The hidden climate costs of America’s free parking spaces

Street parking takes up space and incentivizes driving. New curb management companies are trying to help cities better use this space

The street space occupied by parked cars may not seem like much, but it adds up. The US has an estimated 3.4 spaces for every car. In New York City, the amount of road space reserved for parking is roughly the size of 12 Central Parks, according to one estimate, and most of the city’s 4m street parking spots are free.

“The curb lane is some of the most valuable land on Earth,” said Donald Shoup, a transportation professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “I think that’s our biggest mistake, to take some of the most valuable land on Earth and give it away, free, to cars.”

Street parking doesn’t just take away space. It can inform how people get around. “Parking is one of the things that has a really powerful impact on people’s decisions whether to drive or not,” said Daniel Firth, transportation director at C40 Cities, a network of more than 100 cities around the world with ambitious climate goals.

Shoup and others have found that underpriced street parking keeps people driving in cities, even in those that have good alternative transport options. More people driving means more city traffic – increasing congestion and pumping out pollution.

But cities that want to price, or even convert, free street parking face obstacles – and not just from drivers. Most cities don’t have enough information about how their curbs are used, making it difficult to decide how to manage this valuable space.

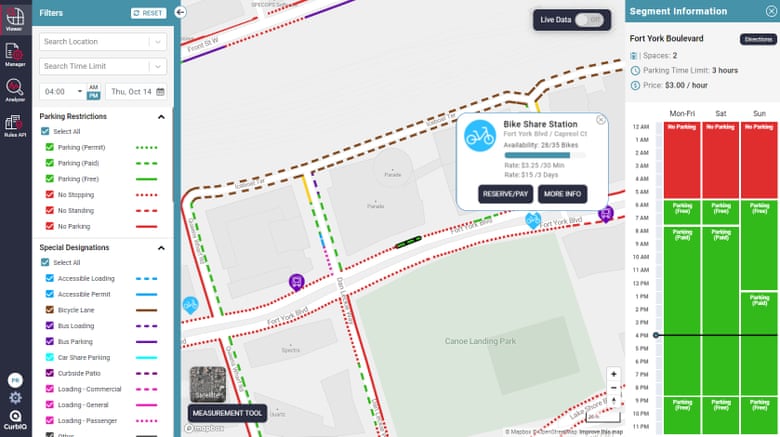

Companies offering curb management technology have sprung up to try to fill this gap, with promises to help cities reclaim their curbs. Their digital platforms map parking spaces and curb use around cities.

Having the information in one place and being able to visualize curb spaces on a map is vital, said Peter Richards, who leads the development of software product CurbIQ at Canadian consulting company IBI Group. CurbIQ was born out of years of working on parking strategy projects for cities and realizing cities don’t have easily-accessible, digitized information about their curbs, Richards said.

The endgame is to help cities reduce car numbers – along with congestion, noise, and pollution – while making better use of spaces and still meeting people’s mobility needs.

The prospect of snagging a free or cheap street parking spot compared with an expensive off-street spot keeps drivers cruising, said Shoup, who has led surveys of drivers stopped at city traffic lights to ask them why they are driving. In one instance, 68% of the drivers surveyed in a Los Angeles neighborhood were cruising for a parking spot.

The availability of free street parking can also inflate car ownership. A study of the four biggest cities in the Netherlands, found that higher parking costs in city centres accounted for about 30% of the lower car ownership rates compared with the outskirts. “You can reduce car ownership quite significantly by making parking more expensive or by reducing the amount of parking you build,” said Jacob Baskin, the co-founder of Coord, an NYC-based curb management company.

And there is data to show city residents may prefer less parking. A survey of London residents found that their top choice for using curb space was to plant trees, Shoup said. Parking ranked fifth.

One of the first steps that CurbIQ and Coord do for cities is to lay out digitized information about the existing permitted uses of curbs on a map – usually by driving around and using machine vision software to capture the street signs – forming the foundation of a city’s curb management platform. “It’s a lot easier to make decisions and plan when you have all this information together,” said Richards.

During Covid, the political barriers to reclaiming curb spaces from free street parking were removed, said Maya Ben Dror, who leads transportation at the World Economic Forum. Commuters started working from home, freeing up parking spaces. Meanwhile, restaurants and other businesses needed outdoor space in cities. That allowed curb management companies to really grow during the pandemic, she said.

Cities used Coord’s platform, said Baskin, to figure out “here’s where we have space where we think we can repurpose, to either be restaurant seating or pickup and drop-off space, in ways that will benefit the city”.

During the summer of 2021, IBI staff used CurbIQ’s software to help the City of Toronto launch its CafeTO program that allowed restaurants to set up patios on appropriate curb space – identifying those far enough away from fire hydrants, traffic intersections or transit stops. Having a map of curb spaces and their regulations helped the city move quickly, said Richards.

Coord is working with cities such as Aspen, Colorado, to designate smart zones – curb spaces reserved for gig and delivery drivers to book through an app when they are approaching their destinations. Home deliveries and ride-shares continue to rise in popularity and drivers need temporary curb space to complete pick ups and drop offs safely. When free street parking dominates, drivers either have to circle around the neighborhood looking for parking or simply double park, holding up traffic, increasing pollution, and endangering pedestrians and bicyclists.

“Double parking can really snag up traffic,” said Baskin. “People hate it.” Smart zones could help cities manage the competition for curb space among these drivers and ease congestion from their cruising, said Ben Dror. Both Coord and CurbIQ are working to quantify the tangible benefits, such as reduced emissions.

Many businesses will reflexively object to the conversion of free parking spaces in front of their shops, fearing a loss of customers. But often, business owners overestimate how much their customers are arriving by car, said Firth. A study in Seattle found that sales revenue increased 5.4% among downtown restaurants after paid parking hours were extended, Richards said, because more customers were coming and going. “Instinctively, everyone’s like if you got rid of free parking, our business will die. That is wrong,” he said.

Street parking is so ubiquitous that converting it feels like a loss. It is a powerful psychology that makes many resistant to the idea, said Firth. “We value the loss of something much greater than the gain of something else.”

The patios, parklets, and bike lanes that took over street parking spaces during the pandemic has shown the possible uses of a city curb other than to store empty cars. “There’s been this little space where we can demonstrate, first of all, the loss of the parking was maybe not as bad as people thought, and the gain of the patio was way better than people thought it would be,” Firth said.

Converting space could also help cities move more efficiently and more sustainably, said Ben Dror. Cars travelling on a single 10-ft-wide lane move about 1,600 people an hour in cities, whereas converting the same lane to a protected, two-way bike lane, for instance, would allow 7,500 people to get around. A lane delineated for transit, whether for buses or trains, could move 8,000 people an hour, she said. “If we were to use a lane, which is a public space, more efficiently, we would seek to use it for something that is healthier for people and for the air.”

Any efforts that help us shift away from driving and towards shared and active modes of transport such as walking, biking, scooting, or public transit are key to tackling the climate crisis, said Ben Dror. Making systemic changes in the way we get around could help prevent an additional million tons of carbon emissions a year by 2050, on top of those saved by electrifying vehicles, she said. And as the time that we have left to limit climate change effectively dwindles, every ton of greenhouse gas that we don’t emit counts.

5 November 2021