Deep-sea mining may push hundreds of species to extinction, researchers warn

New research sees two-thirds of mollusc types only found living by hydrothermal vents added to IUCN’s red list of endangered species

Almost two-thirds of the hundreds of mollusc species that live in the deep sea are at risk of extinction, according to a new study that rings another alarm bell over the impact on biodiversity of mining the seabed.

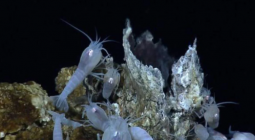

The research, led from Queen’s University in Belfast, has led to 184 mollusc species living around hydrothermal vents being added to the global red list of threatened species, compiled by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). While researchers only studied molluscs that were endemic to the vents (hot springs on the ocean floor), they said they would expect similar extinction risks for crustaceans or any other species reliant on the vents.

More than 80% of the oceans remains unmapped, unobserved and unexplored, and there is increasing opposition to deep-sea mining from governments, civil society groups and scientists, who say loss of biodiversity is inevitable, and likely to be permanent if it goes ahead.

“The species we studied are extremely reliant on the unique ecosystem of hydrothermal vents for their survival,” said Elin Thomas, the lead researcher. “If deep-sea mining companies want all the metals that form at the vents, they would remove all the habitat that the vent species come from. But the species have nowhere else to go.”

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body, is meeting in Kingston, Jamaica, to agree a route for finalising regulations by July 2023 that would allow the undersea mining of cobalt, nickel and other metals to go ahead.

There are at least 600 known hydrothermal vents worldwide, at depths of 2,000-4,000 metres, and each are roughly a third of the size of a football pitch. They act as natural plumbing systems, transporting heat and chemicals from the Earth’s interior in massive geysers, and they also help regulate ocean chemistry. In doing so, vast – and valuable – mineral deposits accumulate at the fissures. The heat from them, on the otherwise cold seabed, also makes them biodiversity hotspots, akin to coral reefs or tropical rainforests.

The paper was published in Frontiers in Marine Science and supported by Ireland’s Marine Institute. The scientists examined the regulatory framework and regional management objectives at each site, as well as exploratory mining licences.

Of the 184 species assessed, 62% are listed as threatened, many in the territorial waters of countries that have granted deep-sea mining licences, such as Japan and Papua New Guinea. Only 25 species are fully protected from deep-sea mining by local conservation measures, such as in the Azores and Mexico.

The extinction threat was worst in the Indian Ocean, where every species was listed as threatened and 60% as critically endangered, and where many mining exploration licences have been issued by the ISA.