‘Massive Victory’ for Nuclear as Three Mile Island Plant Set to Reopen

The owner of the shuttered Three Mile Island nuclear power plant said Friday that it plans to restart the reactor under a 20-year agreement that calls for tech giant Microsoft to buy the power to supply its data centres with carbon-free energy.

The announcement by Constellation Energy, the country’s largest nuclear operator, comes five years after its then-parent company Exelon shut down the plant, saying it was losing money and that Pennsylvania lawmakers had refused to subsidize it, The Associated Press reports.

“The symbolism is enormous,” Constellation CEO Joseph Dominguez told the New York Times. “This was the site of the industry’s greatest failure, and now it can be a place of rebirth.”

Heatmap headlines the announcement as a “massive victory for nuclear power,” commenting that the whole U.S. industry will benefit from the deal.

“The days of nuclear power plants shuttering not because of old age, safety concerns, or local opposition, but because of the economics of subsidized wind and solar and cheap natural gas, are likely over,” writes reporter Matthew Zeitlin. “New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Illinois all provided subsidies to their state’s nuclear fleet as plants were threatened with closure. California’s Diablo Canyon plant has seen its decommissioning delayed and received federal aid to help stay open. At a time when states representing a big chunk of U.S. power consumption have aggressive emissions reduction goals and worries about power reliability, money is often easily found to keep nuclear plants open.”

“Now, THIS is additional clean supply,” writes Princeton University energy systems specialist Jesse Jenkins on social media. “Bravo. It is remarkable to see a handful of nuclear reactors shuttered in the last decade due to poor revenues contemplating restart now. Palisades, now TMI. Who is next? Maybe it was unwise to let these plants close in the first place eh?”

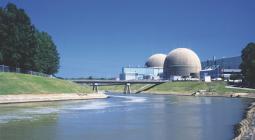

The Times recalls that Three Mile Island “became shorthand for the risks posed by nuclear energy after one of the plant’s two reactors partly melted down in 1979. The other reactor kept operating safely for decades until finally closing, for economic reasons, five years ago.”

But now, “a revival is at hand.”

The news came just days before 14 of the world’s biggest banks and financial institutions promised to boost investment in nuclear energy, the Financial Times reports.

“At an event on Monday in New York with White House climate policy adviser John Podesta, institutions including Bank of America, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Citi, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs will say they support a goal first set out at the COP28 climate negotiations last year to triple the world’s nuclear energy capacity by 2050,” the U.K.-based publication wrote Sunday. “They will not spell out exactly what they would do, but nuclear experts said the public show of support was a long-awaited recognition that the sector had a critical role to play in the transition to low-carbon energy.”

A(nother) Nuclear Renaissance

The plan to restart TMI’s Unit 1 comes amid something of a renaissance for nuclear power, AP writes, as policymakers are increasingly looking to it to bail out a fraying electric power supply, help avoid the worst effects of climate change, and meet rising power demand driven by data centres.

The plant, on an island in the Susquehanna River just outside Harrisburg, was the site of the United States’ worst commercial nuclear power accident, in 1979. The accident destroyed one reactor, Unit 2, and left the plant with one functioning reactor, Unit 1.

Buying the power is designed to help Microsoft meet its commitment to be “carbon negative” by 2030.

Microsoft wouldn’t say which of its data centres will be powered by the nuclear plant, but the mid-Atlantic electricity grid spans from Virginia, a data centre hub for Microsoft and other tech giants, to Ohio, where Microsoft has plans for a new data centre complex outside Columbus.

Constellation said it hopes to bring Unit 1 online in 2028. Restarting the reactor will require approval from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, as well as permits from state and local agencies, Constellation said. Utility Dive says Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro is urging the region’s electricity system operator, PJM Interconnection, to fast-track approval for TMI, on the heels of a report that PJM is blocking a pathway for battery storage that could unlock tens of thousands of megawatts of new grid capacity.

To restart Unit 1, Constellation will spend US$1.6 billion to restore equipment including the turbine, generator, main power transformer, and cooling and control systems. It is not currently seeking state or federal subsidies to help, it said.

Microsoft and Constellation didn’t release terms of their agreement.

Jacopo Buongiorno, a nuclear science and engineering professor and director of MIT’s Center for Advanced Nuclear Energy Systems, said Microsoft will likely pay above market price for electricity that is both carbon-free and reliable.

Restarting the plant is realistic, but not easy, Buongiorno said.

“It all depends on what’s the state of the components, the systems,” Buongiorno said.

The process will go fairly smoothly if they were maintained well while it was shut down, Buongiorno said. A Constellation spokesperson said the plant itself is in excellent condition.

The closest example of restarting a nuclear plant is under way in Michigan, Buongiorno said. There, the U.S. government has promised a $1.5 billion loan to restart the Palisades nuclear plant, shut down in 2022.

AI Drives Up Demand

The business model of the Constellation-Microsoft agreement makes sense for both sides, Buongiorno said, adding that it is cheaper to restart a nuclear power plant than to build one from scratch. Already intact are transmission lines, cooling towers, the control buildings, and concrete containment structures.

Constellation’s announcement comes after a wave of coal-fired and nuclear power plants have shut down in the past decade as competition from cheap natural gas flooded power markets.

That has elicited warnings that the U.S. is facing a grid reliability crisis. Meanwhile, demand is growing fast from data centres run by tech giants like Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google to provide cloud computing and digital services such as artificial intelligence systems.

In the U.S., growth in electricity demand is concentrated in states—primarily Virginia and Texas—that are seeing the rapid development of large-scale data centres, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said.

The data centres’ share of U.S. electricity use in the United States is around 4% currently. Some projections show that doubling by 2030.

The Constellation-Microsoft agreement comes amid a push by the Biden administration, states, and utilities to reconsider using nuclear power to try to limit planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector.

Last year, Georgia Power began producing electricity from the first American nuclear reactor to be built in decades, after the accident at Three Mile Island froze interest in building new ones.

Before it was shut down in 2019, Three Mile Island’s Unit 1 had a generating capacity of 837 megawatts, enough to power more than 800,000 average U.S. homes, Constellation said.

The destroyed Unit 2 is sealed, and its twin cooling towers remain standing. Its core was shipped years ago to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Idaho National Laboratory. What is left inside the containment building remains highly radioactive and encased in concrete.

The late 2022 debut of OpenAI’s ChatGPT—built with help from Microsoft data centres—ignited worldwide demand for chatbots and other generative AI products that typically require large amounts of computing power to train and operate.

Google and Microsoft both acknowledged this year that AI’s electricity needs are making it harder for them to meet the ambitious climate targets they set before the AI boom.

“Microsoft, above and beyond their own products, are also providing the compute for OpenAI, which is growing and expanding very ambitiously,” said Sasha Luccioni, a researcher at AI company Hugging Face who has called attention to AI’s carbon footprint. “They have to scramble to get all the energy they can in order to be able to fuel that growth.”

Cover photo: Constellation Energy/wikimedia commons