Τα πυρηνικά απόβλητα κοστίζουν ακριβά στους φορολογούμενους.

These dumpsters of old nuclear waste are costing taxpayers a fortune

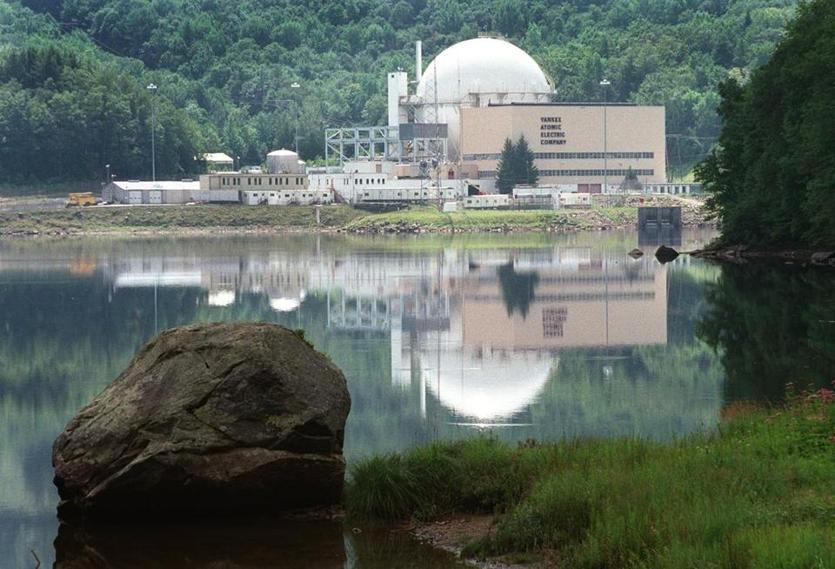

ROWE — The nuclear plant deep in the woods of this Western Massachusetts town stopped producing power 27 years ago when George H.W. Bush was still president. It was dismantled, piece by piece. Buried piping was excavated. Tainted soil was removed. But nestled amid steep hills and farmhouses set on winding roads, something important was left behind.

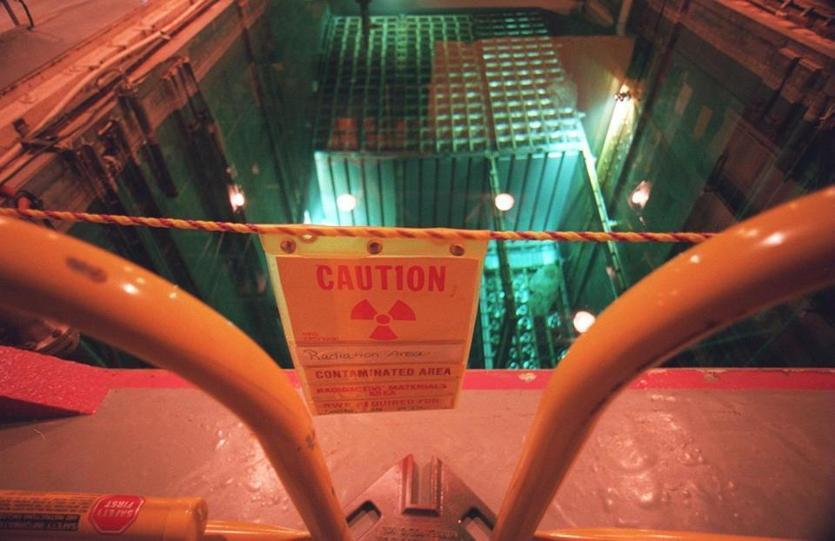

Under constant armed guard, 16 canisters of highly radioactive waste are entombed in reinforced concrete behind layers of fencing. These 13-foot-tall cylinders may not be much to look at, but they are among the most expensive dumpsters in the country, monuments to government inaction.

