In 2015, the world had 1,496 GW of new coal in development — enough to almost double global coal capacity. Such a large increase in coal power would have been catastrophic for the climate, as coal is the most polluting fossil fuel.However, since then the amount of coal power in development has fallen dramatically to 578 GW. Of all the new coal plants that were in development in 2015, 56% were cancelled or suspended as of 2023, according to our analysis of data from Global Energy Monitor. Only 31% went into operation. The rest are still in development today, alongside additional coal capacity that has been put into development since 2015. It’s clear that growth in coal power is slowing down, meaning the worst-case scenario has not come to pass. But slower growth is not enough. Total coal power consumption was at record highs in 2023. The world needs to reverse course and completely phase out unabated coal power by 2040. That means coal plants in development need to be cancelled and existing coal plants need to be retired.

Lessons From the Coal Boom That Didn’t Happen

Cover Image by: David Lyons/Alamy Stock Photo

In 2015 when the Paris Agreement was reached, its new goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) was at risk of being dead on arrival because the world was on the verge of a coal-plant-building boom.

At the same time, countries need the right policies and finance in place to quickly scale up enough clean power to fill the gap and meet people's energy needs. This has to be an all-in global effort, with the international community providing finance and technological support to developing countries that are dependent on coal.

Here, we explore the history of coal plants cancellations to help understand how the world can speed up cancellation of the remaining coal project pipeline. (We cover retirement of existing coal plants in a separate piece.)

What's Driving Coal Plant Cancellations?

Global electricity needs have continued to grow, so why were so many coal projects cancelled over the last decade?

A big part of the answer is that clean energy filled the gap. The world added 2,032 GW of solar, wind and other clean power capacity from 2015 to 2023, far outpacing forecasts from 2015. Falling costs and improving technology made wind and solar a cheaper and better option, steadily tilting the playing field away from coal. In 2023, coal made up only 9% of new electricity capacity additions, while clean energy made up 83%.

On top of that, coal has lost ground as countries ramp up their efforts to tackle the climate crisis and air pollution. Most of the biggest emitters, such as the United States, European Union and China, have announced goals to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century. These targets are not compatible with the 37-year lifetime of the average coal plant.

The biggest public financiers of overseas coal projects have also committed to stop lending, making it more difficult to finance new coal plants. On the other side, climate finance for renewable energy and other low-carbon solutions has grown.

Finally, not every coal plant in the project pipeline is a firm commitment. Governments and companies may announce plans for new plants before they've secured the necessary financing, developers or support, which means only a subset of projects that are announced are destined to be built. Still, the fact that the number of plants in the project pipeline is shrinking overall is a positive development.

How Do Coal Development Patterns Differ by Region?

When it comes to coal power, Asia is the key region to watch. In 2015, more than 90% of all coal in development was concentrated there, and the pattern has continued since then. China alone has been responsible for more than half of the coal project pipeline. Electricity demand has been rising quickly in many Asian countries, and is expected to continue to grow, improving the quality of life for billions of people. But if this growth comes from coal rather than other sources, it will seriously damage the climate and local air quality.

