jail or political mixed messages on the environment

Activists are convinced a wartime campaign of resistance is the only way to highlight the existing system’s failure to meet the moment

As pro-Palestinian protesters sparked outrage scaling the roof of Parliament House last week, a few dozen activists at Newcastle were making an equally sharp point – mostly to less fanfare.

Over more than two weeks, campaigners under the Blockade Australia banner have been interrupting trains near the world’s biggest coal port. My colleague Jordyn Beazley reported that by Monday at least 500 train journeys had been cancelled and more than 30 people arrested.

Laura Davy, a 21-year-old Tasmanian who was one of several who travelled to protest, was sentenced to three months jail for entering and causing serious disruption at a major facility. Without the benefit of being in court, it seems a disproportionate sentence for an act of political protest. Others have been fined $750 to $1,500. Davy was released on bail on Tuesday after their sentence was appealed.

These campaigners are at the frontline of a direct action movement that has been building steadily across the country. Last November it brought hundreds of people to Newcastle to paddle out in kayaks and other watercraft to stop ships coming and going through the port. Then, more than a hundred people were arrested. A similar event is planned later this year.

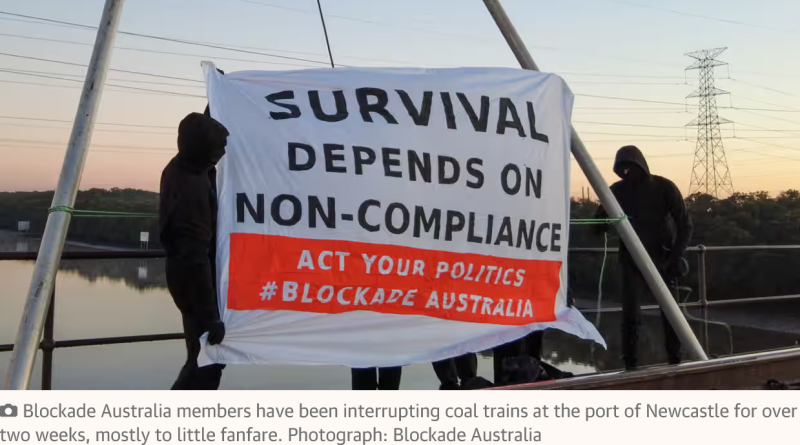

The worldview of these protesters was summarised in a banner that Ian Fox, a 67-year-old Adelaidean, unfurled while dangling 10 metres above a Newcastle rail line. It read: “Survival depends on non-compliance.”

It was a similar story on Sydney Harbour on Sunday, when protesters from the group Rising Tide paddled across to Kirribilli with a gift for the prime minister: a scroll signed by hundreds of people promising civil disobedience in response to what they see as an absolute failure to rise to the challenge of climate change.

Craig Foster, the Socceroo turned human rights activist, had earlier told a Rising Tide event that Australians should engage in direct action to take on the power of the coal and gas industries.

These are not new ideas. They have been echoed across the country in protests in Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania. Organisers say the number of people willing to sign up is growing.

Many words have been spent debating whether this is a good way to galvanise support for more rapid action on the climate crisis. You can mount a pretty compelling argument that it isn’t. But from the perspective of the people clambering across coal trains this misses the point.

They argue the failure to address the climate crisis is evidence the political and economic system is fundamentally broken and the only logical response is a campaign of resistance. They say the incrementalism of big environment organisations doesn’t cut it while new fossil fuel developments are being approved and significant parts of the world have just sweltered through what was the 13th-straight hottest month on record.

As one activist put it to the Guardian, the attitude is: “Fuck it, I’m going to do something about it.”

You don’t have to consider this for long to realise that the way state governments have responded – increasing fines and jail times – isn’t going to do much to deter the blockades.

Governments have nothing to offer these protesters. On a national scale, the Albanese government points to steps taken since it was elected two years ago: an expanded clean energy underwriting program as it aims for 82% renewables by 2030, vehicle emission standards that should gradually turn over the national fleet to cleaner models, a deal with the Greens that should initially cap emissions from industrial polluting sites, the creation of offshore windfarm zones, a Net Zero Economy Authority to help fossil fuel communities through the transition.

Some of these could lead to significant change. But Labor undermines its message when it uses flawed environmental laws to approve new fossil fuel developments and releases a gas strategy 2050 that reads as though it was written by the gas industry. It sabotages its message when a cabinet minister poses for happy snaps with the boss of a fossil fuel company that is seeking approval for a massive expansion in export production.

It is possible this complicated mix of messages could yet become a more coherent path to a clean economy. A net zero plan is promised before the election.

But it is near impossible to imagine it will be enough to win over climate protesters who are not interested in a promise to reach net zero in 26 years’ time, who are armed with scientific evidence that the current response isn’t coming close to meeting the moment and willing to dedicate their lives to making that point.

Which tells us that, like it or not, climate-focused civil disobedience is not going away. It might be time to listen up a little more and rethink our collective response to it.