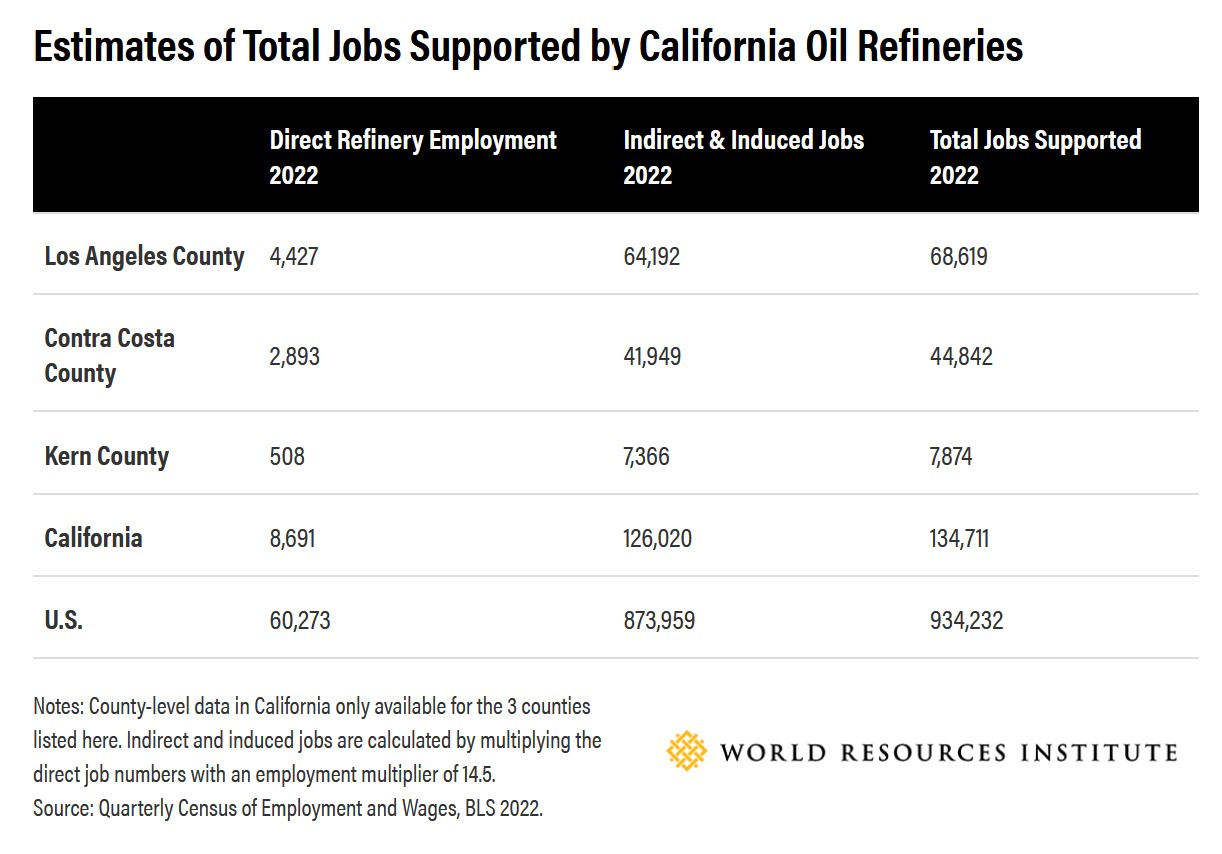

Most refinery jobs are high quality, union jobs — with good wages and benefits that have been negotiated over many decades as a result of the industry’s long history of striking for better working conditions. Oil refinery workers, including management positions, make over $190,000 per year on average, compared to $84,500 for all private sector jobs in California. The state’s petroleum pump system operators, refinery operators and gaugers, one of the key occupations in the industry, earn $97,030 per year on average.

Workers have been advocating to improve job quality within the new clean energy economy, as labor unions are concerned that the clean energy transition will erode job quality, wages and benefits. Making sure that labor is well represented in planning discussions will therefore be critical for ensuring the state has a “just transition.”