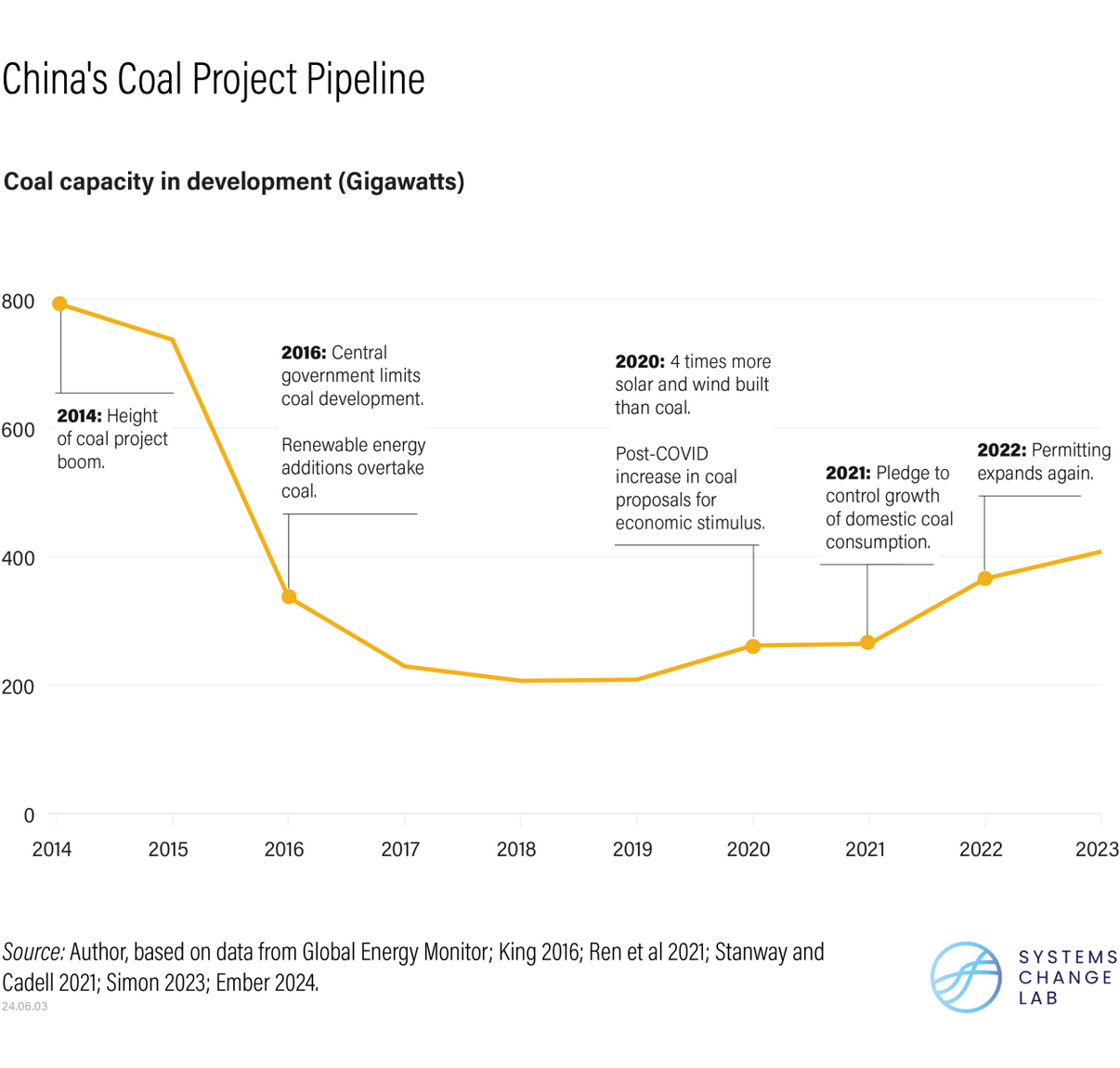

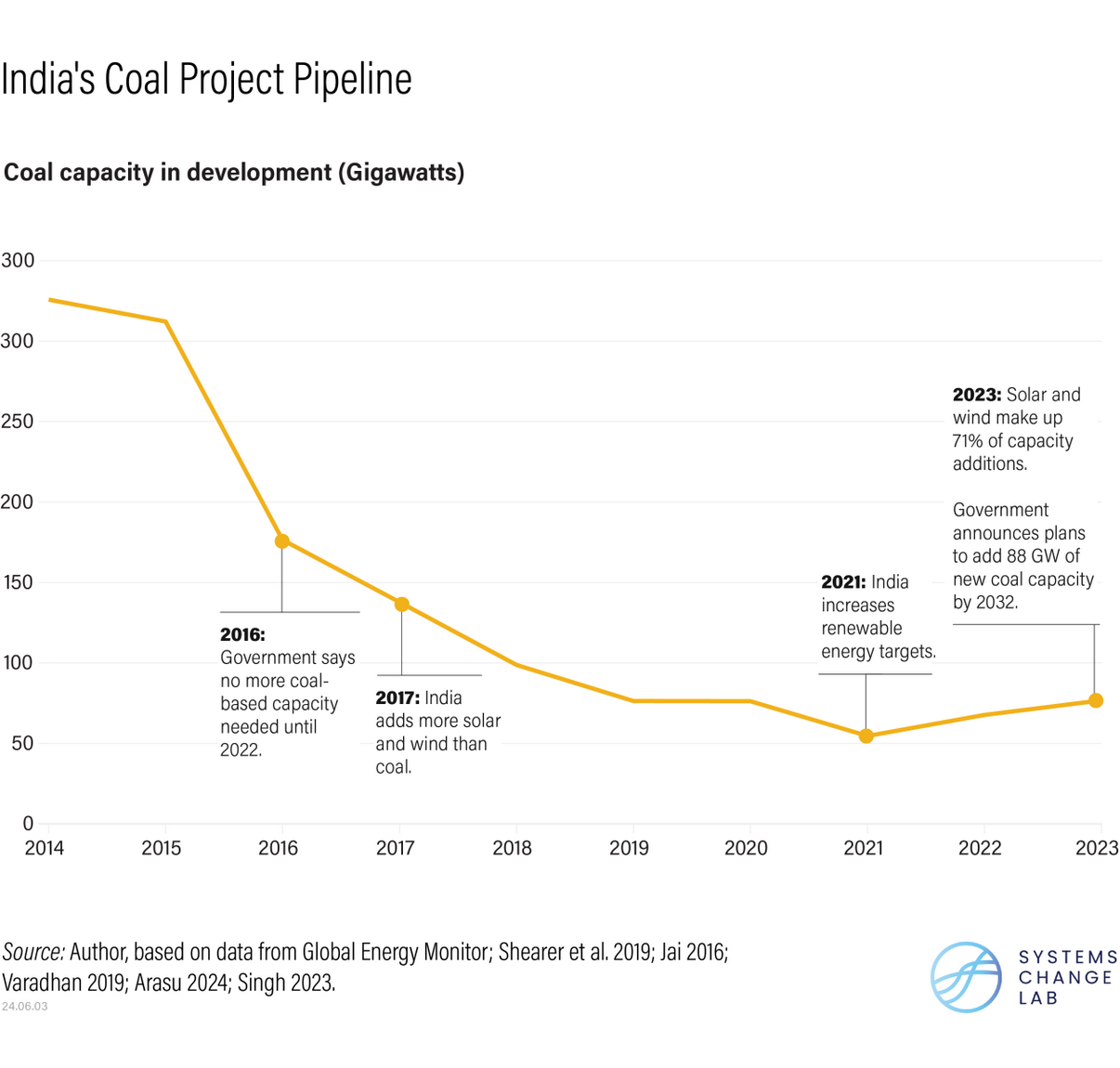

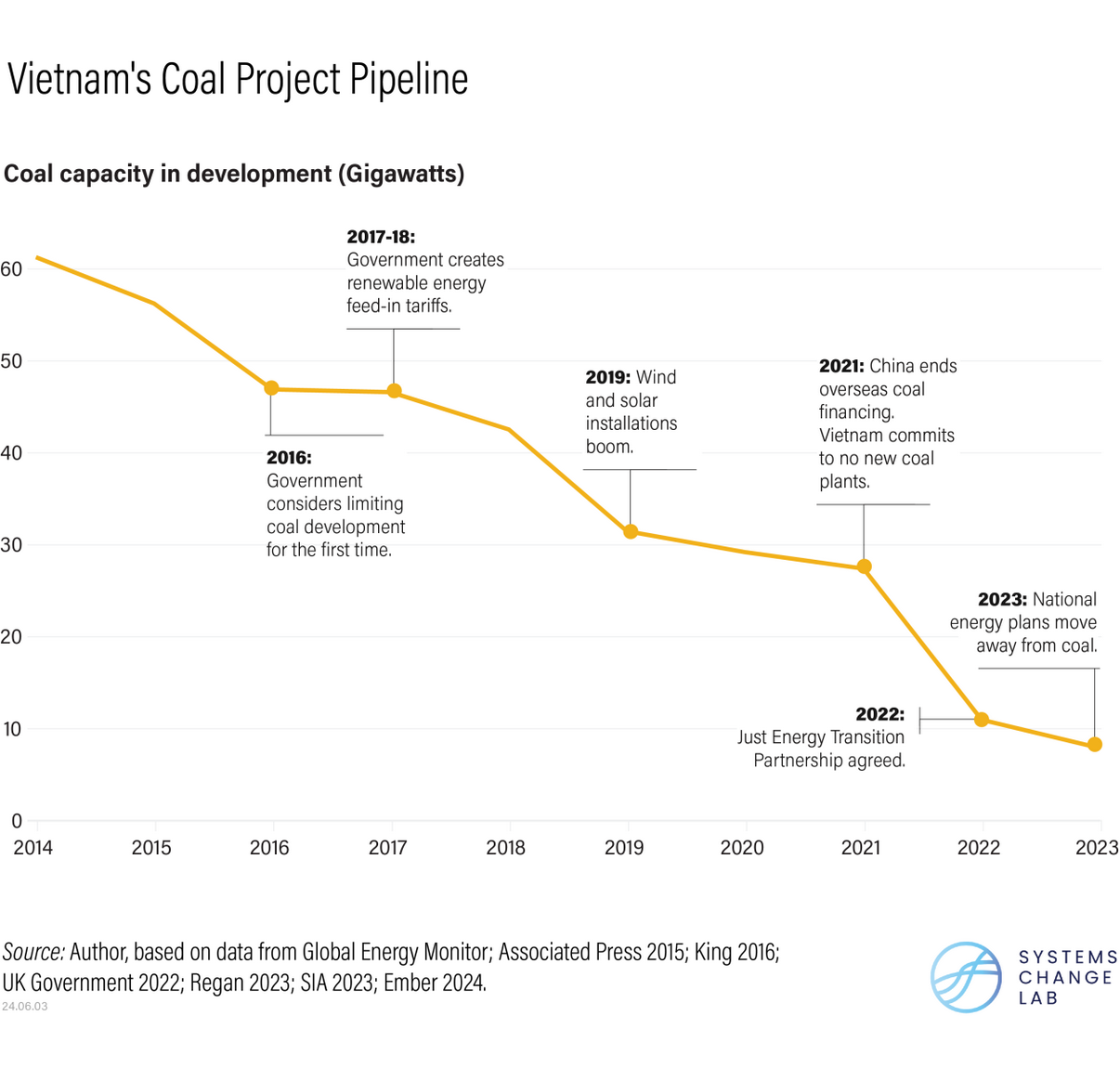

The good news is that the top coal-developing countries in Asia all decreased their coal project pipelines from 2015 to 2023. China's pipeline of coal projects in development shrank from 738 GW to 408 GW. India's coal pipeline plummeted from 312 GW to 77 GW. Turkey and Vietnam stand out among smaller countries, as both had plans to increase their coal capacity multi-fold but ended up cancelling or suspending most of those plans.

Overall, the situation today is better than in 2015, though the amount of new coal still in development in the region would be too much to achieve the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.

Outside of Asia, the amount of new coal developed from 2015-2023 was low. No countries in Europe or the Americas increased their coal capacity by more than one gigawatt over that time period, and many are retiring coal plants. Notably, nine African countries had plans in 2015 to build their first ever coal plants, but none of these had been built by the end of 2023. In a telling example, Egypt had proposed building the second-biggest coal plant in the world, but the government shelved it in 2020, recognizing the need to shift to renewable energy instead.

3 Countries to Watch for Coal Development

To learn what's driving coal cancellation trends — as well as the remaining challenges — let's examine three of the countries that had a lot of coal power in development but managed to substantially shrink their project pipelines.

China restricted coal development drastically, but now it's rebounding.

