What 2024’s Historic Elections Could Mean for the Climate

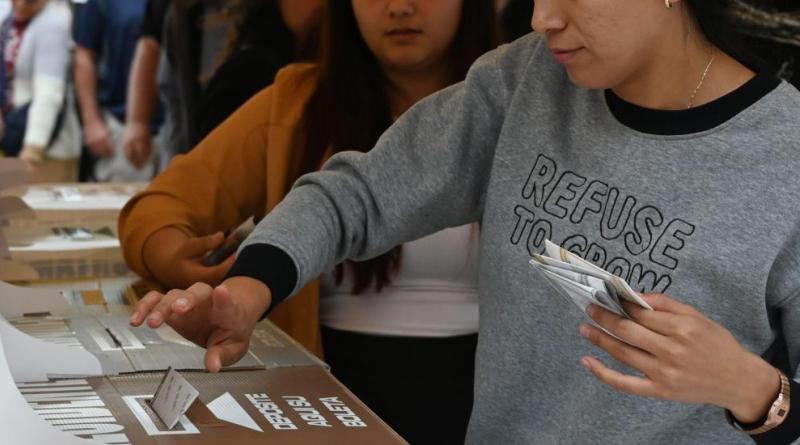

Cover Image by: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo

This is the biggest year in modern history for elections around the globe. Citizens of at least 64 countries — collectively home to about half of the world’s population — have, or will, cast votes for national leaders in 2024. The implications of these elections for the climate and our shared future cannot be overstated.

In late July, the world experienced its hottest day ever recorded, after more than a year of consecutive monthly record-high temperatures. Relentless regional heatwaves, devastating wildfires and dire water shortages abound. The world’s most vulnerable people and communities, most of whom bear the least responsibility for climate change, are feeling its impacts most acutely.

Global leaders will play a critical role in addressing these interconnected crises and ensuring a livable future for everyone. In the latter half of this pivotal decade for climate action, the world needs leaders who will work to rapidly slash greenhouse gas emissions, shift their economies away from fossil fuels, protect and restore their lands, and invest in building communities’ resilience to climate shocks.

With some key races already decided, and as the main issue framing WRI’s 2024 Stories to Watch (the biggest issues of the year impacting people, climate and nature), here’s what WRI country and policy experts are saying about the world’s most consequential elections for climate so far:

Indonesia

Indonesia boasts some of the world’s most abundant natural resources, the management of which is inextricably tied to the archipelagic country’s presidential policies. Following its February election, former army general and current defense minister Prabowo Subianto is set to assume office on October 20. The widely-held expectation is that his administration — which includes the current president’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as vice president-elect — will continue to advance the previous administration’s policies, although whether the new administration will also continue outgoing President Joko Widodo’s climate commitments, remains to be seen.

“Economic development will still be the priority for the next five years, and there are wide opportunities for the country supported by businesses and other non-state actors to strengthen climate resilient, low carbon, and socially inclusive development,” says Arief Wijaya, managing director of WRI Indonesia.

The president-elect has already promised to secure national food sovereignty through the country’s food estate program, which will be expanded to more than 40 million hectares of degraded lands and forests in the country. This strategy will help reduce the pressure solely on Indonesia’s forests and encourage a mosaic landscape approach to restoration.

As the world’s leading exporter of palm oil, Indonesia plans to expand its production as part of a larger focus on biofuels. But to do so, it should encourage a sustainable palm oil certification.

Lastly, as the incoming administration looks toward energy sovereignty, it hopes to expand mining of its vast resources of nickel, a critical mineral for electric vehicle batteries and other clean technologies. To reduce environmental impacts, the incoming administration will need to follow the existing plan created by Indonesia’s Ministry of Planning.

Because Indonesia’s incoming parliament will be a coalition of different political parties, the opposition will relatively lack the ability to challenge any potentially harmful policies. “The hope is to have the role of civil society organizations and non-state actors, including private sectors, to be more prominent for checks and balances of the government policies for the next administration,” Wijaya explains.

