Who are the polluter elite and how can we tackle carbon inequality?

Who are the polluter elite and why do they matter?

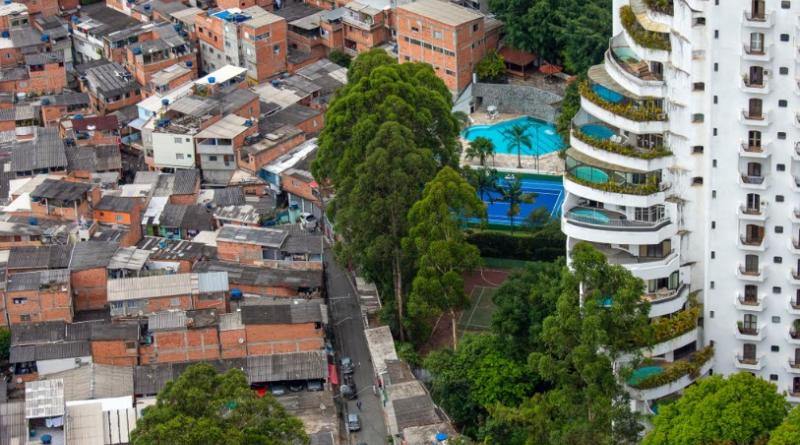

The richest 1% of people are responsible for as much carbon output as the poorest 66%, research from Oxfam shows. Luxury lifestyles including frequent flying, driving large cars, owning many houses, and a rich diet, are among the reasons for the huge imbalance.

Jason Hickel, an economist, argues: “We have to think about the rich in terms of how much they are depleting the remaining carbon budget. Right now, millionaires alone are on track to burn 72% of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C. The purchasing power of the very rich needs to be curtailed. We are devoting huge amounts of energy to facilitate the excess consumption of the ruling class – in the midst of a climate emergency, that is totally irrational.”

The problem goes far beyond the greenhouse gas emissions arising from these lifestyles, substantial though they are. The polluting elite have an outsized influence on the climate in many ways. Hickel notes: “While personal consumption-related emissions are important, what matters most is control over investible assets. When we account for investments in polluting industries, we find that each billionaire is responsible for a million times more emissions than the average person in the bottom 90%. Who is making the decisions about investment and production in the world economy? About energy systems? When it comes to the question of responsibility, that’s what we need to be focusing on.”

Meanwhile, poorer people are facing “double jeopardy” because of the spiralling impacts of the climate crisis and economic inequality, says Mariana Mazzucato, an economist at UCL and an adviser to governments, quoting Barbados’s prime minister, Mia Mottley. That is because richer people in the global north bear most responsibility for the accumulated greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, and have reaped the benefits of carbon use, but now poor countries are bearing the brunt of the damage caused by those emissions and facing “massive financial constraints in responding to those challenges they didn’t create”, Mazzucato says, which is impoverishing them further.

“So the double jeopardy is like, we’re getting screwed twice,” says Mazzucato. “Low-income countries are currently allocating more than twice as much funding for servicing their debt as they do to social assistance, 1.4 times more than they do to healthcare, and much more than they can to climate adaptation. So how do we actually find ways for them to be able to tackle these climate challenges which have been caused by the north in such a way not to [push them] further into this debt spiral?”

It is simply impossible to have a polluting elite and a livable climate, argues Farhana Sultana, professor at Syracuse University and fellow at the International Centre for Climate Change and Development in Bangladesh. Along with many developing country economists, she regards the high emissions of rich people in industrialised countries in terms of colonialism. “Carbon inequality is effectively a colonisation of the atmosphere by the capitalist elite of the planet through hyper-consumption and pollution, while the cost of that climate coloniality is borne disproportionately by the marginalised and vulnerable communities in developing countries.”

The culture of rich people, and rich countries, built on use and discard cannot continue in a world of finite resources and planetary boundaries. “What the 1% do is overuse the earth’s resources through extraction, hyperconsumption, a discard culture that produces enormous amounts of waste and pollution – all these processes together create significant strains to planetary systems,” she says.

Kevin Anderson, a climate scientist, says the 1% of richest emitters also influence far wider consumption. “The 1% group use their hugely disproportionate power to manipulate social aspirations and the narratives around climate change. These extend from highly funded programmes of lying and advertising to proposing pseudo-technical solutions, from the financialisation of carbon to labelling extreme any meaningful narrative that questions inequality and power. Such a dangerous framing is compounded by a typically supine media owned or controlled by the 1%. The tendrils of the 1% have twisted society into something deeply self-destructive.”

