Are we safe? Of course not'.

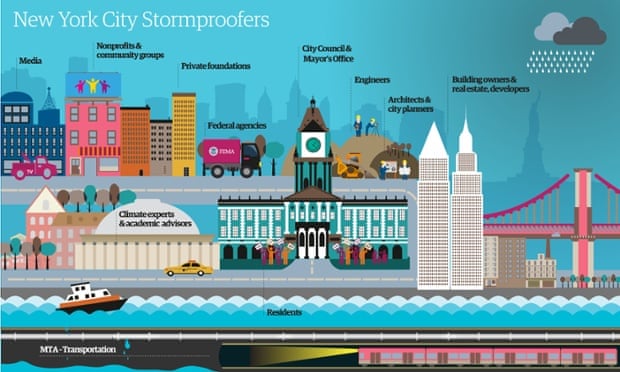

As part of our Stormproofing the City series, Klaus Jacob, who predicted the devastation wrought by 2012 storm, tells Lilah Raptopoulos why city planners could be making things worse, not better, for future generations.

Klaus Jacob has been saying the same thing for decades. But only now are people starting to listen to him.

In the fall of 2011, the esteemed Columbia University climate scientist published a prophetic report estimating how much damage New York’s subway system would suffer in the event of a major storm. One year later, when hurricane Sandy brought the Hudson river pouring into subway stations citywide, that report proved eerily accurate.

The press promptly named Jacob the Cassandra of NYC Flooding – a man whose valid, persistent warnings had gone unheeded for years.

“You can talk forever, but there’s nothing like an existential experience like Sandy to change our lives,” Jacob told me. “That’s when people suddenly remember hearing what you said.”

Jacob and I met at Columbia on a fittingly rainy day. He had agreed to explain how and whether New York City is protecting us from the next big storm for this series,Stormproofing the City.

Are we safe?

No. Of course we’re not safe. It’s only two years after Sandy, and the $50bn provided by Congress for post-Sandy resilience funding is only gradually trickling through the pipelines, from the federal through the state to the local communities. [Reporter’s note: less than a quarter of the funding has been paid out.] It’ll take at least another several years before that money is spent. The MTA is just getting their money now. What took almost two years to write a check?

When the city finally receives the funding, will it be meaningfully spent?

That’s the big question. By and large, government agencies and the private sector are doing more rebuilding than pro-building for the future. Some projects can actually make it worse for future generations.

Why?

Well, there are fundamentally three ways to adapt to climate change and sea level rising.

- One is protect: keep the water out.

- The second is accommodate the water. Invite it into the city. Make the city as immune as you can from the presence of it.

- The third, and the hottest potato politically, is strategic resettlement.Strategic resettlement is the most sustainable here, because New York has topography that other cities don’t. We have places like the Greenwood Cemetery that are 220 feet above sea level, where nobody lives except the dead! And we put the living in the water.

What are some of New York’s resilience measures that actually create risk for the future?

Take, for instance, the Big U, which came from the Housing of Urban Development’s Rebuild by Design competition. It builds a levy and dam system into a nicely designed park, a multipurpose structure.

The city should be proud of the project. Except … it has a fixed height. As the sea level rises, you need ever smaller storms to overcome it. It’s exactly New Orleans’ problem during Katrina. People think, ‘We have this Big U, we’re safe.’ But you’re building up risk behind the U until it becomes dysfunctional.

I’m not saying it will leak during the first ten years, but the sea level rise calculated is out to the 2050s. What about the 2080s? 2100? You just postpone the problem for future generations.

How can you get people to care about 2100? It seems so far away.

"I don't understand why we are almost unethical towards our children’s children."

I’m not saying we have to build the city today for 2100. I’m only saying we shouldn’t take measures now that become problems for the people living in 2100.

The whole basic concept of sustainability is to avoid intergenerational inequities and injustices. We throw around the word, but we’re violating that principle. The city has certainly done many wonderful things to become greener. But I don’t understand why we are so almost unethical towards our children’s children.

So tell me what the second way to adapt to rising sea levels – accommodation to water – would look like.

We could make downtown Manhattan like it was during the Dutch time – Broad Street was a canal. It had boats and ships. Let’s open it up again and let Water Street be Water Street and Canal Street be Canal Street. Venice on the Hudson!

So you’d then have to create submersible infrastructure for electric, gas, and communications – but we lay telephone cables across the ocean. We’ve run subways under the East River for over 100 years. Use the same technology! Build high lines for automobiles – raising normal traffic 30 feet will last you a couple of centuries.

