Water Becomes the New Land for Solar Plants in India.

Utilities and companies in India are planning hundreds of megawatts of solar projects floating on water bodies as it becomes increasingly difficult to secure large parcels of land.

“Land availability is a challenge already, and it will become a bigger issue,” said Ayyub Kunnanolli, executive engineer at the Kerala State Electricity Board. The state utility has constructed one of India’s largest operational floating plants – a 0.5-megawatt installation in the reservoir contained by the Banasura Sagar dam.

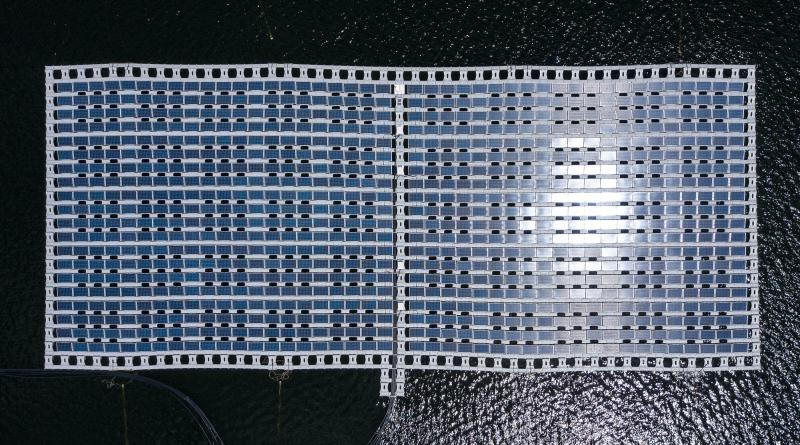

The plant stands on a hollow ferro-cement floater that almost replicates land on water. Last month, not a ripple was felt as utility executives – in batches of 20 people – stood on the floating solar platform to take a look at the solar installation, which survived the devastating 2018 floods in the state.

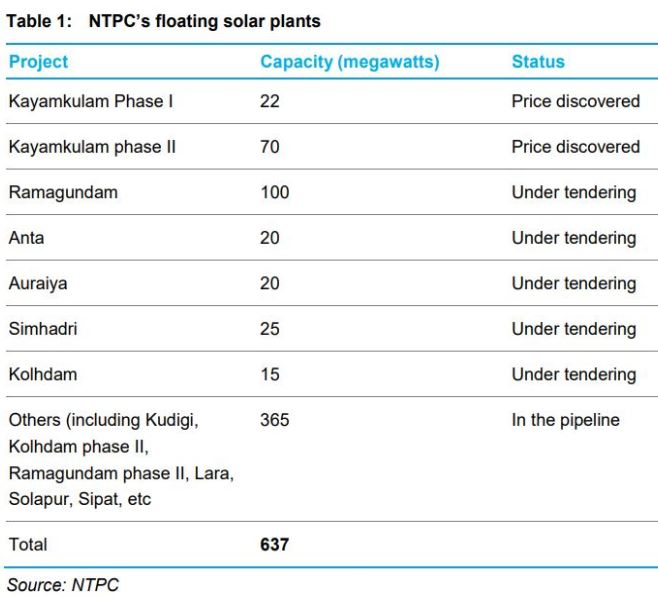

NTPC Ltd., India’s largest power generator, aims to take the lead in floating solar plants. The water reservoirs at its coal-fired plants serve as ready locations for floating solar panels. And putting a structure on top of the water also helps to prevent evaporation of the precious resource.

The company has about 650 megawatts of floating solar projects in the pipeline, according to a presentation NTPC made to the group visiting the Banasura Sagar project.

“Dams and other stagnant water bodies are the low-hanging fruit for floating solar plants. It is an ideal combination of yellow and blue to give green power,” said Vivek Jha, the co-founder of Yellow Tropus, a company providing engineering and construction services for floating solar plants.

It is building its first megawatt-scale floating plant for Renew Power Ltd. at Visakhapatnam in South India, and sees demand picking up pace.

The potential of India’s floating solar market is also appealing to Norway’s biggest utility, Statkraft AS, which announced the construction of its first floating solar plant earlier this year, in Albania.

