Global climate summit ends in failure. But the fight is not over.

The world is still not taking climate change seriously, and the planet’s largest polluters are still not committed to real change. Not all is lost, but this is a major alarm and a massive call to action.

t was a marathon session, the longest in history. Negotiators from over 200 countries gathered in Brazil Chile Madrid, Spain, for the so-called Conference of Parties — COP, for short — the meeting where world leaders plan how humanity can avoid catastrophic climate damage. Three years ago, the COP in Paris ended exuberantly: the most ambitious international climate agreement was agreed upon by the entire world.

Now, you could hardly imagine a more different outcome. ‘Defeated’ is a strong word but negotiators certainly didn’t leave feeling like winners.

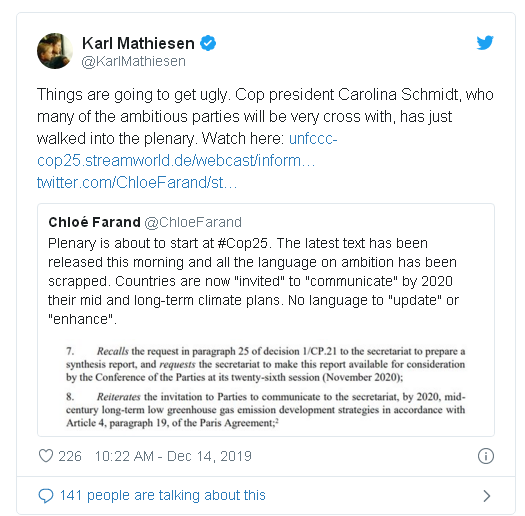

For the second year in a row, no agreement was reached on rules for international credit trading markets; an agreement to maybe, possibly, try to take ambitious steps to reduce climate change was also scrapped, largely due to opposition by large polluters. Yet again, nothing could be even remotely binding in the negotiations. Even when it comes to financing green projects, plans were dropped because of “disagreements on language”

In case you’re wondering what that means in real language, it means avoiding words like “will” and replacing them with “should” — removing any legal enforceability. The world couldn’t deliver an agreement because it didn’t want to be held responsible for that agreement.

There’s no sugarcoating it: the summit didn’t end as hoped.

“The negotiations fell far short of what was expected. Instead of leading the charge for more ambition, most of the large emitters were missing in action or obstructive,” said Helen Mountford of the nonprofit World Resources Institute.

The Trump effect

There was a noted change in attitude for some countries at this COP. As always, some partiers are more keen on addressing the climate than others, but the less eager ones were always pressured by the majority.

Now, emboldened by rising nationalism and a blatantly anti-science Trump, several countries stood up to protect their short-term interests or the interests of the groups that got them elected. Saudi Arabia, like Russia, wants to continue pumping oil and gas without consequence and maintain their geopolitical assets. In Brazil, Bolsonaro wants to weaken protections for the Amazon to benefit farmers. Australia’s recent leadership is extremely keen on its coal; and the US, well, it’s no surprise that they joined this group.

China, who at one point seemed to step up to climate leadership, also wavered. Trump’s announced withdrawal from the Paris Agreement

“There is a lot of disappointment with the outcome on this COP,” Krista Mikkonen, Finland’s environment minister, said after the meeting that was known as COP25. “No one can be proud. We are really lacking the big countries, the big economies to understand that we need action.”

In Paris, the world agreed to do what’s necessary to keep temperature rise below 2˚C above pre-industrial levels. After this year, the agreement is already underfunded and undersupported. It gets even worse.

The 2˚C figure is political rather than scientific — there is substantial research showing that we need to stay within 1.5˚C to avoid catastrophic damage — but the world isn’t even sticking to its 2˚C objectives. Like a true merchant of doubt, Trump did exactly what climate deniers wanted: he sowed doubt and uncertainty about the world.

But that’s far from the whole story.

The Greta effect

In truth, not all was bad at this COP. There was a lot of fight in many representatives, even through the disappointment.

“The international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation & finance to tackle the climate crisis. But we must not give up, and I will not give up,” tweeted UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

The very fact that negotiations were prolonged so much shows that some parties wanted to reach a consensus, and wanted improvement — it’s not unprecedented for negotiations to end early with no agreement. They couldn’t get something tangible, but there was still a fight to have there.

Low-lying countries, which have their very existence threatened by climate change, are starting to make their voices heard more and more — and it’s not falling on deaf ears.

