How the climate crisis is affecting wildfires around the world.

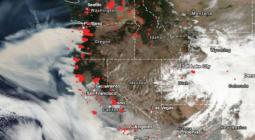

This year has seen wildfires of unprecedented scale, from California and the Amazon rainforest to remote corners of the Arctic.

More than 4 million acres have burned in California alone in 2020, a record for one year. In the US west, dozens of people have been killed, and thousands more are now homeless and displaced.

Intense wildfires have swept across the Arctic Circle, surpassing 2019, amid record carbon emission levels. In Brazil's Amazon fires are at the highest levels in a decade.

-

What causes wildfires?

The overwhelming majority of climate scientists agree: although fires are part of the ecosystem in some regions, the climate crisis is making them more frequent and intense.

Dozens of studies have linked larger wildfires in the US to global heating from the burning of fossil fuels.

2020 has been one of the hottest years on record. Snow melt earlier in the year combined with droughts and higher temperatures lead to drier soil and vegetation which is primed to burn.

In the US, the last National Climate Assessment, produced by the federal government, linked “human-caused climate change” with wildfire increases.

Wildfires and climate change form a vicious circle: the carbon pumped into the atmosphere by fires increases global heating, further drying out the land and vegetation, making it more susceptible to catching fire.

In the Arctic this can have particular potency. Fires have largely burned unabated as the region is difficult to access and sparsely populated. The blazes are fuelled by the boreal forest wrapped around the top of the northern hemisphere, peat bogs and tundra, which produce more smoke than trees or grass when they catch fire. Boreal forest, peat bogs and tundra all have higher concentrations of carbon which spew even more CO2 into the atmosphere when burned.

Australia’s devastating fire season in 2019 was largely caused by parched lands from a sustained drought, with 2019 the hottest and driest year ever recorded on the continent, Physics Today reported. However the situation was complex. The wildfires were exacerbated by a very rare occurrence: Stratospheric warming suddenly occurred in the region due to the breakdown of the Antarctic polar vortex.

Wind also acts as a driving force for wildfires. The Santa Ana winds, which power ferocious wildfires in California, are likely to become less humid by 2050, making them more likely to spread blazes, according to Professor Alex Hall from UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

Around 85 per cent of wildland fires in the US are caused by humans, the US National Park Service says, be that intentionally or by accident.

In parts of the Amazon, fires have been set deliberately to convert tropical forest to savanna in order to farm, raise cattle or build homes.

Central Kalimantan on Borneo island declared a state of emergency in July due to wildfires set to clear land for agriculture.

The 2018 Camp Fire blaze in California which killed dozens of people was down to poor maintenance of power lines by Pacific Gas & Electric.

-

What about forest management?

Donald Trump railed against bad forest management last month during a visit to California in the wake of devastating wildfires, while ignoring the impact of the climate crisis.

However the president is partially correct: forest management plays a role but it does not fully explain the devastation, particularly in the US west.

“Raking the leaves on forest floors is really inane. That doesn’t make sense at all,” Ralph Propper, president of the Environmental Council of Sacramento, told the Associated Press. "We’re seeing what was predicted, which is more extremes of weather.”

There is an added problem of invasive grasses. People who settled in California planted non-native grasses which overwhelmed native plants and burn more quickly.

-

How does the ‘wildlife-urban interface’ play a role?

The stakes during wildfire season - which still hasn’t reached its peak - have been far greater in recent years as an increasing number of homes and businesses are built in areas known as the "wildland-urban interface” (WUI).

This is particularly pronounced in California where housing developments are increasing in the WUI.

Developers are pushing further into wildfire-prone areas as population growth clashes with a housing shortage and an affordability issue, exacerbated by the tech boom in northern California.

21 October 2020

INDEPENDENT