Solar CEO: ‘Heating electrification is one of the biggest mistakes of the energy transition’.

Wind and solar photovoltaic are way too small to cope with Europe’s massive demand for heating, especially in winter, says Christian Holter, who calls for allocating scarce renewable energy resources to economic sectors where they can bring the most in terms of carbon reduction.

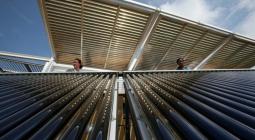

Christian Holter is the CEO of SOLID, an Austrian company specialising in large-scale solar thermal energy plants. He spoke to EURACTIV’s energy and environment editor, Frédéric Simon.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

- Meeting the EU target of growing renewables in heating and cooling by 1.3% annually “will be a really tough task” even though the target is “insufficient” to meet the Paris climate goals

- This is because oil, gas and coal heaters are easier to install than renewable alternatives – and the upfront costs are lower

- It “makes no sense” to bring electric power into heating, because winter demand for heat is 5 to 10 times bigger than the entire electricity system, which won’t be able to cope

- And considering only 30% of electricity is currently coming from renewables, electricity cannot reasonably be considered as a backbone for the heating sector in Europe until it becomes fully decarbonised

- That leaves biomass, solar thermal and – to a lesser extent – geothermal as the main renewable alternatives in the heating sector

- But even there, careful allocation of renewables is necessary, with biomass better suited for industrial heat purposes where high temperatures are needed and solar thermal more suitable for space heating

///

Fossil fuels – coal, oil, and gas – currently represent 75% of the demand for heating in Europe. Are renewable energy alternatives now mature enough to take over and eventually eliminate fossil fuels from this sector?

This dominance of fossil fuels has historic reasons. Oil, gas and coal are easy to use and install. And renewables, from a technical point of view, could certainly do more but they are acting in a very conservative market where transitions aren’t happening fast.

So you’re saying renewables are more expensive and more complicated to install?

To install a renewable heating water system, you need more knowledge than to install a gas boiler. That’s a matter of fact. You need more skills and knowledge. People have learned how to work with fossil fuel installations over the last 50 years, and despite all the education efforts, this old mindset is still very much present. Customers, suppliers and consultants are quite conservative and they’re talking more about transitions rather than really doing it.

So you’re saying there is still some way to go before renewable alternatives become as cheap and easy to use as fossil fuels.

I wouldn’t say fossil fuels are cheap because it depends on the perspective. If you take a long-term perspective, I am convinced that renewables are competitive. The challenge is the upfront cost of installation, where renewables are often more expensive.

This is true especially for private households, which cannot always put the money upfront for a new installation that will pay off over a decade or more. But for cities and local authorities, as soon as you take a 20-30 years perspective, renewables are competitive, definitely. When you take a life-cycle perspective, renewables look much more attractive financially.

The EU adopted an objective to grow renewables in heating and cooling by 1.3% every year until 2030. Some claim this is too ambitious, others not enough. What is your view?

If you want to fully decarbonise the energy system by 2050, 1.3% per year is definitely not sufficient. On the other hand, when you look into the changes that meeting this target will require in terms of legislation, education and adaptation at the local level, and new installation capacity – and I personally know all these hurdles – then you realise it will be a really tough task.

Why is this? What are the obstacles?

There is the educational part, which I already spoke about. Another part is that financing for long-term investments is becoming more and more difficult. And I experienced that personally because we do a lot of heat purchase agreement with solar thermal.

It used to be a lot easier to raise the capital than today. And today people in the financing world much prefer to have short returns on investments instead of a financial exposure over a longer period, which they perceive as being more risky. So their preference goes to investments with returns of 3 to 5 years.

For renewable energy infrastructure, you need to turn this the other way round and bring a 25 or 30-year perspective. And if I recoup my investment in 15 to 20 years, it will be great. This is where the development of the finance world and the needs for sustainable development go in totally opposite directions.

Mass-scale electrification is expected to revolutionise the heating and cooling sector. Is 100% electrification desirable? What are the limits of electrification in this sector?

I think electrification of the heating sector is one of the biggest mistakes happening in the energy transition. I do not see a sensible way to put all the heating demand on electric production and distribution – on top of electric mobility.

Just look at the rate of electrification. In most European countries, electricity covers only about 20% of total energy consumption whereas heating and cooling takes up about 50% of total final energy use. That means we have a demand factor for heating and cooling which is about 2.5 times higher than the current rate of electrification.

And in winter, the demand for heating and electricity is 5 to 10 times higher, at least in Central and Northern Europe. And I don’t see any sustainable electricity source which could balance the heating needs we have in those places.

There are major advances being made in batteries and demand-side response, and those are expected to gather momentum in the coming years. Isn’t that going to shave off the peak demand for electricity in winter?

No, because the heating sector is so much bigger. The electricity system simply couldn’t keep up, especially when you consider that only 30% of electricity today is sustainable, coming from renewable energy sources.

Excessive wind power can be used to support heating during the winter period here or there. But I don’t think electricity can reasonably be considered as a backbone for the heating sector on the European scale. Certainly not if you want to meet that demand with renewables.

What kind of share for electricity would you consider reasonable in the heating sector?

If electricity goes into heating, it must come from renewable energy sources. Otherwise, we would have to burn coal or nuclear for heating, which makes no sense.

First, we would need to triple or quadruple the share of renewables in electricity so that it becomes green. And then we could start a discussion about putting that electricity into heating. But until this is done, electrifying the heating sector makes no sense because it would be running on coal and nuclear.

