Ramaphosa’s $11bn climate fund, or, how the smart money could turn Mpumalanga into the envy of the world.

In a nation that’s become used to operating in the shadows, sometimes even the mention of sunlight can be met with disbelief. But sunlight is what President Cyril Ramaphosa offered in his pledge to UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres during the climate summit in New York — R160-billion worth, for a plan that could turn the Mpumalanga coalfields into one of the largest renewable energy generators on Earth.

If there’s any reason to believe that we’re about to embark on a massive industrialisation drive, a project that will drastically reduce our carbon emissions and deliver long-term energy security, it’s that the economic alternatives are too dark to contemplate.

For a moment it was light, then it was dark again.

On 24 September 2019, when most South Africans were embracing the public holiday as a welcome relief from the news, President Cyril Ramaphosa sent a statement to United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guterres that may have been the best news of the year. The pledge, South Africa’s core submission to the UN Climate Action Summit in New York, made reference to an $11-billion renewables funding facility that would represent “the largest climate finance transaction” the world had ever seen. Two days later, all mention of the deal had been excised from the government’s online version of the statement.

None of the inside sources approached by Daily Maverick were willing to say why, but speculation from a less-connected source was that the deal’s “ownership” was still being worked out — whose plan it was, in other words, and how it would be presented to the South African public.

It was an explanation that made sense, mainly because a Bloomberg report published the week before had cited Meridian Economics, a Cape Town-based consultancy, as the brains behind the initiative. This wasn’t just bad optics; allegedly, it also wasn’t true.

“All of the thinking comes out of the Eskom Sustainability Task Team,” Stellenbosch University’s Mark Swilling told Daily Maverick. “The $11- billion fund that the president refers to [in his UN pledge] forms part of the recommendations that the task team made directly to him.”

And so, barely out the gate, we were neck-deep in the politics, wading through the vagaries of a statement made and retracted, the apparent misattribution of a journalist, the secrecy of a presidential task team, and the sheer weight of R160-billion in never-before-seen “climate finance”. Given that this was all to do with the creation of an entirely new energy sector, the imagery of things flickering in and out of focus seemed apt.

As for Swilling, who also happened to be deputy chairman of the Development Bank of Southern Africa — and who had co-authored the highly influential Betrayal of the Promise report on State Capture — there was arguably no one better placed to steer us back towards the light. Hours after Ramaphosa’s statement went public, Swilling’s take was summed up in a tweet: “The clearest commitment ever made to the South African energy transition. I’m blown away!”

The dark, of course, had been constellating around Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe, South Africa’s resident cheerleader for coal. Seeing as the fossil fuel was the “single-largest source of global temperature increase,” according to the International Energy Agency, “responsible for over 0.3°C” of the 1°C rise above pre-industrial levels, Mantashe’s love affair with the stuff was looking more fundamentalist by the day.

“If Mantashe only followed the numbers,” said Swilling, “he would realise that renewables are the cheapest option.”

By which he meant we should put aside the climate for a second and approach the problem using basic economics. From the point of view of the consumer, Swilling pointed out, coal cost R1.30 a kilowatt-hour in 2019 prices, renewables were tracking at around 60 cents — “if you did it at scale, you could probably bring that down to 55 cents” — and nuclear was anywhere between R1.70 and R2.80, as per the industry’s own latest report.

The nub of the matter, by Daily Maverick’s reading, was this: despite the fact that Guterres had recently placed South Africa in the company of climate rogues, denying the president a speaking part at the New York summit, Ramaphosa had drafted a statement that worked for the climate because it worked, first and foremost, for the South African economy.

“The mitigation challenge posed to South Africa is considerable,” the president declared near the top of his statement, after noting that he shared Guterres’s concerns about the escalating planetary emergency. “About 80% of our emissions are from our energy sector.”

Two paragraphs later, he added: “The rapid fall in prices of renewable energy technologies, coupled with our immense renewable energy resources, has created a massive opportunity for us to make this shift [towards a carbon-neutral future].”

Even though the paragraph about the $11-billion climate fund had been deleted from the online record, these lines — which did not get excised — were an astonishing departure from the government’s mealy-mouthed norm. But were they worth the paper they’d been printed on? Hadn’t the South African state, which emits more greenhouse gas than many of the oil-soaked nations in the Arabian Peninsula, duped its citizens about climate mitigation before?