As the largest coal user globally, the history and future of coal development in China has vast implications for whether the world can meet its climate goals.

In 2015, China had more coal power in development than any other country. The central government had recently shifted more control of coal plant permitting to the provinces, which took this as an opportunity to announce more coal plants that would boost GDP — even if they weren't needed and would lead to overcapacity. Provincial authorities were 3 times more likely to approve permits for new coal plants than the central government had been.

As the environmental, social and economic costs of coal became clearer — for example, with Beijing's record levels of smog — China's government committed to address coal overcapacity and promote a shift to renewables. It issued new restrictions to discourage provinces from proposing or permitting new plants, and the cancellations and suspensions that followed cut the number of coal plants in the pipeline by more than half.

Coal development stayed low for several years even as China's energy demand continued to rise, thanks to the growth of renewable energy. By 2020, China was building 4 times more solar and wind capacity than coal, due in part to strategic government investments. China also became the world's largest exporter of green technologies like solar panels. Yet, permitting and coal financing ticked back up during Covid-19 as a form of economic stimulus.

In 2021, President Xi Jinping announced that China would strictly control the growth of coal use until 2025 and then start to gradually reduce it. Many provinces seemed to interpret President Xi's pledge to mean that pre-2025 was their last chance to build new coal capacity, so the coal pipeline started growing again. But China does appear to be on track to peak coal generation before 2025.

China has also faced challenges with energy security. In 2021, global fossil fuel prices spiked following Covid recovery and Russia's invasion of Ukraine. China had plenty of coal power plants, but not enough coal to run them, which led to power rationing and blackouts in many Chinese provinces. Then in 2022 and 2023, China experienced historic heat waves, provoked by climate change, that increased electricity needs for air conditioning and reduced the supply of hydro power. To compensate, the government fast-tracked more coal projects. In the long term, however, energy security and a stable climate will only be enabled by scaling up clean energy and decarbonizing the energy system.

China's electricity demand will keep growing as the country continues to develop and as it undergoes rapid electrification. Ultimately, new coal will not stop being built until clean energy and energy efficiency can fulfil and exceed all the demand growth.

India's coal project pipeline has plummeted, but challenges remain.

India, the world's second largest coal user, has also made substantial progress in diversifying from coal in recent years. But it faces important challenges in canceling its remaining pipeline.

India experienced a coal permitting boom in the mid-2000s as it moved toward privatization of its coal industry. By 2015 its boom had already started to bust, with investors pulling out of projects that didn't make financial sense. But even then, India still had 312 GW of coal plants in development — enough to more than double the country's coal fleet.

In 2016 India's Ministry of Power said that no new capacity additions were needed at the time, so developers drastically cut back: The coal pipeline fell by two-thirds from 2015 to 2018. It has stayed relatively low since then.

Meanwhile, India has become a clean energy leader. The government has increased the ambition of its renewable energy targets multiple times. India's support for effective auctions for solar and wind helped the technologies lock in lower prices for power distributors, increasing cost advantages over coal. In 2023 clean energy made up 70% of India's new capacity additions.

However, the total amount of energy being built from all sources each year has been lower than in the past. From 2014 to 2016 India added approximately 30 GW per year of all new power capacity, but since then it has only added about 17 GW per year. Coal capacity additions fell so drastically after 2016 that even the substantial growth in renewable energy wasn't enough to keep total capacity additions at the same level. One challenge is that the cost of raising capital for clean energy projects in developing countries like India is much higher than in developed countries, due to higher investment risks.

Much more electricity capacity will be needed as the country develops; today, the average person in India uses 10 times less power than the average person in the United States. The government's stated goals will require adding more than 40 GW of clean power every year until 2030. But with demand for new power rising faster than renewable capacity, the Indian government has said that it intends to build out approximately 88 GW of new coal capacity by 2032.

High-income countries should lend financial assistance and support technology transfers to help India's renewable energy industry grow, so that electricity demand growth can come from clean energy rather than coal. India has to balance multiple different priorities: meeting rising power demand, ensuring it is affordable, keeping the grid balanced, developing domestic industry and reducing emissions. What's more, it will need to watch out for the welfare of the 1.6 million workers in coal production.