Now, let’s imagine we manage to quadruple renewable electricity production in winter. What are the available options to do this? Hydro is already being used close to its maximum potential so there isn’t much to be expected there. Solar PV doesn’t help us very much in winter.

So the only renewable source left is wind energy. But if you want to meet heating demand with wind, you need to multiply the wind sector by a factor of 10 or even more. And building so many more windmills won’t be easy because new locations for onshore wind farms are not always socially acceptable – some will be rejected by people.

Add to that all the electric cars which are coming in the next few years – they need to be running on renewables otherwise they can’t be considered sustainable. So I really don’t see sustainable electricity meeting any significant part of heating demand in the coming years. This can be envisaged maybe in sunny regions or in the summer, to meet the demand for cooling or hot water.

So what is the reasonable share you see for sustainable electricity to meet heating demand in Europe?

It’s hard to guess, but I would say below 15-20%, for sure.

Now, looking at the possible renewable alternatives for heating and cooling, there are many possibilities ranging from bioenergy to solar thermal and electric heat pumps. What in your view are the most promising ones? Do you believe there will be a winner-takes-all situation on this market?

There won’t be a winner-takes-all, for sure. There needs to be a mix because different sources of energy can contribute to different things. In winter, some renewables like biomass and biogas are well suited to meet peak demand for heating, electricity and hot water for instance. And other sources like solar thermal in combination with long-term hot water storage are convenient for baseload and peak load in heating.

So at the end of the day, a new heating system needs to combine different renewable energy sources together in a smart way in order to meet the demand for heating and hot water.

Which of those renewable alternatives would you single out as the main ones in the coming years?

- Bioenergy for sure – especially for medium-sized district heating systems installed in some villages or for individual households.

- I see also a big potential for solar heating on a city level, combined with seasonal storage. This is a very competitive technology and my guess is that it will be the big winner in the next 10 to 20 years.

- I see a little potential for biogas because it’s very flexible and can be used to cover peak demand, together with cogeneration.

- There are some places where you can do geothermal but geographically it’s quite limited.

I think these are the main carbon-free heat sources we can have in the future.

That means we need to be very careful when selecting the fuels going into certain applications. Forindustrial uses, where you need high temperatures around 800-1,000°C, it’s very clear that you need to burn something. And this is where biogas and biomass can play a role – because they can provide those kinds of temperatures.

But when you need to simply heat a room to 20-23°C, a low-grade heat is sufficient. And here, you can use a lot of other things. So I expect there will be quite some change there in the coming years. This is why I believe the biomass which is currently used a lot in the household heating sector, in the coming years should be used more in the industrial heat sector – to replace natural gas or oil.

And that means the demand for space heating can be largely met with solar thermal.

Do you believe a ban on fossil fuel boilers should be introduced to accelerate the shift to clean heating?

A ban surely will booster market success. Coal in Europe is declining anyway. But we need more drivers for sure to bring more renewables into areas currently covered by the oil and gas sectors.

And the key to a global success will be our ability to export outside of Europe. Because worldwide, honestly, we are a small player. So our approach in Europe must be geared towards growing our exports on a global scale, in order to bring prices down.

Are there renewable alternatives that can be brought to industrial scale?

The main challenge today is that we have millions of individual units. And the limit I see on renewable heating sources is related to size and storage. The challenge we are constantly confronted with in the heating sector is how to match demand and supply – which is linked to storage. And small-scale energy storage is expensive. It’s a real limit for renewables – the smaller the installation, the higher the cost.

Larger systems like district heating systems are much easier to implement renewables because you can scale up and bring the costs down. But for the small domestic installations, it’s different, and much more expensive.

Replacing millions of old fossil fuel boilers scattered around Europe is going to be a massive task that will probably take decades and cost a lot of money. How can this whole process be speeded up?

One important thing is to have the right policy guidelines. And it’s clear that, after a certain point, there should be no new installations of non-sustainable heating systems. Another thing is to support the development of the industry – on the manufacturing side as well as the installation and maintenance side.

And there are some good examples. In parts of Austria for instance, they banned the installation of all new fossil fuel heating systems. So connecting to district heating is fine, installing a biomass or solar system is fine, but you’re not allowed to install new gas boilers anymore, they refuse that.

And that will allow to decarbonise the heating system over time. Remember that a boiler may last for 20 or 30 years so it will take time before all these boilers are replaced. But in the mid to long-term, it certainly helps.

That is pretty much what the EU recommended in the renewable energy directive – a slow and gradual uptake. So you’re saying the EU got it right or do you believe more should be done?

In the heat sector, the big picture of the energy transition is not fully clear yet. Leaving fossil fuels out is a good thing, but there is no clear path ahead for the long-term conversion of the heating sector. And as a result, there is a lot of confusion about what to do and where to set priorities.

At this point, Europe needs a clear vision for the heating sector which is driven by the recognition that our renewable energy resources are limited. Lobbyists will always tell you they have the silver bullet but they don’t. So policymakers should try to map the demand for heating and cooling in 2030, 2040 and 2050, and then look at the renewable technologies that are available and allocate them in the smartest way. For sure energy efficiency has to be the starting point. And then you have to align the specific renewable technologies with the specific demands that people have.

And today, there are too many lobbyists saying they have the solution. But in the heating sector, you simply cannot take a single interest point of view. To decarbonise the heating sector, Europe will need a combination of solutions that meets the specific needs of its diverse geography.

*This article is part of our special report Decarbonising heat

16 April 2019