The $3.75-billion World Bank loan for the completion of Medupi in 2010, which had introduced South Africa to the lie of “clean coal” and derailed a renewables drive that should have begun in earnest after the rolling Eskom blackouts of 2008, was an example that sprang to mind.

Then again, that was back before climate science had properly caught up with climate fact.

II.

On 22 September 2019, two days before Ramaphosa sent his letter to Guterres, Reuters put out a pieceheadlined, “Banks worth $47 trillion adopt new UN-backed climate principles”. On the eve of the summit, financial institutions including Deutsche Bank, Citigroup and Barclays had committed to shifting their loan books away from fossil fuels. Although critics argued that the banks could have gone much further by pledging to phase out financing for coal, oil and natural gas altogether, the resolution was a rare victory for the UN — by reneging on their commitments, the banks could be stripped of their signatory status, and thereby face reputational risk in a world that was rapidly waking up to the reality of global heating.

For South Africa, where “close to 75%” of the coal fleet would reach “end-of-life by 2040” — a fact accompanied by detailed graphs in the final draft of the Integrated Resource Plan of August 2018— the question posed by this trend was simple: how would the country find the funding to replace those plants? If the private institutions wouldn’t put up the money, it was a fait accompli that the big development banks wouldn’t either: not the World Bank, not the French Development Bank and not KfW, Germany’s development bank.

Also, in terms of the divestment pecking order, oil and natural gas were better off — when it came to coal,more than 100 of the world’s leading financial institutions had declared they would no longer be investing at all. On 26 September 2019, dealing a death blow to the “energy poverty” publicity campaign of the US’s largest coal multinational, the African Development Bank announced at the New York summit that it was “getting out” of the resource for good. As a cure-all for the energy needs of poor and developing countries, this was the strongest signal yet that coal’s days were done.

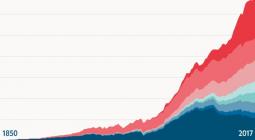

Meanwhile, global investment in new renewable capacity, already three times the amount invested in 2018 in new coal and gas, was all the evidence needed that wind and solar were colonising the terrain; on 29 September, in a deeply symbolic move, even the Saudi Industrial Development Fund would open applications for renewable energy projects.

Ramaphosa’s UN statement, in its original, non-censored form, demonstrated that the Eskom task team had fully assimilated the zeitgeist. For starters, the excised version contained the term “Eskom Sustainability Task Team” itself, right next to the phrase “Just Transition Transaction”. While Daily Maverick was unable to obtain a copy of the report that the task team had compiled for the president, we had no trouble obtaining second prize: details from a presentation that one of the team’s leading members, Dr Grové Steyn of Meridian Economics, had been carefully targeting since late July at activists and potential partners.

The all-important slide was headlined “A Just Transition Transaction”. Its purpose was to explain the “climate finance investment vehicle” — a choice of phrasing, given Ramaphosa’s pre-edited promise of an $11-billion “climate finance transaction,” that clearly wasn’t a fluke. Towards the bottom of the slide, after bullet points about the early decommissioning of ageing coal-fired power plants and moratoriums on new coal developments, the phrase “blended finance vehicle” appeared. Hardly a universe removed from the “blended finance facility” that was cut from the president’s pledge, its function was obviously to bring together “concessional financial support from funds with a climate mandate” and capital “from [Development Finance Institutions] increasingly unwilling to lend to traditional coal utilities”. Finally, at the bottom of the slide, there appeared the magic number: “R150bn+”. In other words, somewhere in the region of $11-billion.

Neither Steyn nor his colleague Emily Tyler, who had been quoted in the Bloomberg article on 16 September, were willing to speak to Daily Maverick — from all sources approached, the word was that political and financial negotiations had reached the pressure-cooker stage. But echoing Bloomberg and Steyn’s presentation, we confirmed that the plan was for the $11-billion to be split into two flows: the first to help pay off Eskom’s R460-billion debt, conditional on accelerated decommissioning of the utility’s current coal fleet; the second into a “Just Transition Fund” to secure employment for workers whose jobs might be lost.

To bring along the trade unions, a factor on which the success of the project would depend, it was always essential that this last issue got resolved. Here, to guide us through the complexities, Daily Maverickturned to Stellenbosch University’s Michelle Cruywagen, whose preliminary research had shown that roughly 40% of the 82,000 workers in the coal industry would retire “with pensions” in the next 20 years. As verified by sources close to the president’s proposal, at least half of the remainder would stay in “repurposed export-orientated coal mines,” implying that the coal industry would not be completely shut down. The rest, according to Cruywagen — between 20% and 30% — would be “trained for other industries, most likely renewables.”