And the potential impacts of a refinery phasedown extend far beyond refinery workers and their families. Refineries provide tax revenues that support funding for adjacent communities’ public schools, healthcare, and infrastructure like roads and parks. Lack of quality data on refinery tax revenue hinders our understanding of their contribution to the local economy, but available evidence suggests it is significant. According to one analysis, the closure of seven refineries across the U.S. between 2019 and 2022 cost the communities hosting them a collective $21 million in local property tax revenue annually. Similarly, St. James Parish in Louisiana estimated it would lose $24 million annually in property, inventory and sales tax when Shell decided to close its refinery in 2020.

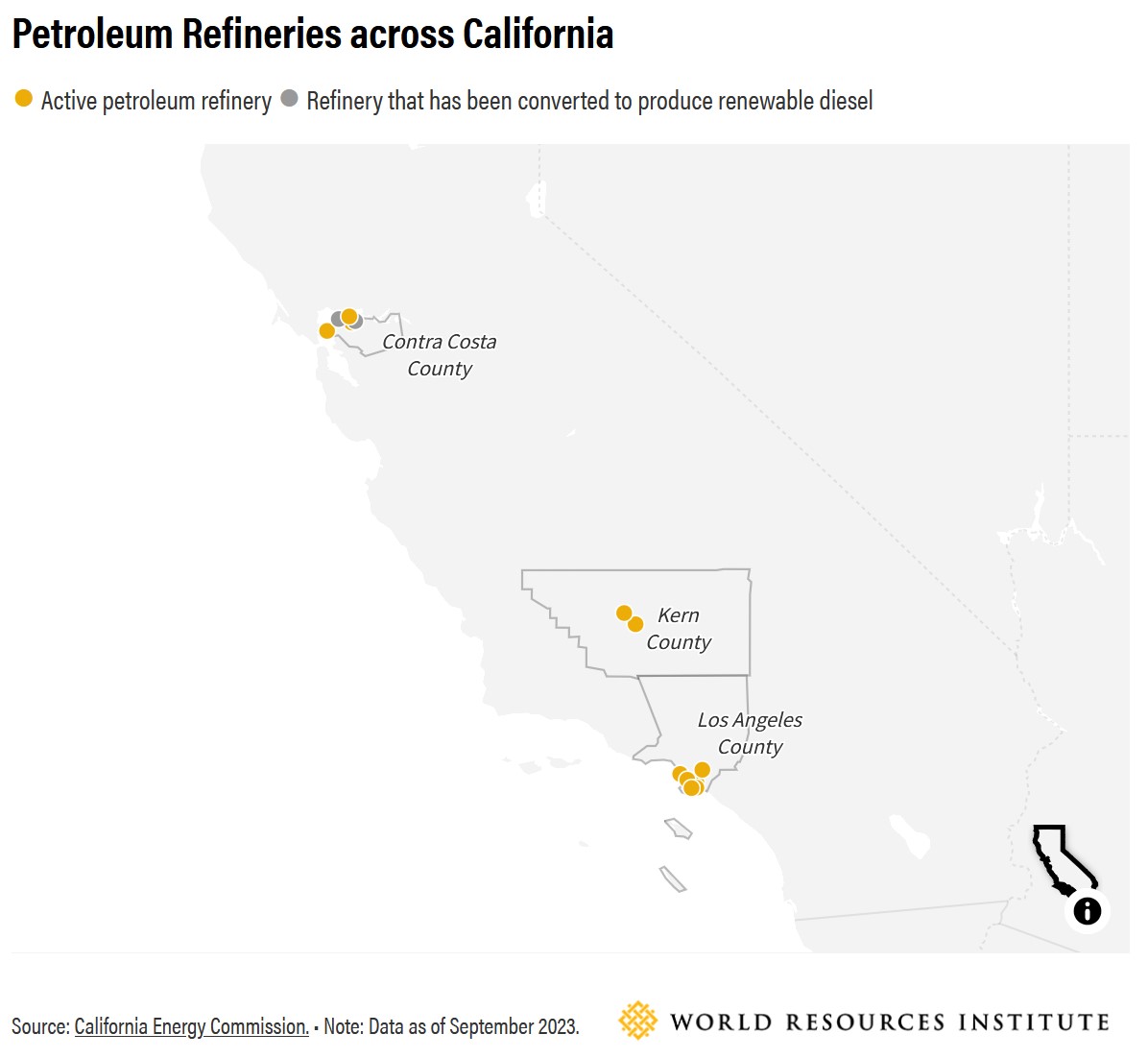

There’s also an environmental justice component to refinery phasedowns. Black Americans are 75% more likely than other Americans to live in neighborhoods adjacent to refineries. More than 50% of residents in Los Angeles County, where many of California’s refineries are located, live in disadvantaged communities that suffer from a combination of economic, health and environmental burdens. While the closure of refineries could bring a much-needed reduction in air pollution in these communities, left-behind compounds like lead and benzene can continue to pollute soil and water long into the future, raising questions about environmental remediation and who pays for it. For instance, Marathon’s Gallup refinery in New Mexico “idled indefinitely” instead of officially closing, avoiding the expensive task of cleaning up the polluted site.

What's Needed to Ensure California’s Oil Refinery Phasedown Doesn’t Come at the Expense of Workers and Communities?

California needs to develop a transition roadmap that holistically considers refinery workers’ and communities’ needs.

Los Angeles County is leading the way through its Just Transition Strategy, meant to support workers and communities impacted by the phase-out of oil drilling and extraction (though it omits refineries). At the state level, however, there is no simultaneous effort to develop a just transition roadmap for the entire oil industry, including its refineries. California is currently producing a fossil fuel phasedown plan, devised by a multi-agency task force and incorporating the results of a transportation fuels assessment. It’s essential that this plan look beyond just how to reduce emissions and include how to protect the workers and communities reliant on the fossil fuel industry.

We’ve already seen what an unplanned transition looks like in other states, with severe labor market shocks and community-level impacts. Take coal mining in Appalachia: 87% of U.S. coal-related job loss has occurred in Appalachia due to declining coal production and closure of coal-fired plants.

California therefore needs a state-level plan for a well-managed and just transition. A few considerations will be essential as policymakers create a roadmap:

