The ocean is becoming more stable – here’s why that might not be a good thing

If you’ve ever been seasick, “stable” may be the last word you associate with the ocean. But as global temperatures rise, the world’s oceans are technically becoming more stable.

When scientists talk about ocean stability, they refer to how much the different layers of the sea mix with each other. A recent study analysed over a million samples and found that, over the past five decades, the stability of the ocean increased at a rate that was six times faster than scientists were anticipating.

Ocean stability is an important regulator of the global climate and the productivity of marine ecosystems which feed a substantial portion of the world’s people. It controls how heat, carbon, nutrients and dissolved gases are exchanged between the upper and lower layers of the ocean.

So while a more stable ocean might sound idyllic, the reality is less comforting. It could mean the upper layer trapping more heat, and containing less nutrients, with a big impact on ocean life and the climate.

How the oceans circulate heat

Sea surface temperatures get colder the further you travel from the equator towards the poles. It’s a simple point, but it has enormous implications. Because temperature, along with salinity and pressure, controls the density of seawater, this means that the ocean surface also becomes denser as you move away from the tropics.

Seawater density increases with depth too, because the sunlight that warms the ocean is absorbed at the surface, whereas the deep ocean is full of cold water. The change in density with depth is referred to by oceanographers as stability. The faster density increases with depth, the more stable the ocean is said to be.

It helps to think of the ocean as divided into two layers, each with different levels of stability.

The surface mixed layer occupies the upper (roughly) 100 metres of the ocean and is where heat, freshwater, carbon and dissolved gases are exchanged with the atmosphere. Turbulence whipped up by the wind and waves at the sea surface mixes all the water together.

The lowest layer is called the abyss, which extends from a few hundred metres depth to the seafloor. It’s cold and dark, with weak currents slowly circulating water around the planet that remains isolated from the surface for decades or even centuries.

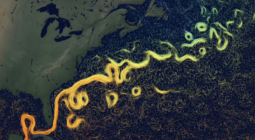

Dividing the abyss and the surface mixed layer is something called the pycnocline. We can think of it like a layer of cling film (or Saran Wrap). It’s invisible and flexible, but it stops water moving through it. When the film is ripped into shreds, which happens in the ocean when turbulence effectively pulls the pycnocline apart, water can leak through in both directions. But as global temperatures rise and the ocean’s surface layer absorbs more heat, the pycnocline is becoming more stable, making it harder for water at the ocean’s surface and in the abyss to mix.

Why is that a problem? Well, there’s an invisible conveyor belt of seawater which moves warm water from the equator to the poles, where it’s cooled and becomes more dense and so sinks, returning back to the equator at depth. During this journey, the heat absorbed at the ocean’s surface is moved to the abyss, helping redistribute the ocean’s heat burden, accumulated from an atmosphere that’s rapidly warming due to our greenhouse gas emissions.

If a stabler pycnocline traps more heat in the surface of the ocean, it could disrupt how effectively the ocean absorbs excess heat and pile pressure on sensitive shallow-water ecosystems like coral reefs.

Increasing stability causes a nutrient drought

And just as the ocean surface contains heat that must be mixed downwards, the abyss contains an enormous reservoir of nutrients that need to be mixed upwards.

The building blocks of most marine ecosystems are phytoplankton: microscopic algae which use photosynthesis to make their own food and absorb vast quantities of CO₂ from the atmosphere, as well as produce most of the world’s oxygen.

Phytoplankton can only grow when there is enough light and nutrients. During spring, sunshine, longer days and lighter winds allow a seasonal pycnocline to form near the surface. Any available nutrients trapped above this pycnocline are quickly used up by the phytoplankton as they grow in what is called the spring bloom.

For phytoplankton at the surface to keep growing, the nutrients from the abyss must cross the pycnocline. And so another problem emerges. If phytoplankton are starved of nutrients thanks to a strengthened pycnocline then there’s less food for the vast majority of ocean life, starting with the tiny microscopic animals which eat the algae and the small fish which eat them, and moving all the way up the food chain to sharks and whales.

Just as a more stable ocean is less effective at shifting heat into the deep sea and regulating the climate, it’s also worse at sustaining the vibrant food webs at the sunlit surface which society depends on for nourishment.

Should we be worried?

Ocean circulation is constantly evolving with natural variations and human-induced changes. The increasing stability of the pycnocline is just one part of an extremely complex puzzle that oceanographers are striving to solve.

To predict future changes in our climate, we use numerical models of the ocean and atmosphere that must include all of the physical processes responsible for changing them. We simply don’t have computers powerful enough to include the effects of small-scale, turbulent processes within a model that simulates conditions over a global scale.

We do know that human activity is having a greater than expected impact on fundamental aspects of our planet’s systems though. And we may not like the consequences.

7 April 2021

THE CONVERSATION