What can be done to tackle carbon inequality?

Inequality is a problem, but several economists pointed out that it also presents a possible solution. “In a perverse sense, this is good news: if only a relatively small proportion of people are causing the problem, then it may be easier to target them when trying to find solutions,” says Roman Krznaric, the author of The Good Ancestor.

Policies that target the super-rich could range from banning private jets (favoured by the French economist Thomas Piketty), or taxing them heavily, to wealth taxes, carbon taxes, consumption taxes, windfall taxes on the bumper profits of oil and gas firms, and potentially of other high-carbon industries, and frequent flyer levies.

These would raise revenue that could be redirected internationally towards assistance for poor countries, including the loss and damage fund for the rescue and rehabilitation of countries and communities stricken by climate disaster, and domestically within richer countries to help people on lower incomes gain access to low-carbon technology, such as heat pumps.

Regulation will also be necessary, several economists argue, to change the world’s energy systems, require minimum standards of efficiency, and outlaw some of the most polluting activities.

Julia Steinberger, of the University of Lausanne, argues that debt forgiveness for poor countries should also be included, as well as investing in efficient and sufficient low-carbon public services, from housing retrofit to public transit, and including healthy, affordable plant-based food provision.

Hickel would go further and “actively scale down less necessary forms of production – things like mansions, weapons, aviation and fast fashion”. He would also extend public control to the private sector. “We clearly need to bring a greater share of money creation and investment under public control. Under capitalism, investment is directed to what is most profitable to capital. So we produce a lot of SUVS, aviation, fast fashion, industrial meat, because these are highly profitable. But we get far too little investment in necessary things like renewable energy and public transport. We need more democratic control over investment, so we can direct investment towards things that are socially and ecologically necessary.”

The sums needed to help developing countries cope with the impacts of the climate crisis and shift their economies to a low-carbon footing sound enormous: more than $2tn a year, according to some estimates. Mazzucato argues that this is not as alarming as it might appear. “There’s so much finance out there. There is no finance gap, no lack of finance. We just aren’t directing it in the right way,” she says. As well as public funds, there is money from private-sector investors, most of which is directed toward high-carbon activities and could be repurposed, and revenue from potential new levies.

Vera Songwe, an economist from Cameroon who headed the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa and is now at the Brookings Institution in the US, favours “a true, honest price for carbon” as a way to bridge the carbon divide. Accounting for emissions in this way, as well as penalising high-carbon activities, could reward developing countries that have large carbon sinks, in the form of forests, peatlands or coastal swamps, and encourage them to keep these important landscapes intact.

“It’s really important to think of the contributions that developing countries make in this way, and to reward good behaviour,” she says. “We can tackle the climate crisis at the same time as doing development [in the poor world]. We can make choices about the quality of growth we pursue.”

Jayati Ghosh, at the University of Massachusetts in the US, says deep cuts in emissions from the rich are needed now, but poor countries might need a larger slice of the remaining carbon budget in order to grow. This will require a response that goes beyond national emissions targets, to penalise excess emissions from the rich across the world, and control extreme wealth through taxes. There is no more time for tinkering at the edges of economic policy, she adds.

“Taking a few incremental measures may feel good, but these are unlikely to have much real impact. There is really no alternative to drastic changes in our economic systems and strategies, which also involve significant reductions in inequality. We can keep talking around this, but unfortunately nature and the planet are not listening, they respond only to our actions.”

She adds: “Providing basic needs and ensuring a life with dignity can be achieved at relatively little carbon cost, with appropriate public investment – which could indeed be financed through taxes on the rich and on large global corporations.”

How can we reduce inequalities within countries?

Inequalities are not just between the global north and the global south: research from Oxfam shows that the differences in carbon footprint of rich and poor people within countries are now greater than the differences between countries.

Climate policies must be carefully tailored to ensure that people on lower incomes are not bearing a disproportionate cost burden, argues Piketty, the author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Otherwise, a backlash – like the gilets jaunes protests in France – is likely.

Rachel Cleetus, a policy director for climate and energy at the Union of Concerned Scientists in the US, says: “Within richer countries like the US, there must be a parallel effort to address the loss and damage [from the climate crisis] domestically. Black, Brown, Indigenous and low-income communities have been historically overburdened with fossil fuel pollution and are now on the frontlines of a climate crisis that is largely the making of richer people. The international and domestic aspects are two halves of the same problem and both require a justice-centred response.”

