Climate crisis: Arctic sea ice freezing at latest date on record.

Slow formation of ice north of Siberia comes after record-breaking heatwave earlier this year

It is mid-November and the Arctic has already been plunged into 24-hour darkness for the winter, but two months after the normal point at which the sea ice begins to refreeze into the huge sheets which cap the top of our planet, enormous areas of open water remain.

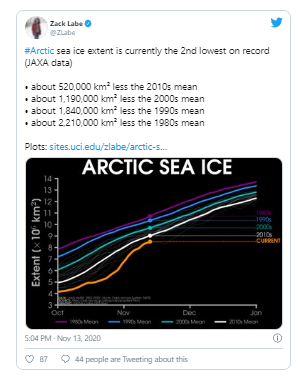

The record-breaking delay comes after the average ice extent for October was the lowest in the satellite record, and means current ice coverage is roughly the same as it was during the height of the summer, when melting after the previous winter was well underway.

The lack of ice means the Arctic sea ice extent is currently the lowest for this time of year, for at least a thousand years, scientists have said, though refreezing has now begun.

Professor Martin Siegert, co-director of the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London told The Independent: “This year is an unusual year. The lowest recorded sea ice extent in the summer was in 2012, but this year is really unusual for two reasons. The first is that at the start of the summer, the sea ice melted away really quickly. Much more quickly than in 2012, but it didn’t continue. It sort of bottomed out above the 2012 level. But whereas in 2012 it started to freeze back more quickly, in 2020 it has taken its time getting back.”

He added: “For this time of year - in November - it’s the least amount of sea ice we’ve ever seen. Just as in May and June it was the least amount of sea ice we’d ever seen at those times, but not in August and September, so we haven’t broken the 2012 minimum record, but at other times of the year we certainly have.”

The total Arctic sea ice volume for October 2020 was about 58 per cent below the 1979-2019 average, meanwhile the October 2020 global land and ocean surface temperature was the fourth highest in the 141-year record, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa).

The key area of concern is the Laptev Sea, north of Siberia, which is known as a main “nursery” of Arctic sea ice. The sea is a vital area for sea ice formation which then moves up to the north pole.

The ice formed in this area is also a vital resource for a wide array of arctic species, as ice formed in the Laptev sea transports nutrients westward which feed Arctic plankton, which in turn supports the fish and marine mammals further up the food chain.

The sea, which is also known as the “birthplace of ice,” also thawed earlier in 2020 than in any previous year since records began.

As the ice is lost, opening up ever larger tracts of open water to direct sunlight, more and more of the Sun’s energy is absorbed, warming the ocean further, amplifying global heating, and inevitably altering the food webs upon which innumerable species depend to survive.

Dr Isobel Lawrence, a research fellow at the University of Leeds, told The Independent this could have an impact on a global scale.

She said: “Sea ice plays a pivotal role in regulating Earth's climate. There are processes we understand very well, like how the bright surface of sea ice reflects incoming solar radiation back into space. This means that the loss of sea ice drives further warming, a positive climate feedback known as the albedo feedback.

“There are other processes that we understand less well, like sea ice's role in global ocean circulation. This means that losing the sea ice will have longer-term consequences for the global climate that we can't currently predict.”

The delayed refreezing of the sea ice comes after Siberia saw a record-breaking heatwave earlier this year, with the highest temperature ever known inside the Arctic Circle, recorded in June when 38C was recorded in the town of Verkhoyansk.

Meanwhile other parts of the Arctic saw temperatures soar above 30C and unprecedented wildfires set new emissions records. The blazes emitted a record 244 megatonnes of carbon dioxide a rise of 35 per cent from 2019, which was also a record setting year.

Professor Siegert said: “We need much more data, and much more measurement of the ice to understand [the delayed refreezing of the ice], but we can speculate, and those speculations are quite obvious: We’ve had crazy levels of heating in the Siberian Arctic bordering the Laptev Sea, the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea - the relatively shallow Russian arctic waters - and that heat is [absorbed by] the ocean, so it simply takes longer to form that ice from a sea that is relatively warm compared to what it would have been under a normal year.

“But we need a lot more evidence and a lot more data to be certain about this.

“There are other reasons to point towards why sea ice extents might be different, for example, the storminess of the ocean and the seas is another way you can have less ice - it simply breaks it up.”

However, he said though the extremes of 2020 had “caught people by surprise”, the overall patterns had been predicted 50 years ago.

“The warning signs have been around since the 1970s that the sea ice was reducing, so if we wanted an early warning system, we’ve gone past it. This is the next stage. We’re seeing ice start to decay at a faster and faster rate. This is something that was predicted - that by the middle of the 21st century there’d be summer times without any sea ice.

Dr Lawrence added: “Watching sea ice decline along its predicted trajectory is a stark reminder that the climate crisis is not going to go away. Year on year we will continue to lose Arctic sea ice unless we drastically curb greenhouse gas emissions, now.”

20 November 2020

INDEPENDENT