Recent fires have been a triggering reminder of previous disasters. Our resilience is being tested yet again

Until governments engage with and provide more funding to the people under threat, we will always be playing a dangerous game of catchup

Some pretty weird and funny things happen in the chaos and stress of dealing with a bushfire that threatens our property on a day the power grid goes down. Like the text from your partner, who is on ember watch at her elderly mum’s home, that pings when you’re outside hosing down the front of the house and watching the flames on the ridge 600 metres away. “Put the banjo in the car and get the flute from the study.”

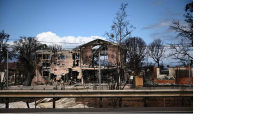

Tension-relieving humour aside, none of this is at all funny. It’s not yet three years since we watched at 5am on New Year’s Eve the massive fire burning through the two farms opposite us at high speed. We didn’t know then that it had claimed four lives, destroyed more than 400 houses and a third of the Cobargo village.

It’s not funny that the local grid went down, cutting power and some communications, even before the fire warning was issued.

It’s not funny waking up on Wednesday morning after two hours of sleep to the awful sound of your farmer neighbours shooting sheep and cattle injured in the fire and contemplating how these two lovely people with three young kids are going to come back from the second devastating fire to come through their property in under three years.

It’s not funny feeling the visceral tension of people in Cobargo and Bermagui, many of whom are still trying to rebuild their lives, homes and properties, not three years since the surrounding area was devastated by the 2019 New Year’s Eve fire.

And it’s certainly not funny that it’s early October, knowing that a fierce and unpredictable summer is ahead of us and that, despite valiant efforts, we are still not ready for what’s coming at us.

We have a fire plan, developed with the assistance of our closest neighbour and bushfire expert, Bruce Leaver. With his help, we’ve done extensive prepping on our bush block to reduce our risk and improve our chances of surviving a bushfire. We have an action plan that’s been honed over five close calls in 2019 and now through this one.

We’ve educated ourselves about the area we live in, on the edge of two dairy farms, surrounded by national park and state forest. We know about wind cycles, weather maps, fire-resistant plants that slow the speed of a fire, cool burning, header tanks and gravity-fed watering, roof sprinkler systems, fire pumps, generators, hoses and hose fittings, water tanks, how the Rural Fire Service operates and what its priorities are.

But we know that many people don’t have access to a local expert, or simply don’t have the time or the resources to do the work necessary to protect themselves and their properties. Time is scarce for people with family and work responsibilities. Many people don’t have the physical capacity to clear undergrowth or get up on a roof to clean gutters, and buying in help is not cheap.

And what of those in big cities who don’t realise that they too are under threat and haven’t thought they might need a fire plan?

As a country, we haven’t fully risen to the challenge of adapting our behaviour in the face of a growing and intensifying threat and we have not fully confronted the costs of living in a more uncertain climate.

But if we accept that the climate crisis is a fact and that living with the threat of disaster is the new normal, then we all need to start adapting.

Prepping is not easy; it takes time and it can be expensive. It’s already clear to us that we need to provide massive public and private sector support to directly assist communities and individuals to get ready for disasters.

In the Cobargo area, we are putting in place some very concrete adaptive measures. We now have four buildings with stand-alone solar-powered systems. A proposed community microgrid will ensure the village will remain powered in the event of the collapse of the grid or a deliberate decision to turn off the power to reduce risk during extreme weather.

Following the black summer bushfires, we set up a community access centre to address shortfalls in relief and recovery service delivery. Small neighbourhood disaster response teams have sprung up, equipped with UHF radios to maintain contact with neighbours.

This kind of focused grassroots community preparation work needs much more methodical support, provided through reliable, ongoing funding.

We need investment for resilient hard infrastructure, especially for place-based evacuation centres that double as community centres where we can do the strategic pre-disaster planning work as well as deliver an effective disaster relief and recovery response together with agencies.

We need investment in soft infrastructure, connecting communities through festivals, the local agricultural show, art, dance, morning teas. Sitting in scenario planning workshops might be a big part of readiness, but we need some fun in our lives as well.

For many, the Coolagolite fire has been a triggering reminder of what we endured in 2019-20. Our resilience is being tested yet again. Providing meaningful support to ensure that we can sustain our resilience in the face of more frequent disasters requires governments to engage directly with regional communities in a deep and frank conversation about adaptation to climate change.

Governments and the private sector need to acknowledge and be willing to pay for the real costs of rapid adaptation measures. Otherwise the burden of ensuring communities are disaster-ready and able to cope with the aftermath will continue to fall on groups like the RFS. The RFS does a magnificent job but it is too much to expect their volunteers to meet the ever-increasing needs.

Communities need to be seen as assets, not liabilities to be shipped out of the way the moment disaster strikes. You can fund as much research, inquiries, conferences and roundtables as you like. But until those holding the money engage with, listen deeply and provide more direct financial support to the actual communities under threat and who have lived experience, we will always be playing a dangerous game of catchup.