And while Carol Paton would claim in Business Day on 30 September that the government had been “alarmingly remiss” about involving workers in the plan, stating that Ramaphosa had met Cosatu leadership to discuss it only once, Cruywagen would inform us of a grassroots initiative that suggested the unions weren’t sitting on their hands.

For months already, she said, the environmental NGO Groundwork and the policy research institute Naledi, whose directors included senior leaders from Cosatu, had been helping coal workers and affected communities in Mpumalanga to self-organise.

“They’re basically one community,” said Cruywagen, “because they depend on each other financially, they live together, they are directly impacted by the outcome of any government plan.”

At which point she cut to the chase: the fact that for these communities, as detailed in the “Deadly Air” court papers that named Ramaphosa himself as a respondent, the status quo was insupportable.

“With the health issues,” explained Cruywagen, “it’s children that are affected the worst, they’re the ones that get asthma and bronchitis from the coal plants. Thanks to the levels of poverty in the area, many people think they don’t have a choice. They think coal is the only way.”

III.

But of course there was another way, an economic alternative to the dystopian reality that would have the side effect of rendering the air breathable, the water drinkable and the future bearable — basically, exactly what it said every South African was entitled to in the Constitution, and yet rights that had begun to look for millions of citizens like utopian dreams. Which was perhaps why so few people were ready to believe it, why the plan was shifting in and out of focus, why hardly anybody who knew anything would talk.

Except for those few who did.

Said Swilling: “So if the transition fund that President Ramaphosa referred to can be used to fund the reindustrialisation of Mpumalanga around renewables, that could probably turn the region into one of the biggest renewable energy generators in the world. Sure, that’s a big if… but Mpumalanga is perfect for it, because it has grid capacity, unlike the Northern Cape.”

In a recent paper by Finnish academics titled “Pathway towards achieving 100% renewable electricity by 2050 for South Africa,” it was concluded that a renewables-based system was both achievable and the best policy option for the country. No new coal or nuclear plants were installed in the paper’s “least-cost pathway”, where hundreds of thousands of new jobs were projected by 2050.

“The results of our study indicate that a 100% renewable energy system is the least-cost, least-water intensive, least-GHG-emitting and most job-rich option for the South African energy system in the mid-term future,” one of the authors told Engineering News.

On the other hand, there were the consequences of business-as-usual, a cascade-effect of astonishing penalties that had been laid out in a report published in March 2019 (with funding support from the World Bank, French Development Bank and Development Bank of Southern Africa) titled “Understanding the impact of a low carbon transition on South Africa”.

“For as long as South Africa depends on coal and other commodities for a large part of its exports, the impact of climate change-driven transition on the country’s economy may be more dependent on the actions of our international partners than our domestic policy,” wrote Patrick Dlamini, DBSA’s CEO, in the report’s preface.

“For me, one of the most striking findings from this report is that South Africa faces ‘transition risk’ approaching R1.8-trillion ($125-billion) in present value terms if the world achieves a path consistent with the Paris targets. With much of this risk apparently due to fall on the public balance sheet, such transition risk could strain the public finances, jeopardise the sovereign credit rating and the government’s ability to pursue a progressive social agenda.”

In other words, while climate change was shifting the world economy on its axis, South Africa had a very narrow window in which to play catch-up.

With this in mind, Daily Maverick was able to confirm from various sources that the full cost of replacing coal with renewables would be around R2-trillion over a 20-year period. By the close of 2018, the renewable energy operational capacity of the Eskom grid was 3.96 gigawatts — the cost of generating those gigawatts was R209.4-billion, which was how much the renewables sector had attracted in private investment since 2010. Given that the coal plants marked for decommissioning in the 2018 draft IRP were responsible for just under 30 gigawatts, and making allowances for the moratorium on new coal plants that would no doubt be demanded, it amounted to an investment of roughly R100-billion a year for 20 years, at today’s prices.

Which sounded like a lot, until you considered that wind and solar were projected to attract a combined $9.5-trillion (R142-trillion) in global investment by 2050, way surpassing the growth trajectory of any energy source in history. The discount against the heavy grid infrastructure already in place across the legacy coal complex of Mpumalanga, which had the wind off the escarpment to make up for what it lost in solar capacity against the Northern Cape, was something for economists to figure out — as was the cost of failing to mitigate against air pollution, environmental degradation and climate collapse.

