Why humans are drawn to the ends of the Earth

Despite the risks, costs and environmental concerns of extreme tourism, people are still drawn to potentially dangerous trips – but why?

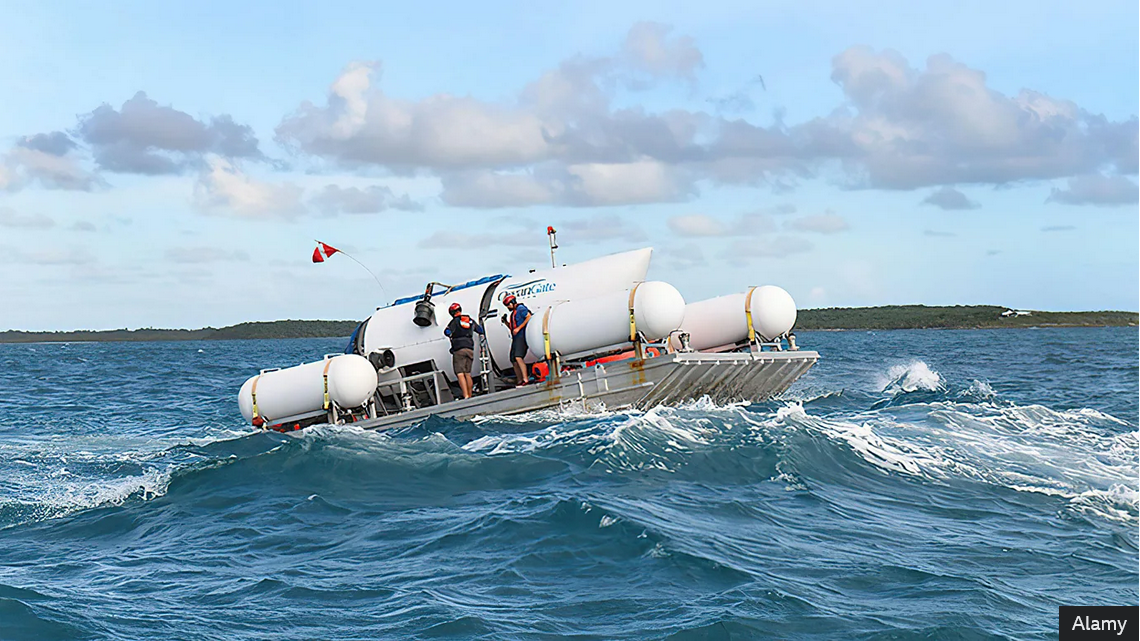

A year ago this week, the world focused its attention on the remote depths of the North Atlantic when the Titan sub, a cramped vessel operated by a video game controller, lost contact with its host ship on the sea's surface while descending to the Titanic wreckage. With just a 96-hour supply of oxygen, a frantic rescue mission unfolded.

A few days later, authorities confirmed that the poorly designed submersible had suffered a "catastrophic implosion" 3,800m below the sea, instantly killing the two-man crew and three passengers who had paid $250,000 apiece for their trip.

Anyone wondering whether the Titan's grisly fate might lead us to reconsider the safety and wisdom of extreme tourism got their answer late last month when a luxury real-estate billionaire announced plans to build yet another submersible to visit the Titanic site. The news came just nine days after the Blue Origin space tech company funded by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos launched its first crewed flight since one of his rockets crashed in flames in 2022. The six space passengers paid as much as $1.25m apiece for the nine-minute-and-53-second suborbital flight.

Yet, given the risks, costs and environmental concerns associated with extreme tourism, many are still questioning whether travellers should continue to venture to the edge of the Earth – or beyond.

"The extreme tourism sector is fraught with high costs, high danger and variable safety precautions," said Melvin S Marsh, who presented his research paper, Ethical and Medical Dilemmas of Extreme Tourism, to the International Conference on Tourism Research in Cape Town in March. Despite the interest in boundary-pushing travel, he noted "the ethical and legal considerations of some of the riskier activities have not yet caught up".

Still, Marsh and others say they don't expect anything to change.

"Nobody is surprised about any deaths that happen like this. You know it's going to happen," he added. "Very few people are even thinking about the issue."

Meanwhile, despite the extreme pollution caused by rocket launches, the number of private rocket launches has more than doubled since 2019, thanks in large part to billionaires Bezos, Elon Musk and Richard Branson's ongoing battle to see which of their commercial rocket companies achieves dominance.