“We are seriously exploring floating solar opportunities in India,” said Krishnan Rajagopalan, director at Statkraft Solar Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

The company has decades of experience in hydro-electricity, and believes it can take advantage of that knowhow for floating solar projects. These could offer better margins than conventional solar projects, which have seen intense competition erode margins.

There are over 1.3 gigawatts of floating solar plants globally, according to a report from BloombergNEF. China accounts for 85 percent of these installations, followed by Japan and South Korea. India is set to be one of the top four countries for floating solar, according to BNEF.

“Floating solar plants can help move India closer to its ambitious installation target for 2022,” said Rohit Gadre, BNEF’s solar analyst for India. India aims at 100 gigawatts of solar power installations by 2022, against the current level of about 27 gigawatts.

Higher generation

Generation from floating solar plants tends to be 6-10 percent higher than from land-based, according to industry estimates. There is also an efficiency argument for such projects: they enable better utilization of existing transmission infrastructure.

Waaree Energies Ltd., a local maker of solar panels, is excited by the burst of activity seen in the last few months, and sees a good market for its “floato-voltaic” solution.

“We are bidding for many projects. There aren’t too many technical challenges here,” said Waaree director Sunil Rathi. The incremental cost of a floating solar plant, compared to a ground-mounted solar plant, has already come down from 100 percent to 50 percent, he added.

Waaree is building a 1-megawatt floating solar plant for NTPC at Surat in Gujarat.

Large reservoirs are ideal places for a 50-megawatt or a 100-megawatt floating solar plant.

Ronnie Khanna, senior energy sector specialist at German development bank KfW, made a case for incentive tariffs for the first batch of floating solar plants, to account for benefits like prevention of evaporation and the absence of people displacement issues. “Solar plants on water bodies hold a huge potential to meet our rapidly growing energy demand, without competing for scarce land. In addition, floating solar plants prevent the evaporation of a second scarce resource: water. These plants should be encouraged,” he said.

Challenges

Depending on who you speak to, the biggest challenge identified is either the design of the plant – “It cannot be a one-size-fits-all, and needs to be customized after a proper bathymetric study,’ said Yellow Tropus’ Jha – or in the execution of the project: “I think the execution challenge is much more than the design challenge,” said Waaree’s Rathi.

There are several tricky decisions awaiting a developer: Should the floater be anchored to the ground or tethered to the shore? Should the transformer package be on the floater or on shore? What is the best way to prevent any leakage of current to the water?

Kunnanolli said one of the biggest challenges he has faced with the Banasurasagar plant is bird poop. A floating plant in a large body of water is an inviting halt for overflying birds, and removing dried poop without damaging the panel is quite a task.

Challenges notwithstanding, there is an expectation that the cost of power from floating solar will be lower than that from conventional solar sooner rather than later. “Naturally. It has to be. Land cost will go up as availability goes down. Float cost will [ultimately] become lower than land cost,” said KSEB’s Ayyub.

Tariff is key

A floating solar auction of 150 megawatts on the Rihand reservoir by the state-run Solar Energy Corp. of India in November last year had a ceiling tariff of 3.32 rupees (4.7 cents) per kilowatt-hour. Indian business conglomerate Shapoorji Pallonji Group bagged 50 megawatts in the auction at a tariff of 3.29 rupees per unit. Since there was only one bid for the balance capacity, the tariff will need to be approved by the state power regulator.

Tariff is the key here. Buyers of power – the distribution companies – have a limited appetite for pricey power. Indian utilities have been cancelingcompleted auctions if the tariff discovered veered too far from the record low of 2.44 rupees per unit of solar power. Tariffs of floating solar will need to be competitive to find takers in the market.

“If the buyers of power from floating solar quote a ceiling price, it will be part of the tender too,” said Sanjay Sharma, SECI general manager.

“A competitive tariff is the key [for floating solar], but it should not be at the cost of quality,” said Khanna, as he, like most other industry officials, made a case for setting standards for floating solar plants.

Meanwhile, SECI has moved one step ahead, with a tender for a 20-megawatt floating solar plant with 60 megawatt-hours of storage at Lakshadweep islands. “We want to store solar so that it can be used to meet peak demand,” said SECI’s Khanna. The deadline for bid submission is May 2, 2019.

Clients can read the full report on floating solar projects here.

7 May 2019

BLOOMBERG NEF