How big are the fires burning in Australia’s north? Interactive map shows they’ve burned an area larger than Spain

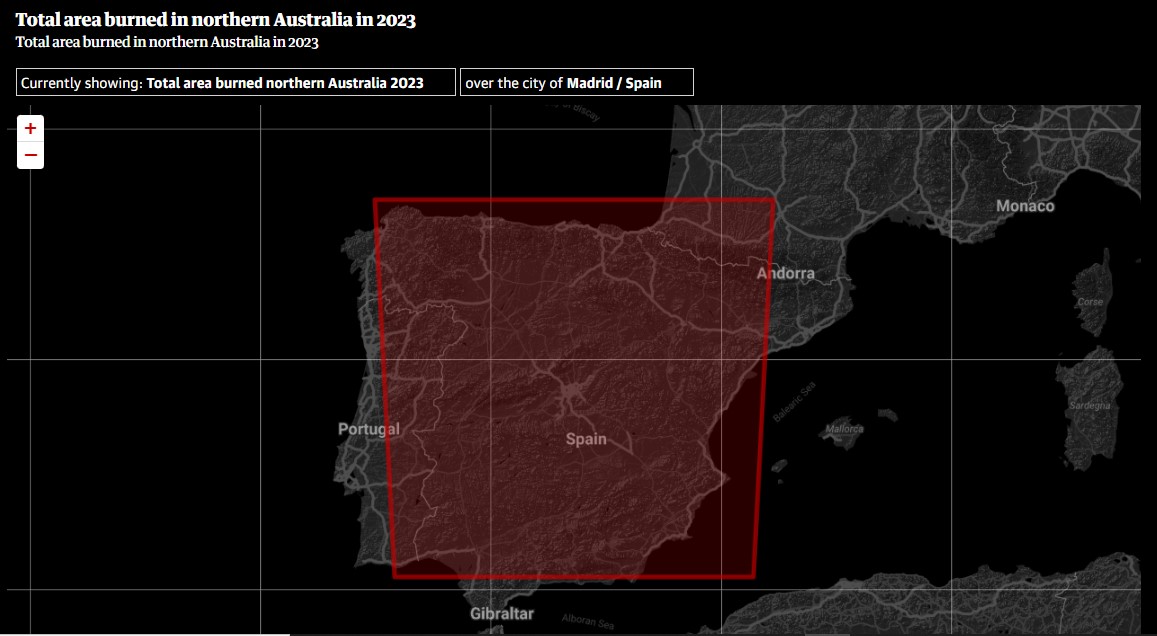

Huge bushfires have burned a significant amount of northern Australia in recent months, with the collective area burned larger than many countries, including Spain.

Experts say the massive fires are primarily due to a higher-than-average fuel load built up over the recent wet La Niña years, with an invasive grass species also contributing to more intense burns.

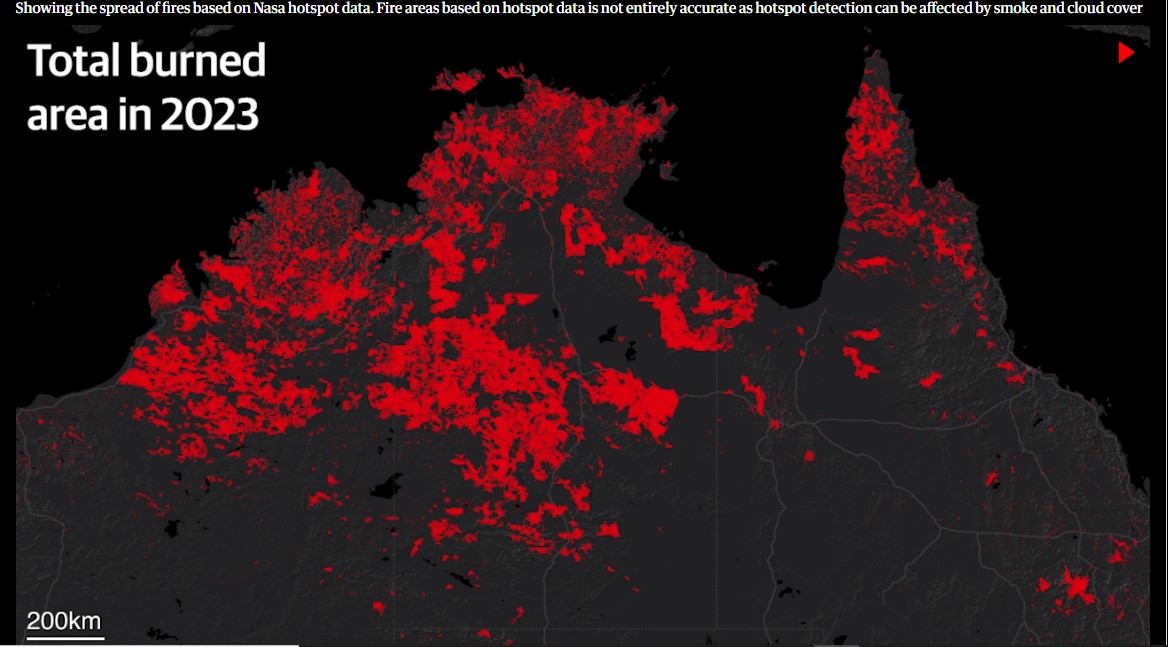

According to estimates of fire area based on satellite hotspot detection, more than 610,000 sq km have burned in 2023 across northern Australia. This is an area larger than many countries, such as Spain, Thailand and Cameroon.

Fire is common in the northern regions of Australia, particularly the tropical savanna areas of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland where regular burns are an integral part of the ecology.