1) A better understanding of workers’ needs

Any policies to support refinery workers in the low-carbon transition need to be informed by workers themselves.

A recent UC Berkeley Labor Center study is one of few that places refinery workers’ experiences and recommendations at the forefront. It focuses on workers that were laid off during California’s Marathon Martinez refinery closure in 2020, specifically their recommendations on job search assistance, job training programs, financial planning and retirement preparation assistance. More recently, the Steelworkers Charitable and Educational Organization (SCEO), a non-profit connected to the United Steelworkers union, was one of several groups to win a grant from the Displaced Oil and Gas Workers Fund to craft training programs and job placement services to help prepare displaced workers. These insights can inform policymakers and help place workers’ needs at the forefront of future policies.

A better understanding of refinery workers’ current occupations, educational backgrounds and skills is also crucial. Refineries include a variety of roles, requiring all levels of education and training. Some skills are industry-specific, and some are readily transferrable to other industries. While some jobs usually require a high school diploma and a few months of training, others require a four-year bachelor’s degree. A UK oil and gas workforce analysis found that over 90% of its workers have medium to high skills transferability, putting them in a strong position to work within other clean energy-related sectors, though such jobs might not always be located in the same region where refinery workers are being displaced.

2) Data to help proactive planning

Decreases in demand will likely lead to the closure of many of today’s 11 petroleum refineries in California. Obtaining refinery-specific data will be crucial to prepare and understand how different refineries would be impacted by the phasedown of refined petroleum products — including which will close quickly, and which are more likely to remain around longer and/or be converted to alternate uses, such as renewable fuel production. But it’s currently difficult to access this data. Much of it is proprietary or doesn’t exist in the form of accessible datasets.

California’s Marathon refinery was closed in August of 2020, shortly after being idled due to decreasing demand linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. The abrupt closure left its workers feeling blindsided and unprepared for the mass layoff. The PES refinery in Philadelphia also closed within the same timeframe, after it declared bankruptcy following a significant explosion. These examples underscore the importance of tracking the economic and operational health of refineries to allow for better planning around their closures. This is crucial to ensure that workers and communities receive the necessary transition support, and that taxpayers don’t end up paying for a bankrupted facility’s clean-up and remediation.