Then there was the factor known as “upstream industrialisation” — the knock-on effect for the broader economy that would arise from the imperative to make the grid “smart”. Industry expert Mike Levington,writing for this publication in 2016, noted that “the least-cost path… must also create the space for the establishment of renewable energy versions of Anglo, Billiton and Exxaro.” These would be the companies that installed and maintained the wind turbines and solar panels, the companies that manufactured or supplied the electronic components to hook into the grid infrastructure, the companies that consulted across the value chain — they would, in theory, hold the elusive promise of large-scale upskilling and employment.

Would people get rich? Probably, but not by fossil fuel standards, because nobody had yet figured out how to own the wind or the sun. As US author and climate activist Bill McKibben wrote in his most recent book: “That’s why Exxon hates solar: you put up a solar panel and the energy comes for free, which to the corporate mind is the stupidest business plan ever.”

The thing about Ramaphosa’s proposal, though, was that it wasn’t a business plan; it was an attempt to rescue the power utility and reignite the South African economy, comparable in scope and ambition to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal or, perhaps more accurately (since we’re talking about heads-of-state), Roosevelt’s New Deal. The long-term play was that the R160-billion, which would be placed into a special-purpose vehicle owned by National Treasury, would trigger the R2-trillion investment needed to replace coal with renewables, which would in turn trigger the upstream reverberations.

“This could be the biggest energy and industrialisation programme since 1994,” said Swilling.

As to the likelihood of it happening, within 24 hours of Ramaphosa submitting his statement to the UN, some strong signals began to emerge from the executive branch.

IV.

Before noon on 25 September, during one of his routine engagements with industry, all of a sudden Gwede Mantashe was talking about the just transition. The phrase that had become synonymous with renewable energy, a cypher for the shift away from coal, had not been mentioned once in hisparliamentary budget speech of 10 July 2019 — and yet now it was something that had to be “managed”.

In the same address, Mantashe warned against positioning renewables as “the enemy of other technologies,” arguing that South Africa needed to “move away from pollution” and “take into account climate change”.

For the record, this was the same man who, in April 2019, when officiating at the opening of Sasol’s R5.6-billion Impumelelo Colliery in Mpumalanga, had urged the coal industry to push back against the perception that its product was unclean — the industry was “under siege” and needed to work on its image, he’d suggested, ignoring the fact that Impumelelo was about to pump a volume of C02 into the skies equivalent to the annual fumes from 1.4-million motorcars.

As it turned out, on the same day that the Presidency was publicising Ramaphosa’s UN statement, Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Minister Barbara Creecy was remarkably “on message” — she was in a meeting with her German counterpart, Svenja Schulze, discussing how the German government had collaborated with trade unions on its own just transition. And at the climate summit itself, International Relations Minister Naledi Pandor was promising that South Africa would not invest further in coal.

Taken by themselves, these coincidences proved nothing — they were at best an indication that something was afoot. But taken together with the global headwinds, the evidence was stacking up. Crucially, there was also Ramaphosa’s reference, near the top of his UN statement, to the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

At the UN climate talks in Bonn in June 2019, as Daily Maverick reported, the South African delegation had been in possession of a “secret” and “confidential” document that instructed them to refrain from committing to the landmark report. Now, Ramaphosa was admitting that the report had “identified southern Africa as a climate change hot spot,” a region that was “likely to become drier and drastically warmer even under 1.5 or 2 °C of global warming.”

If this sudden acknowledgement of the scientific consensus was nothing more than an expedient economic choice, did it really matter? By some accounts, the business-as-usual alternative to the proposal out of the presidential task team would send South Africa into a situation a whole lot worse than a debt trap. As Michael Sachs, former head of the budget office in the Treasury, told the Financial Mail in August, it was arguably “less painful” to go to the Government Employees Pension Fund (with its R1.8-trillion in assets) for an Eskom bailout than to the International Money Fund.

If that were to happen, not only would the South African taxpayer be subsidising coal-fired power at rates that make today’s look cheap, but the vested interests would bloat to incurable proportions while ordinary citizens choked to death on the poisonous air and climate collapse ravaged the food and water supply.

Or? Or South Africa could turn on the lights and show the world how to redeem an energy sector.

2 October 2019

DAILY MAVERICK