Here, you can see the extent of fires animated from the start of September, based on Nasa hotspot data. That is followed by the total burned area for fires for all of 2023, based on North Australia and Rangelands Fire Information (Nafi) data:

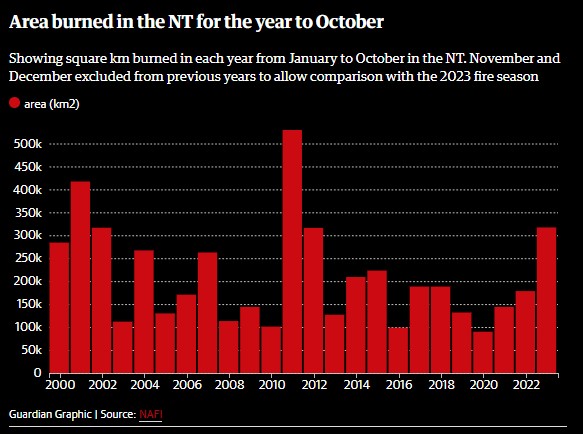

In the Northern Territory, some 310,000 sq km have burned up to the end of October. According to an analysis of Nafi data by Guardian Australia, this is the third largest fire year for the NT since 2000, with only 2011 and 2001 having larger areas burned:

In the Northern Territory, some 310,000 sq km have burned up to the end of October. According to an analysis of Nafi data by Guardian Australia, this is the third largest fire year for the NT since 2000, with only 2011 and 2001 having larger areas burned:

Dr Rohan Fisher is a fire scientist at Charles Darwin University and has spent much of his career mapping and monitoring fires in northern Australia. He says the scale of fires this year has been astounding, in large part due to the cyclical El Niño-La Niña weather cycles, where heavy rain in La Niña years results in increased growth of vegetation which then increases the fuel load for subsequent fires as the plants dry out.

“In the desert, fire and water are intimately linked,” he says.

“The La Niña cycles are linked to these massive fuel load events … for example the largest previous fire event … in 2011 were around 400,000 sq km. So that was massive.”

However, despite these cyclic weather patterns, the scale and intensity of recent fires is not normal, Fisher says.

“The fact is that where we see good fuel management of these desert landscapes, we don’t see fires at this scale,” he says.

“So what we’re seeing with the scale of these fires is a direct result of the dispossession of Indigenous land managers from their land.

“You look back, even 60 or 70 years ago, across much of the desert country where there were still people, you had these incredibly complex fuel load mosaics. Historically, if you go back 50,000 to 60,000 years, there would have still been the same cyclic fuel load cycles, but we would never have got fires of this sort of size.”

Fisher says that prior to the current fires, Indigenous rangers conducted management burns across 23,000 sq km in an unprecedented collaborative effort. Satellite hotspot data shows this management has been effective in the regions it was used, he says.

“When you look at [the fires] in relation to where there has been fuel load reduction, over a two, three or four-year period, we can see those fires have been controlled.

“For me, it’s pointing to the fact that there needs to be more investment in this incredibly large landscape scale fire management and desert country, across Australia at the heartland of this country.

“You need to continue that work to put fire back into country to have that sort of healthy country. And the work that’s been done is incredible, but it points to the need for more concerted support for that work, because the work that they did do was very effective.”

The Albanese government says it recognises the importance of Indigenous rangers, and has made a $1.3bn commitment to double their number from 1,900 to 3,800 by the end of the decade. It has promised to establish 10 new Indigenous protected areas managed by First Nations groups.

Another issue at play with the current fires has been the spread of invasive buffel grass in arid areas.

Originally introduced as pasture for grazing and to reduce erosion, buffel grass has spread widely across central and northern Australia over the past 30 years, and poses large risks to biodiversity in these regions. While it is considered a valuable resource for pastoralists, it also has changed the behaviour of fires in arid areas.

Researchers say because buffel grass grows faster and thicker than many native plants, it can fuel more intense and more frequent fires.

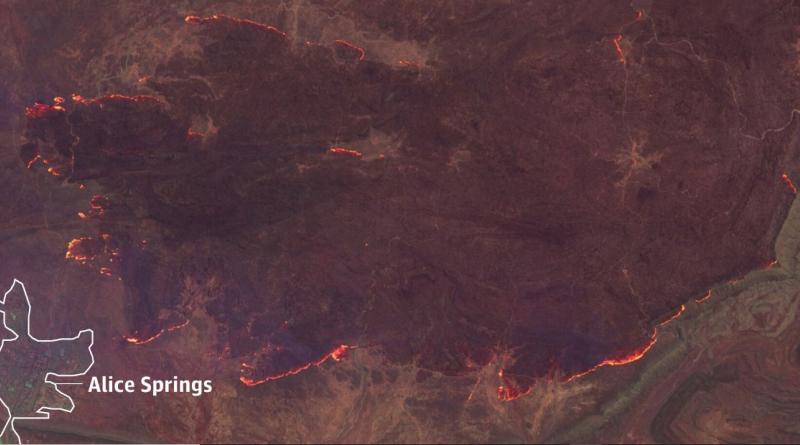

In August of this year, buffel grass was implicated in large fires near Alice Springs, and similarly in 2019. On Wednesday, nearly 40 organisations from across central Australia called on the NT government to declare the grass a weed and acknowledge the devastating effects it has on landscapes, the economy, health and culture.

Fisher says buffel grass is “fundamentally changing the the ecology of those landscapes”.

“Buffel grass [results in] a greater amount of fuel generally,” he says.

“It goes to places and allows fire to move through country where probably it wouldn’t normally because there’s this massive continuous fuel load, and after fire it grows back very quickly.”