India

In India, more than 640 million citizens made their way to the polls amid scorching heat between April and June, marking the largest election the world has ever seen. Though climate change was not always highlighted as an electoral issue in the candidates’ campaigns, major party manifestoes included chapters on climate and addressed concerns about rural livelihoods and water, which are often exacerbated by climate extremes.

On June 4, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party secured a third term in conjunction with other parties, including regional leaders from Bihar and Andhra Pradesh — states that are highly vulnerable to floods and cyclones, respectively. This could mean that the national agenda might possibly see more mainstreaming of regional needs for climate resilience and a “just transition,” that ensures workers and communities aren’t left behind as the country moves toward a low-carbon future.

The country’s recent elections may not have significant climate implications on the international stage and there are likely to be a continuation of the country’s climate commitments aimed at expanding renewable energy to reach net-zero emissions by 2070.

South Africa

Thirty years after South Africa’s first free and fair elections, voters this May sent the country into a coalition-led government called the Government of National Unity (GNU). The African National Congress (ANC), the dominant political party in the country since Nelson Mandela became president in 1994, dropped its share of votes from 58% in 2019 to a little over 40% in 2024.

Increasing levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality, in addition to corruption at all levels of government and persistent electricity shortages and mismanagement, have been among the reasons cited for the drop in confidence in the ANC.

After brokering a deal to create the GNU, which currently encompasses 10 political parties, President Cyril Ramaphosa will serve a second term. Ramaphosa has historically been a strong proponent of climate action and, specifically, a just transition. For example, he advocated for South Africa’s entrance into a Just Energy Transition Partnership in 2021, through which the U.S., EU and other countries have committed billions to support an equitable transition from coal reliance to clean energy in the country.

This climate ambition is expected to continue through Ramaphosa’s second term, including with Ramaphosa signing the long-awaited Climate Change Bill, providing the first legal basis in the country for acting on climate change. However, implementing costly and complex climate solutions could prove more challenging amid South Africa’s social and economic atmosphere.

Mexico

Mexico City made headlines in early 2024 amid speculation that the city’s taps could run dry in mere months. Fortunately, this “Day Zero” didn’t come to pass. But it highlighted Mexico’s wider water crisis: As of May, more than two-thirds of the country was experiencing moderate to severe drought. And water shortages are just one of the many growing threats facing Mexico as climate change intensifies.

But the country’s next administration could be uniquely positioned to address these challenges. President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, who won on June 2 in a surprise landslide, is not only the country’s first female president, but has a PhD in Environmental Engineering with a strong track record of impact. As Mexico City’s mayor, Sheinbaum worked to expand public transit and deploy one of the world’s largest solar plants. As one of the authors of the preeminent international report on climate change, she’s helped raise awareness about the urgency of the issue and drive action on the global stage.

Avelina Ruiz, climate change manager at WRI México, highlighted the appointment of Alicia Bárcena as secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, who has an extensive track record in promoting the sustainable development agenda in Mexico and at the regional level as executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. “Both the cabinet announcements and the work priorities outlined by the president-elect send a positive signal regarding the importance that the climate and environmental agenda will have in the new administration,” Ruiz said.

After taking office on October 1, Sheinbaum will likely continue her efforts to expand mass transit and public mobility, alongside working to bolster food security through sustainable agriculture, conserve biodiversity and improve water management. She also campaigned on boosting renewable energy investment and promoting rapid decarbonization — although the current administration under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, with whom Sheinbaum is closely aligned, has been criticized for backing domestic oil production and continuing the country’s economic reliance on oil production.

The country is expected to resume its role of international leadership by submitting its 2025 national climate commitment that will showcase how Mexico will achieve a just, resilient and low-emission economy.

European Union

Voters across 27 countries in Europe headed to the polls in June to participate in the European Parliament elections, which take place every five years. The center-right European People’s Party held onto its position as the biggest parliamentary group, but it will need to collaborate with the Social-Democratic Party (the second biggest group), the economic-liberal Renew party and left-wing Green group to achieve a centrist majority. The right-wing protest vote, for which immigration is a central issue, made notable gains, forming a new parliamentary group — called Patriots for Europe — that now constitutes the third largest group in the European Parliament.