Lawyers for Rowe’s defunct plant and long-dismantled reactors in

Maine and Connecticut are poised to march into a federal courtroom in coming weeks and, for the fourth time in recent years, extract a huge sum of taxpayer money to cover ongoing security and maintenance costs. Taxpayers have already ponied up $500 million as a result of lawsuits filed by the plants’ owners, and they are poised to pay $100 million more this time.

Nationally, the US government’s failure to keep its vow to dispose of spent nuclear fuel and other high-level waste is proving staggeringly expensive. So far, the government has paid out more than $7 billion in damages for violating its legal pledge to begin hauling away nuclear waste by 1998.

And costs are expected to soar as more of the nation’s aging reactors close permanently: Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Plymouth, for instance, is slated to go offline by June. Eventually, the remaining staff may have the sole job of safeguarding the radioactive detritus.

By the Department of Energy’s own optimistic estimates, the government will be forced to cough up a whopping $28 billion more in taxpayer funds as a result of litigation in coming years.

Long before the 35-day partial government shutdown crippled Washington, the dug-in debate over where to dump the nation’s civilian nuclear waste set the radioactive standard for government dysfunction. For more than 60 years, government officials have tried to solve the problem, but plan after plan has collapsed amidst nationwide cries of “Not in my backyard!” So far, all officials have to show for the work is an enormous $10 billion-plus hole in Nevada that will probably never be used.

Instead of consolidating waste in one place, it has left material that is toxic for thousands of years at scores of current and former civilian nuclear plants. Neighbors fear the waste will stay permanently, siphoning money from other needs, thwarting redevelopment, and eventually posing a safety risk.

Senator Edward J. Markey, a longtime nuclear skeptic, said lingering nuclear waste tends to focus the attention of nearby cities and towns on a simple question: “When is this problem going to be solved? Or am I going to have a nuclear waste site in my community for the rest of my family’s life?”

The promise of nuclear power burned bright in 1960 when the Yankee Atomic Electric Co. first fired up its reactor in Rowe. But, even then, proponents of the new power source knew they were creating a problem: the super-hot, super-radioactive uranium fuel rods left over from generating power. Most plants dumped them in deep pools of water, but that was only a temporary solution.

By the early 1980s, as waste accumulated, Congress made this pledge: The Department of Energy would haul away nuclear plants’ spent fuel and other high-level waste starting by 1998 and the owners would pick up the tab, in part through a fee in customers’ electric bills.

The law was supposed to jump-start a scientific process to choose the best repository for waste. But not-in-my-backyard politics repeatedly got in the way. Who, after all, wants a national nuclear waste dump buried nearby forever?

Congress later zeroed in on a remote desert site called Yucca Mountain in Nevada, about 75 miles from Las Vegas.

But Nevada didn’t want the nation’s spent nuclear fuel either, and the state’s top politician, senator Harry Reid, the majority leader from 2007 to 2015, strongly opposed the plan. After the United States spent more than $10 billion drilling down into and studying the site, the Obama administration effectively killed Yucca around 2010. Congress has not restarted funding for the effort.

Proposals to create a consolidated repository to store the waste for an interim period in New Mexico and West Texas are moving forward. But those, too, face huge hurdles.

Meanwhile, electric ratepayers from New England, home to seven current and former nuclear power plants, have paid what is now an estimated $3 billion with interest into the fund to dispose of nuclear waste.

But the account has not brought its intended benefit.

Even with strong support for a permanent fix from the nuclear power industry, environmentalists, and local officials, Congress has remained deadlocked on a final resting place for spent fuel and other highly radioactive waste.

“It’s the sad story of government ineptitude,” said Andrew Kadak, who was chief executive of Yankee Atomic Electric for eight years, including during the Rowe reactor’s closure in the early 1990s. “There are technical solutions. . . . It’s the politics that is preventing implementation.”