The rapidly widening inequalities within developing countries mean we cannot treat all people as having the same interests, argues Adair Turner, a co-chair of the Energy Transitions Commission thinktank. Poor countries have their own cadres of well-off people with high-emitting lifestyles. “Sometimes you can get rich people in India and China giving the per capita average [of carbon emissions] for India and you do have to occasionally say, yeah, but hang on, I happen to know your personal carbon footprint is as high as mine,” Lord Turner says. “So let’s sometimes talk about rich versus poor, not country versus country.”

This can also be an issue at UN climate summits, notes Steinberger. “Unfortunately, many national negotiators seem to align with the interests of the wealthiest, rather than the majority within their countries.”

How can we reduce inequalities between generations?

Many economists also make the point that climate inequalities exist not just between countries and regions, and social and economic classes, but between generations. For example, data shared with the Guardian shows that in the UK, baby boomers have the largest and growing carbon footprints, significantly higher than generation X and millennials.

We are bequeathing to our children a world in which the carbon budget has been used up: what will that mean for them?

“Governments have an obligation to act on behalf of the collective good,” says Peter Newell, of Sussex University. “If a small percentage of the global population is over-using their fair share of carbon budgets, they are passing on the burden of responsibility to others within their societies and in other countries, or pushing on costs to future generations. Governments have to enforce fair shares to remaining carbon budgets.”

Mohamed Adow, the founder of the Power Shift Africa thinktank, says poor countries can avoid the traps of high-carbon development that industrialised countries used in the past. “The good news is that renewable energy can power economic development,” he says. “My country of Kenya has a 92% renewable electricity mix and is one of the more prosperous African countries.”

He counsels against developing countries trying to bridge the economic divide by exploiting their fossil fuel reserves, pointing to Mozambique where foreign companies have built a $20bn offshore natural gasfield and onshore LNG facility, but 70% of the country has no electricity access. “The gas is not for local people,” he says.

Is capitalism the problem?

Many thinkers today see carbon inequality as the outcome of a much bigger problem: capitalism. According to Daniela Gabor, an associate professor in economics at the University of the West of England, we need states to undertake an “extensive, deep intervention in the reorganisation of economic activity that is necessary for a just transition. Carbon wealth taxes don’t even begin to scratch the surface of that transformation.”

Hickel wants “democratic control over investment … and production”, because profit-seeking markets prioritise the wrong things. “When people have democratic control over production, they prioritise human wellbeing and ecological sustainability,” he says.

A growing number of economists are arguing for governments to target “degrowth”, as economic growth can lead to overconsumption. Mazzucato disagrees. “I just don’t think it makes any sense. That’s not the problem most of the world is facing. Most of the world is facing no growth. Most of the world doesn’t have employment. So what we actually need is a very different way to grow.”

Greenhouse gas emissions must halve this decade and reach net zero in just over 25 years to stave off the worst impacts of climate disaster. Yet emissions are still testing record highs. This is why some climate experts argue that we cannot wait for sweeping reforms of our political and economic systems to bring about a more equal society, but must do what we can now with what we have.

Nicholas Stern, the chief economist at the World Bank before he wrote his landmark review of the economics of climate change in 2006, said: “There are very important arguments around tackling inequality, for all sorts of good reasons – health, education, development as well as the environment, and emissions – and these arguments are very powerful. But if you say that you have to wait for that [inequality to be eliminated] before you cut back emissions, then you are misunderstanding the complexity and misunderstanding the opportunities. If you had to wait for a radical rewriting of inequality across the world, we would be too late. We can’t make the transition [to net zero] depend on that, as time is of the essence.”

Gernot Wagner, of Columbia Business School, warns of the distractions of radicalism: “It’s tempting to want to stick it to the man. We instead need to stick it to carbon. Sometimes the two are one and the same, often they are not. Inequality is a real and present problem for all sorts of reasons. If tackling wealth inequality is the most expedient way to cut carbon, I’m all for it. But we can’t delay climate action even further for the false hope of solving all the world’s other ills.”

But Avinash Persaud, adviser to the prime minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, says: “Trying to solve the climate crisis as if inequality doesn’t matter won’t work. The only workable solutions are those that show some recognition of contributions from within and between countries that caused the problem.”

Photograph: Johnny Miller