1% of people cause half of global aviation emissions – study.

Exclusive: Researchers say Covid-19 hiatus is moment to tackle elite ‘super emitters’

Frequent-flying “‘super emitters” who represent just 1% of the world’s population caused half of aviation’s carbon emissions in 2018, according to a study.

Airlines produced a billion tonnes of CO2 and benefited from a $100bn (£75bn) subsidy by not paying for the climate damage they caused, the researchers estimated. The analysis draws together data to give the clearest global picture of the impact of frequent fliers.

Only 11% of the world’s population took a flight in 2018 and 4% flew abroad. US air passengers have by far the biggest carbon footprint among rich countries. Its aviation emissions are bigger than the next 10 countries combined, including the UK, Japan, Germany and Australia, the study reports.

The researchers said the study showed that an elite group enjoying frequent flights had a big impact on the climate crisis that affected everyone.

They said the 50% drop in passenger numbers in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic should be an opportunity to make the aviation industry fairer and more sustainable. This could be done by putting green conditions on the huge bailouts governments were giving the industry, as had happened in France.

Global aviation’s contribution to the climate crisis was growing fast before the Covid-19 pandemic, with emissions jumping by 32% from 2013-18. Flight numbers in 2020 have fallen by half but the industry expects to return to previous levels by 2024.

“If you want to resolve climate change and we need to redesign [aviation], then we should start at the top, where a few ‘super emitters’ contribute massively to global warming,” said Stefan Gössling at Linnaeus University in Sweden, who led the new study.

“The rich have had far too much freedom to design the planet according to their wishes. We should see the crisis as an opportunity to slim the air transport system.”

Dan Rutherford, at the International Council on Clean Transportation and not part of the research team, said the analysis raised the question of equality.

“The benefits of aviation are more inequitably shared across the world than probably any other major emission source,” he said. “So there’s a clear risk that the special treatment enjoyed by airlines just protects the economic interests of the globally wealthy.”

The frequent flyers identified in the study travelled about 35,000 miles (56,000km) a year, Gössling said, equivalent to three long-haul flights a year, one short-haul flight per month, or some combination of the two.

The research, published in the journal Global Environmental Change, collated a range of data and found large proportions of people in every country did not fly at all each year – 53% in the US, 65% in Germany and 66% in Taiwan. In the UK, separate data shows 48% of people did not fly abroad in 2018.

The analysis showed the US produced the most emissions among rich nations. China was the biggest among other countries but it does not make data available. However, Gössling thinks its aviation footprint is probably only a fifth of that of the US.

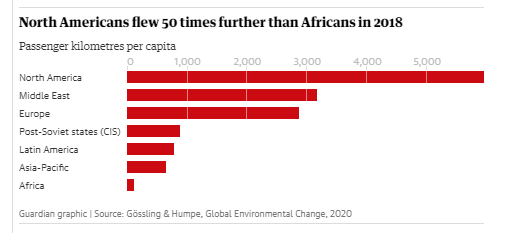

On average, North Americans flew 50 times more kilometres than Africans in 2018, 10 times more than those in the Asia-Pacific region and 7.5 times more than Latin Americans. Europeans and those in the Middle East flew 25 times further than Africans and five times more than Asians.

The data also showed a large growth in international flights from 1990-2017, with numbers tripling from Australia and doubling from the UK.

The researchers estimated the cost of the climate damage caused by aviation’s emissions at $100bn in 2018. The absence of payments to cover this damage “represents a major subsidy to the most affluent”, the researchers said. “This highlights the need to scrutinise the sector, and in particular the super emitters.”

The figure for the social cost of carbon emissions was actually a bit conservative, Rutherford said.

A levy on frequent fliers is one proposal to discourage flights. “Somebody will need to pay to decarbonise flight – why shouldn’t it be frequent flyers?” Rutherford said. But Gössling was less enthusiastic, pointing out that frequent flyers were usually very wealthy, meaning higher ticket prices may not deter them.

“Perhaps a more productive way is to ask airlines to increase the share of [low carbon] synthetic fuels mix every year up to 100% by 2050,” Gössling said. A mandate for sustainable aviation fuel starting in 2025 is backed by some in the industry.

A spokesman for the International Air Transport Association (Iata), which represents the world’s airlines, said: “The charge of elitism may have had some foundation in the 1950s and 1960s. But today air travel is a necessity for millions.”

He said the airline industry paid $94bn in direct taxes, such as income tax in 2019 and $42bn in indirect taxes such as VAT.

“We remain committed to our environmental goals,” the Iata spokesman said. “This year – in the teeth of the greatest crisis ever facing our industry – airlines agreed to explore pathways to how we could move to net zero emissions by around 2060.”

A key pillar of the industry’s plans is the carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for international aviation, produced by the UN’s air transport body. But this was heavily criticised in June when revisions were seen as watering down an already weak scheme, with experts estimating that airlines would not have to offset any emissions until 2024. “I think they have a zero interest in climate change,” Gössling said.

Other research by Gössling found that half of leisure flights were not considered important by the traveller. “A lot of travel is going on just because it’s cheap.”

He stopped flying for holidays in 1995 and more recently stopped going to academic conferences and taking long-haul flights. “I’m not saying I’ll never fly again. But if I can avoid it, I really, really try,” Gössling said.

17 November 2020

The Guardian