Ozone Hole Over Antarctica Is One of the Biggest in 15 Years.

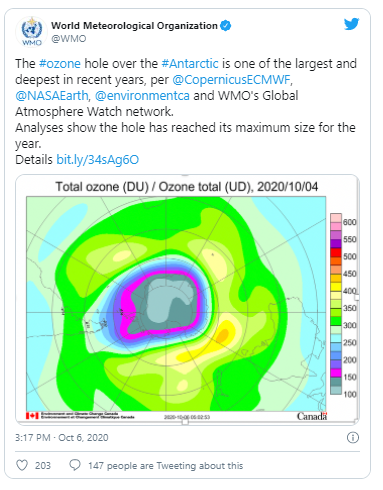

The hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica is one of the largest and deepest in the past 15 years, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said Tuesday.

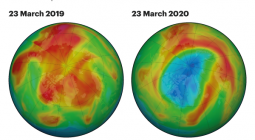

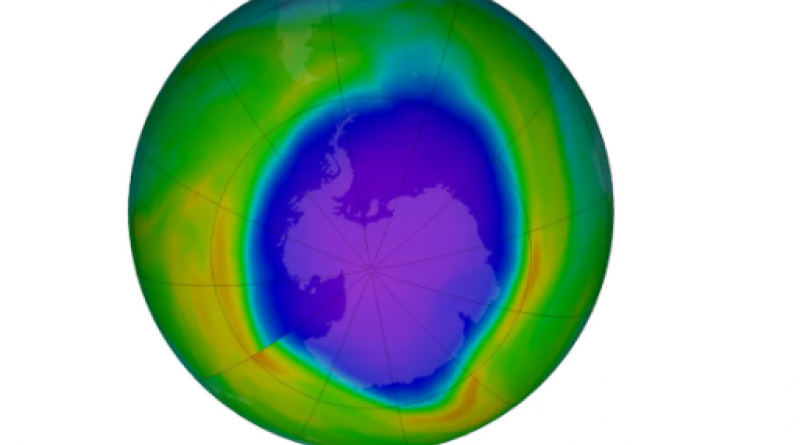

The ozone hole over Antarctica usually starts to grow in August and reaches its peak in October, The Associated Press explained. This year, it peaked at 24 million square kilometers (approximately 9.3 million square miles) and is now at 23 million square kilometers (approximately 8.9 million square miles), the WMO said. This means the hole is larger than the average for the past decade and extends over most of Antarctica.

"With the sunlight returning to the South Pole in the last weeks, we saw continued ozone depletion over the area. After the unusually small and short-lived ozone hole in 2019, which was driven by special meteorological conditions, we are registering a rather large one again this year, which confirms that we need to continue enforcing the Montreal Protocol banning emissions of ozone depleting chemicals," Vincent-Henri Peuch, director of the EU's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) at ECMWF, said in the WMO press release.

The ozone layer is important because it protects the earth from dangerous ultraviolet radiation, CAMS explained. In the late 20th century, that layer was damaged by the human release of ozone-depleting halocarbons, which the Montreal Protocol of 1987 sought to control.

But the size of the ozone hole every year is also impacted by specific weather conditions. This year, a strong polar vortex has chilled the air above Antarctica, and consistently cold air creates the ideal conditions for ozone depletion.

"The air has been below minus 78 degrees Celsius, and this is the temperature which you need to form stratospheric clouds — and this quite (a) complex process," WMO spokesperson Clare Nullis said at a UN briefing reported by The Associated Press. "The ice in these clouds triggers a reaction which then can destroy the ozone zone. So, it's because of that that we are seeing the big ozone hole this year."

Specifically, the ice can turn nonreactive chemicals into reactive ones, the WMO explained. Light from the sun then triggers chemical reactions that deplete the ozone layer.

The Montreal Protocol has been hailed as an example of effective international collaboration on a major environmental problem. Last year's hole over Antarctica was the smallest it has been since the hole was discovered, but this was due to unusual weather, not emissions reductions, ABC News reported.

"There is much variability in how far ozone hole events develop each year," Peuch said in the WMO release.

The 2018 hole was also on the larger side.

Still, the WMO and the UN Environment Programme determined in 2018 that the ozone layer was on the road to recovery and could return to pre-1980 levels over Antarctica by 2060.

8 October 2020

EcoWatch