Shifting to more clean energy will be challenging, but there are myriad benefits. In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it would help reduce the impacts of air pollution, which causes more than 2 million premature deaths in India each year.

In Vietnam, coal was expected to be the future, but plans are changing.

In 2015, Vietnam had enough coal plants in development to raise coal capacity from 13 GW to 69 GW — a fivefold increase. Like China and India, Vietnam's electricity demand had been growing rapidly as the economy developed, and coal was seen as the best way to meet that need. But while Vietnam did approximately double coal capacity to 27 GW by 2023, most of the rest of the plants in development were replaced by renewable energy.

In 2016, Vietnam's government for the first time announced that it would consider limiting coal development (although this was not reflected in official development plans). In 2017 and 2018, the government introduced strong feed-in tariffs for solar and wind. These incentivized companies to invest in renewables by guaranteeing that the electricity would be bought at a high subsidized rate.

By 2019, Vietnam leapt from installing less than 0.2GW of wind and solar per year to more than 5GW. Whereas renewable energy received a government guarantee and could be built quickly, coal plants faced long development times, public opposition and difficulty finding financing.

In early 2021, China pledged to end its overseas coal financing. China was the biggest public financer of coal plants in Vietnam. With countries like Japan and South Korea making similar commitments, Vietnam's options for international coal financing started to dry up.

The same year, Vietnam committed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and signed a UN statement pledging to stop building new unabated coal plants. This was a big deal: Of the 39 countries that had any coal in development at the time, Vietnam was one of only four that fully endorsed the statement. With this decisive shift away from coal, Vietnam hoped to attract more international investment in clean energy. It also agreed on a Just Energy Transition Partnership in 2022, in which G7 countries pledged $15.5 billion of public and private capital to support its energy transition. This stipulated that Vietnam would reduce its plans for coal capacity growth and peak emissions by 2030.

The success of the partnership remains to be seen, and some coal plants continue to move into construction. But overall, there has been a major shift in policy: Vietnam's Power Development Plan, published in 2023, reduced plans for coal growth in line with its international commitments and agreements.

While the rapid construction of solar and wind farms in Vietnam has enabled the country's pivot away from coal, it has also created challenges. Power lines are not being built at the same pace, so many renewable sources have been asked to curtail their output. In 2021, when the initial feed-in tariff expired, massive wind power projects were stuck waiting to get connected to the grid as developers negotiated with the government on new rates. The state-owned utility was not expecting to have to pay so much to renewable energy producers, which has strained government finances.

For Vietnam to build out enough renewable energy to meet demand growth, it will need to invest in grid upgrades; build out battery storage; and ensure that renewable energy incentive policies are clear, consistent and sustainable.

Renewables Are the Key to Canceling Coal for Good

It's encouraging that unchecked expansion of coal has been avoided. Thanks in part to cancelled coal plants, the world's emissions trajectory is less dire than what it was in 2015. When the Paris Agreement was reached, the world was on track for global warming of 3.6-3.9 degrees C (6.5-7 degrees F) by 2100; now that projection is more like 2.7 degrees C (4.9 degrees F).

However, this amount of warming would still come with dire impacts for people, ecosystems and the economy — from extreme heat to worsening storms, floods, droughts and more. The ultimate goal is to hold warming to 1.5 degrees C and limit future damage from climate change as much as possible, which the world remains far off track from achieving. If all the coal plants remaining in development are built, it will blow the global carbon budget or else the plants will become stranded assets. On a pathway to net-zero emissions by 2050, more than a trillion dollars in coal power assets could be stranded.

As demonstrated by countries like China, India and Vietnam, the story of coal can never be told without talking about renewable energy. Electricity demand will continue to grow in all the countries that still have coal projects in the pipeline. The rise in demand will need to be met with a rise in zero-carbon electricity sources and increased energy efficiency in order to displace coal and ensure a safer, more livable future for all people.