After decades of profit, the oil and gas industry should split the climate clean-up tab

With its first-ever target for CO2 geological storage, the European Commission’s Net-Zero Industry Act has the potential to truly mitigate the effects of fossil fuels on the environment – but in order to be effective, the legislation needs to cover all oil and gas companies, write Kayla Cohen and Eli Mitchell-Larson.

Kayla Cohen is a Senior Researcher at Carbon Gap, an independent non-profit organisation focused on scaling up carbon dioxide removal in Europe, as a complement to emissions reductions. Eli Mitchell-Larson is Chief Science & Advocacy Officer and Co-founder of Carbon Gap, and an Associate researcher at Oxford Net Zero.

In 2022, while oil and gas companies reported record profits, Europeans felt the heat of skyrocketing energy bills and their hottest-ever summer. Extensive wildfires, deadly heat waves and severe drought ravaged the continent, jeopardising Europe’s agricultural production and citizens’ physical health.

Never has the widening gap between those profiting from and those paying for the climate catastrophe been so evident.

Now, the European Union is taking steps to shift some responsibility for cleaning up the climate mess onto fossil fuel companies with the new proposed legislation.

Article 18 of the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) requires oil and gas producers based in the EU to help develop geological storage for at least 50 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2030. That’s roughly equivalent to Hungary’s annual fossil fuel and industrial emissions.

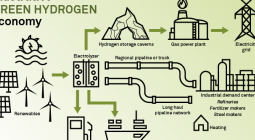

Carbon dioxide can be injected and durably stored in depleted oil and gas fields, among other sites. Capturing genuinely hard-to-abate emissions and locking them away is likely to play a key role in decarbonising Europe’s heavy industry. Likewise, sequestering CO2 pulled directly from the air will be essential to help the EU achieve its 2050 climate neutrality goal and net negative emissions thereafter.

This is the first time the EU has laid out legislation that could be interpreted as an extended producer responsibility for the fossil fuel industry. Just as many member states regulate tyre manufacturers to manage their end-of-product waste, the NZIA proposal would oblige oil and gas producers to kickstart an infrastructure to store their carbon dioxide waste product. Although significantly different in its design and application, this provision shares some DNA with the carbon takeback obligation policy proposal.

Obligating EU fossil fuel producers to deploy their own financial resources, technical expertise and organisational capacity to permanently store a portion of their product’s pollution could finally help reflect the true climate impact of oil and gas production in pricing.

However, some ambiguities and omissions leave Article 18 vulnerable to ineffective outcomes.

First, oil and gas providers could be obliged to actually fill the storage facilities they build, above and beyond developing injection capacity. After all, it’s the physical disposal of CO2 waste that producers should be responsible for and there’s as much sense in an unused storage site as building a bridge to nowhere.

This amendment would incentivise fossil fuel companies to procure CO2 captured from energy-intensive sectors with unavoidable emissions as well as carbon removal providers to meet their obligation.

Second, the European Commission should clarify that oil and gas producers must pay for the lion’s share of what’s needed to meet the 2030 target and that financing CO2 storage will not eat into public funds. This is crucial if Article 18 is to become a fully-fledged producer responsibility policy, rather than form the basis for a new revenue stream for fossil fuel extractors.

Third, the EU should evaluate the implications of extending responsibility to meet the 2030 target to all suppliers of oil and gas to Europe, not just domestic producers.

The EU imports the vast majority of its oil and gas to meet its consumption demands, with crude oil import dependency reaching an all-time high in 2020 at 97%. If the obligation only falls on domestic producers, they will bear the costs alone, which could cause domestic production to dip as imports surge, with no assurances that EU fossil fuel consumption declines overall. This could lead to worse environmental outcomes and endanger Europe’s climate progress.

Ultimately, all fossil fuel suppliers must shoulder responsibility, if not through this Act than through some other means.

Fourth, the Commission must specify penalties for non-compliance and establish a public registry of all contributions to Europe’s carbon dioxide storage. Such transparency will enable regulators and third-party watchdogs to monitor progress. This registry should note where the stored CO2 comes from – whether it was captured from the air via carbon dioxide removal or at point-source via carbon capture and storage.

Carbon dioxide removal must not detract from the urgent task of cutting emissions. The EU must spell out which sources of CO2 emissions should not be counted towards the Union’s storage target. Rather, CO2 derived from genuinely hard-to-decarbonise industrial emissions should be prioritised, and the EU’s carbon removal needs adequately catered for to durably sequester residual and historical pollution.

Scaling CO2 storage is one of many ways the oil and gas sector can contribute to climate mitigation efforts, in addition to setting binding emission reduction targets and shifting its long-term investments to renewables.

At a time when the fossil fuel industry is shirking its responsibility to act on solving the climate crisis, governments must step in to require their adequate contribution to a problem partially of their making. Preserving the NZIA’s Article 18 and strengthening its producer responsibility ethos is a step in the right direction, setting a global precedent Europe could be proud of.

cover photo:The Net-Zero Industry Act's Article 18 proposes extended responsibilities for the fossil fuel industry. EPA-EFE/CAROLINE BREHMAN