The World’s Sharks Face a Gauntlet of Threats From Marine Heatwaves—and ‘Coldwaves,’ Scientists Say

Over the last 450 million years, sharks have survived five mass extinctions, making them some of the oldest—and sturdiest—creatures still in existence today.

But a sixth mass extinction that many scientists fear is underway could be too much for these fierce predators.

In recent years, overfishing and ocean degradation have pushed many shark species to the brink. Now, a growing number of studies are unraveling some of the unique ways that ocean warming—and in some cases, ocean cooling—fueled by human-caused climate change could disrupt shark populations and reproduction if emissions continue to rise.

Cooking Eggs and Shifting Prey: Around 40 percent of the more than 500 species of sharks swimming in the ocean lay eggs rather than giving birth to live pups, estimates say. The embryos within these eggs incubate in the conditions that surround them, which could be a problem as the ocean gets hotter and acidifies, according to a study published in June.

To determine just how much of an issue this could be, a team of researchers tested eggs from the small-spotted catshark—one of the most abundant shark species in Europe—under different temperatures and acidities based on various emissions scenarios. While they found that moderate emissions would likely have a small impact on egg development, the rapid expansion of fossil fuels around the world could cause catastrophic declines. When they tested water that was around 72 degrees Fahrenheit—7.9 degrees hotter than in recent decades during the summer in western and central Europe—just 11 percent of the shark embryos hatched.

“We were shocked,” Noémie Coulon, a doctoral student at the Laboratoire de Biologie des Organismes et des Écosystèmes Aquatiques in France, said in a statement. “The embryos of egg-laying species are especially sensitive to environmental conditions.”

Past research has found that hot ocean temperatures could cause some sharks to hatch early, resulting in smaller and less healthy pups in species like the epaulette “walking” shark, nicknamed for its ability to temporarily crawl on land. But the complex effects of ocean warming and acidification extend well beyond the beginning of a shark’s life.

Studies show that warmer ocean temperatures are speeding up sharks’ metabolic rates, forcing them to use more energy just to swim and stay alive. While some species, like the shortfin mako shark, are diving deeper to find cooler waters, ocean warming is also creating newly suitable habitats for sharks in certain parts of the world, primarily northward, Yale e360 reports.

This may sound like a good thing, but sharks popping up in new places could cause an uptick in human-wildlife conflict. For example, tiger sharks have expanded in the northwest Atlantic Ocean over the last several decades as this region has warmed, pushing them beyond management areas that are closed to longline fishing and increasing their chances of being caught accidentally, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Climate change could also affect a shark’s ability to find prey as fish and squid migrate to new areas in response to warming waters, studies show.

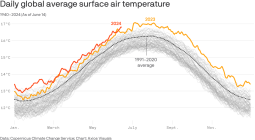

Cold Snaps: As a whole, global ocean temperatures have been at an all-time high over the past year, causing marine heat waves that have decimated coral reefs, which my colleague Bob Berwyn covered in May.

However, climate change may also be triggering more “coldwaves” in parts of the ocean. That can have equally devastating consequences for marine species, including sharks, according to a study published in April in Nature Climate Change.

When winds blow across the ocean surface, they can push warm water away from the coast, which is then replaced by cold water from greater depths through a process called upwelling. Local upwelling events—essentially ocean cold snaps—have become increasingly common in certain parts of the world over the past 40 years as climate change alters wind patterns, currents and surface ocean temperatures, according to the recent research.

The study points to a “coldwave” that spread across South Africa’s southeast coast in 2021, where temperatures dropped from 70 degrees to 53 degrees in under 24 hours. The researchers say the event killed hundreds of animals, including several bull sharks. By tracking bull sharks in South Africa and Australia, they discovered that these predators are expanding their range as ocean waters warm, but frequently have to dodge chilly upwelling events that could kill them along the way, resulting in “bait and switch situations,” according to the study.

“This really shows the complexity of climate change, as tropical species would expand into higher-latitude areas as overall warming continues, which then places them at risk of exposure to sudden extreme cold events,” study authors Nicolas Benjamin Lubitz and David Schoeman wrote in the Conversation.

“In this way, species such as bull sharks and whale sharks may very well be running the gauntlet on their seasonal migrations.”