EU on track for 50% emission cuts by 2030, study says.

While Germany and Eastern European countries continue to oppose raising the EU’s 40% emission reduction target for 2030, a new analysis insists the bloc will actually manage at least 50% cuts under a business-as-usual scenario taking into account the latest coal phase-out pledges.

EU leaders agreed in 2014 to adopt the 40% target but their decision predated the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, which seeks to keep global warming to well below two degrees Celsius.

There is now wide consensus among climate experts that 40% is inadequate if the EU intends to honour its commitment to the agreement, which was reinforced by a stark UN report last year that looked into the negative effects of warming above 1.5°C.

The European Commission has acknowledged that the target is out of date. After running its energy and climate numbers again in June, the institution revealed that new laws on renewables and energy efficiency would yield “de facto” cuts of around 45%.

On Tuesday (26 March), an in-depth study by climate think-tank Sandbag concluded that 50% should be the EU’s business-as-usual scenario, after taking into account national pledges to phase out coal power.

Sandbag’s model includes all the phase-outs already on the books, including France (2021), Italy (2025) and the Netherlands (2029). The study predates Germany’s recent announcement of a 2038 cutoff point for coal but the model also assumed a 2040 phase-out for every other country.

The Commission’s latest models show there will still be 371 terawatt hours (TWh) of coal power connected to the grid in 2030, while Sandbag estimates just 198TWh, which accounts for the discrepancy between their two targets.

Suzana Carp, Sandbag’s EU expert, said at the study’s launch event that “it’s good to see even a conservative model providing a higher number”. Two other scenarios showed that tweaks to policies and more ambitious phase-out dates could lead to cuts of 53% or even 58%.

The study concluded that “there is a substantial opportunity for confidently adjusting the existing 2030 target, to go beyond the new business as usual of a 50% cut”.

However, Yvon Slingenberg, a director at the European Commission’s climate directorate, was more cautious. Speaking at the event, she said “emphasis needs to be put on the long-term strategy [for 2050]. Our modelling shows 45% is the baseline if everything is implemented. So it is actually at the discretion of the member states.”

How to do it

Increasing the so-called nationally determined contribution (NDC) for 2030 is supposed to require unanimous approval from the member states, which turns it into a politically-charged issue.

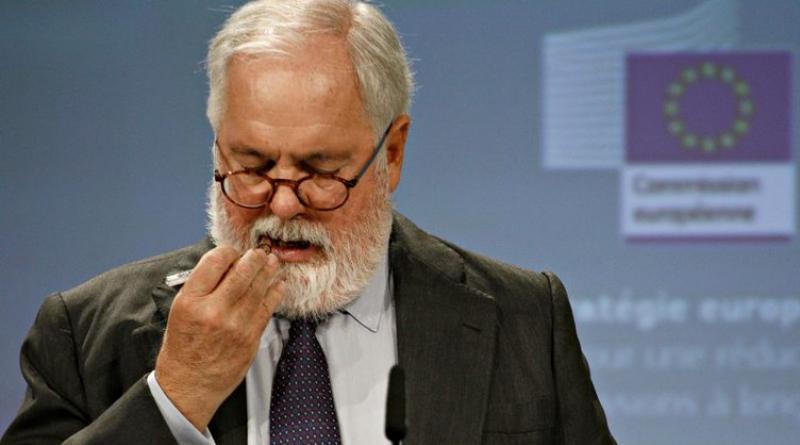

EU Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete tested the waters last summer but leaders like Germany’s Angela Merkel made it clear that increasing the NDC was off the table for now.

There are plenty of other critics still opposed to bumping up the target: Central and Eastern European countries are generally against raising the EU target, while climate-progressives like the Netherlands and Sweden consider 45% too low a benchmark.

Members of the European Parliament are also in favour of something more ambitious. In a resolution adopted on 14 March, they called for the NDC to increase to 55%.

Cañete had reportedly hoped to secure an increase to 45% before last December’s COP24 summit in Poland, in order to strengthen the EU’s position as a climate champion, but abandoned the idea when it became unfeasible.

Still, the Spaniard used the 45% benchmark to calculate the figures in the European Commission’s landmark 2050 long-term strategy, published ahead of the December UN climate summit, which made the case for reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century.

EURACTIV understands that the current Commission has not totally abandoned hope of getting the 45% figure approved, in order to boost the chances of getting full backing for the 2050 plan and avoid turning up empty-handed at the UN general assembly in September.

At last week’s EU summit, national leaders backed the Commission’s suggestion that Europe’s economy should hit net-zero emissions but failed to put an actual date on it.

Commission sources told EURACTIV that, despite appearances, any conclusions on the climate plan at this stage, following its debut in November, represent progress and there will still be time to convince more sceptical countries.

The group of sceptic nations includes usual suspects Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, as well as Germany, which opposed including 2050 specifically in the summit conclusions.

A crucial event for climate is in May, when EU leaders are expected to talk about the strategy again at an informal meeting on the future of Europe in Romania, and then again at a regular EU summit in June.

Commission officials expect EU leaders to endorse the climate plan at the October summit, so that the bloc can submit it to the UN before the next COP meeting in Chile.

28 March 2019