Several countries (including European powerhouses) held firm — they’d rather sign no deal rather than a bad deal. This is particularly referring to global carbon markets: cap and cut mechanisms that would reduce climate pollution, harnessing the power of markets. Advocates of some mechanisms say they could shave $320 billion a year off the cost of reducing emissions by helping countries and companies identify the most efficient projects. But others were quick to point out that, if implemented incorrectly, they would be a disaster for climate efforts, providing polluters with the mechanisms to continue emitting without real consequences.

A group of 31 countries led by Costa Rica, and including Germany, the UK, Spain, and New Zealand opposed mechanisms proposed by Australia and Brazil, providing robust and reliable mechanisms for global carbon markets.

In a way, this was a reflection of what the voters want: in more climate-conscious countries, envoys were also more likely to support healthy climate actions.

Call this the Greta effect.

Youth activist Greta Thunberg was one of the most hotly-awaited participants at the summit. Say what you will about her (and many people certainly are), but the Greta that critics point their finger at doesn’t really exist. She does her best to act as a loudspeaker for the actual science — that’s always her message, “listen to the scientists“. But the Greta effect isn’t about science.

Greta showed people that they can stand up for something and demand change — from their social circles, from the companies they buy from, and from the politicians they vote into office.

More people than ever (and more youngsters than ever) are revolting against climate inaction. This message, at least, was heard loud and clear in Madrid — and politicians would be wise to heed it if they care about their electoral future.

Even in Trump’s America, most Americans believe in climate change and want action against it — when only a few years ago, they didn’t see it as a priority. That trend will only accentuate in future years, and it’s at the very least a ray of light in what was otherwise a pretty bleak result.

Neverending story

Chile’s Environment Minister Carolina Schmidt emerged to declare no deal had been reached after U.N. delegates negotiated for two weeks, breaking the record for the longest climate convention, after two unexpected extra days.

“Regretfully, after all the hard work that you have all done we couldn’t get to an agreement on this important article,” Schmidt, who presided over the summit, said. She was criticized by many as a weak president who set a very low bar for this year’s negotiations.

This COP truly felt like a neverending story — not in the sense that it was beautiful and magical, but rather because it was exhausting and full of unreal things.

A joke Twitter account was even set up (presumably by disgruntled participants)

But on a more serious level, the stakes have never been higher. Emissions are continuing to rise in the world, and they “would need to be 25 percent and 55 percent lower than in 2018 to put the world on the least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to below 2˚C and 1.5°C respectively.”

The US has voluntarily stepped down from its leadership position — although it’s noteworthy that despite the federal government, an impressive coalition of US representatives from local governments, business leaders, universities and many other institutions participated actively at the United Nations climate summit. Theirs is a laudable example — and an important one too, especially as it represents 70% of the GDP of the US, 65% of the population and over half of the emissions of the country.

The problem with not addressing carbon markets is a major failure. But not all the cards have been played yet. Bilateral agreements (such as the ones between the EU and China or EU and Japan) could play an important role and bring added leverage to negotiations — and this leverage is vital.

Polarization is becoming the defining theme in politics — and climate politics is no exception. But politicians often tend to forget one crucial thing: voters. Climate change is already affecting more and more people around the globe, and these people are making their voices heard. So too are the voices (and money) of those who see climate action as their demise. It will be a clash, but sometimes, progress can emerge from these clashes.

2020, Glasgow. Last chance

Many people are also awaiting a key event: the next US election. The US was one of the biggest supporters of the Paris Agreement. They did a complete U-turn — but they might do one yet again after the next elections.

“We’re in a very politically difficult time right now where we’ve got one key world leader denying climate change, so it’s very hard to get other countries to move forward when you’ve got such a critical country playing a spoiling role,” Ian Fry, a delegate from Tuvalu said. “That’s the state of the state of the world we’re in at the moment.”

Regardless of what happens to individual governments, consensus will be hard to find. It’s hard to imagine any consensus in next year’s COP in Glasgow. But consensus is not always needed when it comes to market progress — that’s why individual agreements between countries and blocs are so important. For now, we can place some hope into that, even in the absence of an international agreement.

But it truly feels like Glasgow 2020 is the last chance for the Paris Agreement. It’s a fitting place, too: a city known for its industrial prowess, Glasgow has grown far beyond its origins. Once dominant industries have been gradually replaced by other, diversified forms of economic activity. Nicolae Sturgeon, Scotland’s Prime Minister, is also a firm advocate of climate action, and has announced concrete plans to make Scotland climate neutral.

With better leadership and growing social pressure COP can still work, and it can still be a success. But it needs to send a stronger, clearer message.

“For Glasgow to be a success, we need a clear message that countries will be called to revise and improve their climate action plans,” said Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, an environmental group. “If that doesn’t come through, there’s going to be little that we can be able to harvest in Glasgow.”

16 December 2019

ZME SCIENCE