‘There’s angry people out there’: inside the renewable energy resistance in regional Australia

Photograph: Krystle Wright/The Guardian

In a packed community hall in regional Queensland, a calamitous story is being told. Australia’s east coast is bulldozed into the ground. Rural towns are wiped off the map. Supermarket beef mince hits $60 a kilogram.

The orator is one of the loudest campaigners against Australia’s renewable energy rollout, Katy McCallum.

“Where do you think we are going to be in another 10 years if there’s no farms left, what are we going to eat?” McCallum tells the gathering at Kilcoy, a small town 85km north-west of Brisbane. “We’re going to be starving,” replies someone from the crowd.

The script is well rehearsed. In the last 12 months, McCallum and Jim Willmott, the chair of Property Rights Australia, have delivered the rousing PowerPoint presentation to about 40 community groups in this patch of regional Queensland. She has spoken at anti-renewable rallies in Brisbane, Sydney and out the front of Parliament House in Canberra. This is my third time hearing the spiel.

The pair were invited to speak at an event organised by the Kilcoy group, a handful of neighbours who oppose a proposed large-scale battery storage facility on a property outside town. According to McCallum, who is also the vice-chair of the National Rational Energy Network (Nren), it is one of 125 scattered across the country that formed in opposition to a local renewable energy project.

They are not formally connected. But through social media and presentations like McCallum’s, the same messages ripple through.

It started with transmission lines

About 100km north of Kilcoy, lush cattle pastures line the Wide Bay Highway. Then comes the solar farm: sheets of dark glass rolling over undulating pastures, power lines bowing overhead. Nailed to an odd gum tree by the road’s shoulder are the signs of protest: Powerlink, our gates are locked.

It’s in this battleground that McCallum, an ex-Queensland police officer, had her political awakening. In late 2022 locals came into her general store in Kilkivan and told her that Powerlink, Queensland’s state-owned transmission company, was proposing to build 500KW transmission lines through properties outside town to connect the proposed Borumba pumped hydro project to the grid.

Borumba is considered one of the most significant projects in Queensland’s energy transition. The construction of the transmission lines would involve clearing native vegetation. McCallum considers herself a conservationist, but like most leaders in the anti-renewable campaign, she does not believe in human-induced global heating.

The campaign is framed around environmental concerns but, speaking to locals, their main concern is loss of amenity. Kilkivan, like many hotbeds of anti-renewable sentiment, is a mix of farmland plus hobby and lifestyle blocks. “You spend all your life working in cities, doing the hard yards and then you get to come up here to retire, and they are putting that in our back yards?” says the retired truck driver Matt Cosgriff. “It’s disappointing.”

The proposed route would see the transmission lines erected about 500 metres from Gillian Stephens’ home on her cattle property. Stephens says it has added an “unimaginable stress” to her and her husband’s life. “It’ll absolutely destroy the beauty of the place,” she says.

A local real estate agent, Stuart Hill, says there are mixed feelings on properties within the proposed corridor. In Queensland, landowners receive an average of $300,000 per kilometre of transmission lines that crosses their property.

“Some are outright against it, others are of the opinion that if we can’t stop it, let the money roll in,” he says.

‘I’m stuck here’

About 70km away from Kilkivan, in the town of Kingaroy, the pensioner Karen Mansbridge is crying in her living room. “I want to get out,” she says. “But I can’t, I’m stuck here, it’s keeping me here.”

For eight months Mansbridge has been trying to sell her house to move closer to her children.

Rural lifestyle blocks like hers are in high demand and should sell within 30 days. “But once people realise it’s next to a solar farm they aren’t interested,” her real estate agent says.

The project was opposed by the local South Burnett regional council, but eventually approved through the land and environment court. Mansbridge and her neighbours have not received meaningful compensation: when construction noise was bad she received a $110 voucher for a meal at the local RSL.

“They took one look at us and thought, they don’t have the money,” a neighbour, who did not wish to be named, told Guardian Australia. “The arrogance of that.”

It’s a genuine grievance, which has been plugged into a broader campaign filled with misinformation and disinformation.

Last week the One Nation senator Malcolm Roberts and candidate for Nanango, Adam Maslen, who also attended the Kilcoy meeting, visited Mansbridge’s property and encouraged her to speak at a One Nation event.