Publicly accessible data on the local government revenue generated by refineries is also needed, as it supports cities’ general budgets and funds education, health and public services. Some studies explore how the overall oil and gas transition would impact local governments’ finances, yet more revenue data is needed at the local level to fully understand future impacts and what’s needed to replace refinery revenue.

3) Comprehensive modelling to understand likely impacts

California has already funded two modelling studies on enhancing equity and reducing emissions of its transportation fuels. They examine different pathways for reducing California’s transportation fuel demand and supply to achieve carbon-neutral transportation by 2045, while also considering labor and health impacts. The state’s latest Scoping Plan points to these studies, and their results will also likely be considered within the fossil-fuel phasedown plan being developed by the state’s multi-agency task force.

While the studies provide foundational modelling, the state needs to consider a wider range of future scenarios for petroleum demand, which will impact its refinery phasedown planning. For example, scenarios should account for the demand of renewable fuels and consider the potential use of clean hydrogen and/or point-source carbon capture and sequestration.

The state should also better map out the impact of different export scenarios that consider California’s competitiveness in other domestic and international markets. The demand for oil in other states and countries (which are also electrifying, although at different rates) will have impacts on California’s refineries. While not enough is known about whether California refineries are positioned to increase exports, some environmental groups have raised concerns about the state increasing its fuel exports, prolonging the life of its petroleum refineries.

More comprehensive modelling must also consider air pollution, health, jobs and tax revenue impacts on surrounding communities from either refinery closures or conversions to other uses. The workforce and long-term tax implications of switching to produce renewable fuels, in particular, need to be better studied. In 2020, the Cheyenne refinery in Wyoming announced it would lay off the majority of its workers as it transitioned into a renewable diesel plant. Any state-level plan needs to carefully consider biofuel-related economic impacts when moving toward the ultimate goal of electrification.

4) Inclusive planning

There are lots of stakeholders with varying perspectives on just transition policies, from environmental NGOs and environmental justice groups to labor unions and industry representatives. It will be crucial for the state to engage with each of them.

Environmental justice and conservation groups have long advocated for more stringent safety regulations and the decommissioning of refineries. They’re now raising concerns over the state’s interest and policies around the use of biofuels, hydrogen, and carbon capture and sequestration as part of the low-carbon transition. One group recently sued the City of Paramount over the approval of a biofuel refinery expansion without adequate environmental review, citing health and safety concerns.

Oil industry trade groups like Western States Petroleum Association, on the other hand, have a strong influence on California policymaking and have regularly opposed policy proposals focused on phasing out oil production and other transition-focused bills. While some labor unions have at times shared the association’s resistance due to concerns about losing well-paying union jobs, other labor groups are more welcoming of the low-carbon transition.

The United Steelworkers Local 675 launched a coalition of labor unions in 2023 to advocate for a worker-led just transition, one of several labor groups that endorsed a 2021 report outlining a roadmap towards a clean and equitable energy transition in California. Labor unions have also been central to the design and implementation of two initiatives focused on worker transitions: the state’s Displaced Oil and Gas Workers Fund, set up to provide help to displaced oil and gas sector workers to transition into sectors that match their skills and offer comparable wages, and the Oil Well Capping Pilot Program to train displaced oil workers to participate in capping abandoned oil wells. Closely engaging with labor groups will be crucial for the transition to be successful both for people and the climate.

Multi-stakeholder coalitions can play an important role in bringing these different perspectives to the same negotiating table. This is already happening in the context of Northern California refineries, where the Contra Costa Refinery Transition Partnership, a labor environmental justice partnership led by the BlueGreen Alliance Foundation, is developing strategies to prepare for the refinery transition. This partnership brings together oil refinery workers, community organizations, industry representatives and other key stakeholders.

California Can Create a Model for a National Just Transition

There are already numerous examples within the energy industry that illustrate the harm of an unplanned low-carbon transition. As policymakers in California consider their plan to phase down refined petroleum products, it’s essential they also develop a transition roadmap that holistically considers workers’ and communities’ needs.

California’s ambitious policies signal that the state’s refineries could be the first in the country to undergo a significant transition and shift away from fossil fuels. The state therefore faces an unprecedented opportunity: demonstrating what a just and clean refinery transition can look like — not only in California, but for other states also grappling with the unintended consequences of a clean energy future.

Rajat Shrestha also contributed data analysis to this article.