Advocates say this new space race resembles the evolution of air travel. At first, daredevils and mavericks flew in planes, followed by wealthy passengers. Eventually the industry developed high-capacity jumbo jets that have made air travel affordable, ubiquitous and now the safest form of transportation on the planet.

According to Deana Weibel, a cultural anthropologist who studies religious pilgrimages and space tourism, the urge to explore distant frontiers – be it sailing across the sea or shuttling into space – is part of being human. And while some might dismiss 10-minute space trips as a shameless grab for bragging rights, Weibel says seeing the Earth from the blackness of outer space has a transformative effect on travellers – a documented experience known as the Overview Effect.

One of the most iconic environmental photographs ever taken – the famed Earthrise picture shot in 1968 by US astronaut William Anders, who died this month – not only inspired a sense of awe by giving us a perspective of humanity's place in the Universe, but also made it clear that when viewed from space, Earth has no borders. We all live on a tiny blue planet floating alone in a sea of blackness.

Weibel has interviewed astronauts who say their lives were transformed the moment they peered back at our planet from above.

"It forces you to recognise that you're on a planet, orbiting the Sun and there's an entire universe around us," she said. "It takes something that was sort of imagined and makes it glaringly, overwhelmingly real in a way you can't deny… It's the realisation of how fragile the planet is and how everything else around it is not livable."

Inspiring, yes, but back here on Earth, we've seen that when wealthy travellers take risks, everyone bears the costs.

The Titan submersible rescue effort cost the US government millions of dollars and stirred global interest. In contrast, a few days earlier, the Greek coast guard did little to help when a fishing boat packed with smuggled migrants sank in the Mediterranean, killing more than 600 people. Former US President Barack Obama was one of many noting the uneven media attention, which he said illustrated "obscene" levels of inequality.

Arun Upneja, dean of the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University, said one way to address the potential risks and costs of extreme tourism would be requiring companies offering these voyages to carry insurance making them liable for the risks and potential cleanup of an accident.

"Search and rescue insurance should be in some way mandatory… so society's not on the hook," he said.

But like Marsh, Upneja doesn't believe that the potential dangers of extreme tourism are enough to slow its momentum. In fact, he notes that the waiver signed by Titan passengers reportedly mentioned the word "death" three times on the first page. Price isn't likely to be a long-term hindrance either.

"Costs are bound to come down and make this available to larger groups," he added. "People have been doing it and they are going to [keep] doing it."

Yet, one notable change in the past year is that industry insiders seem to be taking the risk associated with potentially risky excursions more seriously. Two victims of the Titan accident were members of The Explorers Club, an international organisation founded in 1904 by Arctic explorers to promote scientific discovery and research. After the Titan incident, members formed a quick-response task force to assist in rescue and recovery efforts for those in dangerous settings.

The task force had previously assisted with various rescue missions, such as a hiker lost in a remote mountainous region of South America. Then earlier this month, the group mobilised to assist with the search for Michael Mosley, the doctor and BBC television host whose body was eventually found near a hiking trail in Greece.

"It's very much part of the Titan legacy," said Synnøve Strømsvåg, chair of The Explorers Club's Norway chapter and lead of the rescue task force. "If there's a problem, we put that out to the whole network. These people have networks and connections and ideas… We're not taking for granted that everything that can be done is done."

But Strømsvåg says that while improved safety and accountability is important, incidents like the Titan implosion shouldn't halt extreme travel. She notes that nothing can stop the urge for people to explore and push their limits – and nothing should.

"Humans have always been exploring. That's how we learned how the world works. That's how we've learned science. We underestimate the value of private business and individuals for moving that technology forward," she said.

Yet, others argue that people don't need to risk their lives soaring through the stratosphere or descending to the seafloor to have a meaningful travel experience.

Pauline Frommer, the editorial director of Frommer's travel guides, says spending obscene amounts of money for a trip doesn't ensure you'll have a meaningful adventure. On the contrary, it's likely to remove you from the people and cultures that make the world so wondrously diverse and therefore restrict how much of a meaningful and potentially transformational travel experience you may have.

"When you put your life at risk, you are cutting yourself off from the life of that destination. Sometimes these extreme adventures isolate you," she said.

Frommer says her most memorable travel experiences – be it an unexpected encounter with strangers or an early morning walk in a city as it awakens – may sound far more mundane than extreme, but that doesn't make them any less unforgettable to her.

She recalls visiting Taiwan and meeting a monk at a park. "I had a long, long talk. We started chatting about life, and his life and what it's like to be in a monastery," she said. "And to this day, I think about that. It was just a conversation."