One Nation has already recruited McCallum, who has been preselected as its candidate for Gympie. This was not disclosed at the Kilcoy meeting.

Community meetings, just like the online debate, are falling along partisan lines.

‘Noisy minority’

Distant storm clouds obscure the view of the Coopers Gap windfarm from the second storey of Kevin White’s Kingaroy home. It is one of two windfarms west of town, with more proposed.

White says online discourse about the proposed developments has been “vicious”.

“I worry that the noisy minority is having a larger than warranted impact on local council decision-making,” he says.

Community Facebook groups have become “melting pots” of misinformation and disinformation, says the director of Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre, Prof Daniel Angus. Genuine concerns and questions are lumped in with conspiracy theories.

“If you don’t have quality news and information you leave space there for the taking for anyone who can fill it with whatever crap they like,” he says.

Facebook is a key recruiting ground for Nren. Willmott’s community presentation includes a survey conducted by Nren and Property Rights Australia that was distributed through anti-renewable groups on the social media platform, and is an effective census on its members: just 13% of respondents were 44 years old or under and the most common occupation selected was retired.

Further down the Wide Bay Highway is Jo Schembri and Jim Mewburn’s cattle property. Last year they accepted an offer from Ag Energy Australia to build a battery energy storage system on the property.

They now work part-time for that developer to engage with farmers interested in hosting a renewable energy project on their own land, and have spoken to more than 20 farmers from New South Wales and Queensland. The right development can be “life-changing” for farmers, Mewburn says, providing economic stability on otherwise marginal country – made more marginal by an increasingly unpredictable climate.

“We’ve forgotten why we are doing this in the first place,” he says. “We need to take action as soon as possible to start to minimise the effect we’re having on the planet.”

Stuart Nicholson lives at an off-grid property north of Kingaroy, and works installing solar pumps on farms. He says the majority of farmers he speaks to are not against renewable energy projects, but are confused by the “political footballing”. “We’re getting different messages from different political persuasions about the cost of electricity,” he says.

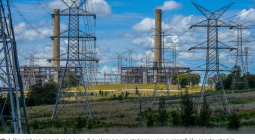

One of the political footballs is 30km south of Kingaroy. The Tarong coal-fired power station has been named as one of seven potential sites for the Coalition’s proposed nuclear reactors. The state LNP does not support the suggestion.

But on the streets of Kingaroy, locals tell Guardian Australia that if nuclear power is a substitute for the “reckless” renewable rollout, then it’s a great idea.

Afraid to speak up

Getting straight information about proposed developments is difficult.

In March, McCallum and Willmott delivered their presentation at Allora in Queensland’s Southern Downs region, after some landowners were approached by a windfarm developer. They were invited by the landowner and local president of lobby group AgForce, Graham Park.

Other landowners, who were in favour of the proposal, also attended. They moved to the back of the room as the crowd rallied behind McCallum’s rhetoric.

Down the road from Allora, in Greymare, a fight is brewing between farmers who are interested in playing host to a windfarm – which would earn them about $40,000 per turbine a year – and the owners of small hobby farms which are too small to host a turbine. No project has been approved for the area, but that has not stopped the vitriol.

“There’s angry people out there, it’s put us on opposing sides,” says Lindy Bennett, the owner of a small hobby farm who organised a snap meeting in opposition to a prospective windfarm.

Cynthia McDonald, a farmer in talks with a wind developer, and also a local councillor, says farmers “shouldn’t be held to ransom” by other landholders. “Once the turbines go on, they just become part of the landscape, you grow used to these things,” she says.

In a small community near Ipswich there’s another community meeting. A children’s petting zoo and community barbecue provide the backdrop for opposition to a proposal to build the largest battery storage project in Australia. Grant Kahler, who hosted the meeting on his lifestyle block, says their local campaign became more active after it was addressed by McCallum and Willmott in February.

The proposed project would be built on Ross and Steve Blanch’s dairy farm. “I’ve been working here since 1972, seven days a week, 365 days a year,” Ross says. “The last thing we want to do, at our age, is go through another drought like the last one.”

Blanch says he has spoken to almost 100 people in the region about selling his farm to the project developer and the majority say: “Ross, you gotta do what you gotta do”.

“I bet you there’s not one genuine, full-time farmer against what we are doing,” he says.