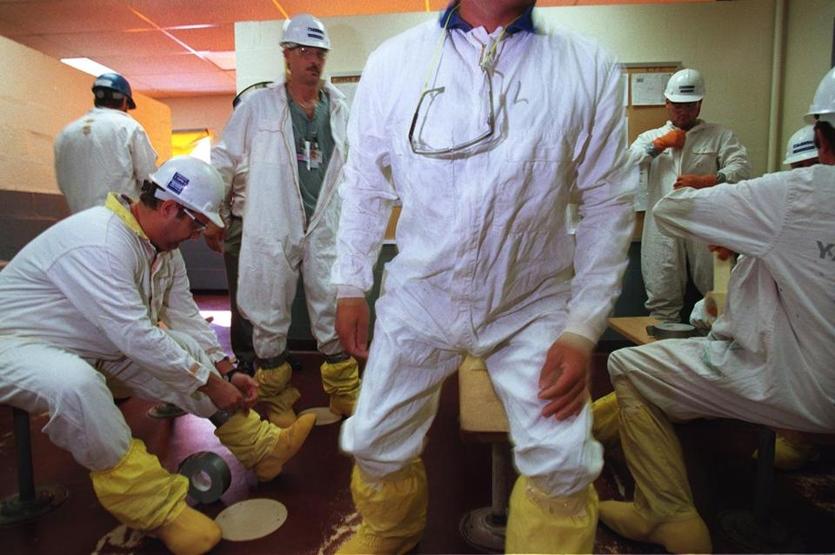

So nuclear plants continue to keep the waste on hand. And they continue to get reimbursed for payroll, security, supplies, and more, because the courts have found the government is in partial breach of its contract to haul away the waste.

In a twist, the government’s payments can’t come from that nuclear waste fund, a federal court ruled. Instead, it is taken from a separate pool of taxpayer dollars for court judgments and settlements of lawsuits against the government.

The latest suit from Yankee Rowe and the two other fully shuttered New England plants in Wiscasset, Maine, and Haddam, Conn., is set to soon go to trial and cost taxpayers more than $100 million.

And it probably won’t be the last lawsuit. Company officials say each plant spends about $10 million a year safeguarding its waste and maintaining corporate structures solely for that task.

Meanwhile, soon-to-close Pilgrim is getting ready to follow in Yankee Rowe’s footsteps, moving its remaining spent fuel from cooling pools to huge concrete cylinders, known as dry cask storage, by 2022.

So far, across the country, there haven’t been any serious accidents with the casks, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. But as the time frame for their use stretches out indefinitely, no one can be sure how long before the waste poses a threat.

The uncertainty also is forcing plant operators to plan for longer-term issues including climate change and rising sea levels. Officials at Pilgrim, which is oceanfront property, said last year that the plant will move its current cylinders to higher ground and place new ones there, too.

The NRC believes the casks should be safe for years to come, licensing their use for up to 40 years at a time.

The agency has ruled that, with proper inspection and maintenance, casks could last more than 100 years before the waste would have to be transferred to a new steel canister and concrete shell.

But Allison M. Macfarlane, a former NRC chairwoman, said there’s no guarantee the infrastructure will be in place to monitor them for safety.

“That assumes our institutions are robust and will last hundreds of years and I think that’s a poor assumption based on no evidence whatsoever,” Macfarlane said in the midst of the partial federal shutdown.

That is why, experts insist, a permanent subterranean repository like the one planned for Yucca Mountain is the only real solution.

“You should really put it underground where the risk is much lower and you don’t have to worry about institutional failures,” said MIT researcher Charles W. Forsberg, a chemical and nuclear engineer.

In the meantime, communities that host closed and closing nuclear plants face yet another cost: prime real estate that’s potentially locked up for generations.

State Senator Viriato M. deMacedo of Plymouth said, “We have a mile of oceanfront property where that plant is. Once it closes, it will never be able to be used as long as those spent fuel rods are there.”

Some still hope that politicians will find a final graveyard for the nuclear waste, and the bucolic valley where Yankee Rowe stood and the beach where Pilgrim stands are redeveloped.

But, after three generations of failed efforts to permanently dispose of the waste, another vision is more likely. Plymouth, where the Pilgrims made the West’s first permanent mark in New England, could be home to its last: 61 gigantic casks of nuclear waste forever overlooking the sea.

31 January 2019

Joshua Miller