Ursula von der Leyen won a second mandate as European Commission president and, together with European Council President António Costa and Kaja Kallas leading foreign affairs, will chart the block’s next course on climate and sustainable development.

“These three will have to make sure that they address some of the main concerns that the European voters have voiced, which center around the cost of living, defense and competitiveness,” says Stientje van Veldhoven, vice president and regional director for WRI Europe.

Van Veldhoven also notes that, concerningly, climate did not rank among those top three issue areas. Although, she says, while it's less visible, Green Deal proposals do fall under the banner of “industrial competitiveness.” These include a continued focus on energy transition, electricity grids and minerals.

The EU must also shift its agricultural policies to help protect landscapes and adapt food production to a changing climate, but this stands to be contentious, as farmers throughout Europe have taken to the streets in recent years to protest environmental legislation. Efforts on nature restoration could face similar challenges.

The EU’s goal of reducing carbon emissions by 90% from 1990 levels by 2040 remains a priority for the Commission, but van Veldhoven says she expects the Commission will have to navigate a challenging political situation in several individual countries.

United Kingdom

In a landslide early-July victory, the United Kingdom’s Labour Party, led by Prime Minister Keir Starmer, won the country’s general election, marking the first shift in party rule since 2010. The change has brought with it a significant majority in the UK Parliament that supports climate action. “I think there's a real sense of excitement that the new government will be a strong force on climate, development and nature, both in terms of domestic implementation and also on the global stage,” says Edward Davey, head of WRI Europe’s UK office. He adds, however, that the country first needs to make meaningful progress at home in order to successfully resume a leadership position at the international level.

hat’s now a real possibility, given the range of climate policy priorities the Labour Party outlined in its manifesto and which it has already begun to deliver. Among them, the UK aims to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, a goal that will require planning system reform and a renewed focus on the just transition.

Other significant climate priorities include a new 8.3 billion pound ($10.6 billion) institution to invest in leading energy technologies and support local energy production; the creation of a new national energy system operator; decisions about the future of nuclear power, carbon capture and storage and hydrogen; and new commitments on fresh water, sustainable land use, and biodiversity protection. In its first days in power, Labour already showed its commitment to advancing climate action by ending the previous administration’s block on onshore wind development.

Davey concludes that we will likely see action that centers on “making fast progress on net-zero implementation at home, coupled with a renewed focus on diplomacy and partnership with other countries. How strong that international leadership proves to be will also depend on whether the UK joins and drives high ambition climate alliances, as well as the pace and nature of its return to the UN’s goal for developed countries to spend 0.7% of their gross national income on international climate, nature and development finance.

France

After a second round of voting in France’s Parliamentary elections in early July, no one group won an absolute majority. A loose coalition of left-wing and environmental parties, the New Popular Front (NFP), won the largest number of seats in the National Assembly by a slim margin. President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist party and the far-right party led by Marine Le Pen came in close behind.

Climate change was not at the forefront of these elections, overshadowed by issues like retirement and immigration policy. The country’s main green party saw its share of votes fall from 13% to just 5%, while it’s far-right party — which has opposed phasing down fossil fuels and other climate actions — saw its share rise to more than 30%.

NFP, which won the largest share of Parliamentary seats, specifically references the threat of climate change in its manifesto. It also promotes increasing renewable energy and expanding domestic production of clean technologies, among other climate-related priorities. Macron, who was first elected in 2017, has yet to appoint a new prime minister whose task will be to deal with the fragmented parliament (an unusual situation for France but common in other European Countries). At the moment of writing, the future figurehead of France’s political leadership, and the country’s trajectory on climate action, remain uncertain.

Looking Ahead

With a few more months left in the year, many elections that will impact how the world responds to climate change are still to take place — including in the United States, the world’s second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions and a central player in driving levels of climate finance.

To chart a more resilient future around the globe, it will be imperative for leaders and governments elected in 2024 to work together to raise their collective ambition — and climate finance to support that — at international settings like the UN’s 29th annual climate conference (COP29) in November. And they must work to rapidly accelerate action on the ground, starting by submitting stronger national climate commitments when they come due in early 2025.

The decisions and actions leaders take today — and public pressure and support for these — will impact the planet’s trajectory for generations to come.