If a storm like Sandy was to happen again tomorrow, would it be different?

No, it would be almost the same. Take the MTA: they recently received $300m from the Federal Transit Administration. It will take a few years to implement that. And what’s the money for? Stormproofing five stations downtown. That’s it.

What’s missing is the political will to do a rational assessment of costs and benefits. It’s so clearly worthwhile to incur some debt now to avoid downstream losses. But there’s something wired wrongly in our brains – we like to win lotteries, not put a dollar down now to save four later.

We need a lot more Katrinas and earthquakes and storms before we get smarter.

How much of the efforts here in New York reflect other cities in the US?

Other cities, other problems, other solutions … or no solutions. San Francisco is looking carefully, though they worry more about earthquakes. Kings County in Seattle is doing nice things. A group in New Orleans is working toward letting the water in – a laudable effort – though I’m not sure what chances they have. Houston has taken care of its urban flash flooding, but there are big problems with sea level rising there in the future.

And Miami: forget it. The highest place you can live in Miami is only 18ft above sea level. Miami, no.

"Miami, forget it. In 100 or 200 years, I’m not sure whether anybody will know where Miami is."

Why?

Even if you believed in protection, it wouldn’t work there. Miami sits on sponge-like limestone, which is worse than swiss cheese: the holes are all connected to each other. If you build a dam or levy on it, the water just flows underneath.

In 100 or 200 years, I’m not sure whether anybody will know where Miami is.

Some of the things you’re saying are scary and may be hard for people to hear.

It shouldn’t be scary.

Why not?

It provides incredible opportunities to fix problems that we otherwise wouldn’t be able to dream of. We can build entire new cities, or amendments to cities, in the way we want them. What’s so scary about that?

I mean, look. I grew up as a young boy just when world war two ended. It was a miserable time. Who ended up renewing all its infrastructure and rebuilding? Japan and Germany. It all turned into an opportunity.

As I continue my interviews [in this series], what sorts of answers should I take with a grain of salt?

Always question if you hear someone say that the post-Sandy recovery was a success. No. It was not a success.90% of applicants for the city’s Build it Back program haven’t seen any financial assistance. Come on.

What amazes me are the proposals that haven’t been tabled – like Seaport City, which supports new luxury housing at the waterfront, in harm’s way. They argue that if you build it high enough, it’ll protect the neighborhoods behind it. Give me a break. That may be true for a couple of decades, but fundamentally it’s a misinvestment.

The real estate sector is extraordinarily influential in this city. The mayor’s office tends to be more or less beholden to it. What I’m saying goes against what they’ve been preaching for 30 years: that a waterfront apartment is a good investment.

What else needs to be done to protect New York from future storms?

We still have no serious plan for the people in the Rockaways and Red Hook. We do have temporary walls in Red Hook, and I like that they don’t pretend to be permanent. They look like the Band-Aid that they are. But you can’t wear a Band-Aid for long, particularly when the wound keeps bleeding. You have to do something about it.

Would places like the Rockaways and Red Hook benefit from your third way to adapt – “strategic relocation”?

Yes. Let’s create waterfront parks and start to resettle the higher grounds. It takes 50–100 years to shape a new city. We have to start putting financial instruments in place sometime.

What are financial instruments?

We have examples of things that work. NGOs go to farmers in upstate New York and say: “You stay and farm as long as you want, but if you want to quit, let us buy the land. Don’t sell it to developers. We’ll ensure that it stays farmland.” We could go to people in the Rockaways and say, “If you’re ready to leave, sell to us, the public. We’ll help you find a new place to settle.”

Is there anyone else I should talk to that could help me understand how New York is being stormproofed?

Ask the Federal Reserve how to finance something like resettlement – how to make public bonds, how to have Goldman Sachs put a little brains into it.

Also call [director of the mayor’s office of recovery and resiliency] Dan Zarilli. He thinks I’m his nemesis, but he’s smart as hell. I’m always holding him accountable for short-term thinking with Seaport City. Sure, I don’t have to deal with politics and the real estate industry – I don’t envy his position. But that doesn’t make him right.

Last question: what keeps you up at night?

My sleep is very good.

Ok. What’s your biggest fear?

That we will muddle along and lose time that we could have spent so much more productively. Yes, we are of different minds politically, but Mother Earth doesn’t care whether you’re rich or poor or what state boundary you live on. And unless we find consensus that we’re in trouble, we’ll be in trouble.

This interview is part of a series called Stormproofing the City.

The Guardian