They cleaned up BP’s massive oil spill. Now they’re sick – and want justice

After 18 rounds of chemotherapy, Samuel Castleberry is tired.

If it were up to him, he’d still be working his trucking job. The 59-year-old was making a decent living and felt fit. But in June 2020, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, which has already spread to his liver. Now he gets out of breath wheeling his garbage can to the curb at his home in Mobile, Alabama.

Floyd Ruffin, 58, grew up around horses in Gibson, an unincorporated community in south Louisiana. In 2015, he was also diagnosed with prostate cancer, which has made it uncomfortable for him to ride. Before his prostate was removed, he had dreams of having more kids.

Terry Odom, 53, lies awake at night in her home in San Antonio, Texas. She worries that she, too, has cancer. As a chemist she’s used to finding answers, but she can’t figure out why her health is deteriorating. She’s emailed dozens of doctors and researchers in search of answers. “You feel like you might die before your time,” she said.

A single disaster unites the three of them. Thirteen years ago, they helped clean up BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the largest ever in US waters. They rushed toward the toxic oil to save the place they loved, joining forces with more than 33,000 others to clean up our coastlines. Now, they have active lawsuits against BP, saying the company made them sick.

Since the cleanup, thousands have experienced chronic respiratory issues, rashes and diarrhea – a problem known among local residents as “BP syndrome” or “Gulf coast syndrome”. Others, like Castleberry and Ruffin, have developed cancer.

The valor displayed by cleanup workers was comparable to the heroism of first responders during the 9/11 terror attacks, who ran to the World Trade Center to save people and breathed in toxic dust and fumes, said the Alaska toxicologist Riki Ott, who became involved in advocating for oil spill cleanup workers after the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska. “What resident and professional oil spill responders do is exactly what professional firefighters and emergency responders everywhere do: put their lives on the line to protect ours,” she said.

But while those who responded to the deadliest single terror attack in American history have been rightly cemented into public memory, coastal workers in some of the poorest parts of the country – those who laid their bodies on the line following the worst industrial catastrophe in a generation – have faded away, unrecognized and left to fight for themselves.

On 20 April 2010, a rig contracted by the oil and gas company BP to drill in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico blew up, spewing more than 200m gallons of oil.

Eleven workers were killed that day, but some argue the spill’s death toll could be far higher – and underreported – as cleanup workers soon started to develop illnesses they claim are linked to exposure to toxins in the oil as well as Corexit, the chemical that was used by BP to break up oil slicks.

During the 87 days that oil gushed from the seafloor, lower-income workers in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida picked up tar balls from beaches, sopped up oil with absorbent booms, decontaminated boats, and burned oil on the water surface. They also rescued wildlife, including oiled birds, sea turtles and dolphins.

Some were Vietnamese fishers put out of work when Gulf waters were closed to shrimping. Others were Cajun construction workers and Black cowboys. Most had livelihoods that depended on the Gulf. Those contractors worked the spill for weeks or months at a time, and about 30% of them had annual household incomes under $20,000, according to demographic data collected by the National Institutes of Health.

BP told many of its cleanup workers that they did not need to wear breathing protection because the toxic components of the oil had evaporated or were broken down in the waves, according to the company’s safety briefings. Despite receiving advice from the federal government to conduct biological monitoring by measuring toxins in the cleanup workers’ blood, skin or urine, BP didn’t collect evidence that could have shown whether toxins contained in the oil had entered workers’ bloodstreams, according to plaintiffs’ attorneys.

In 2010, BP ran a huge PR campaign to convince the public that the Gulf would recover. While the smell of oil and Corexit was still in the air, BP was already building its legal defense against the very workers it claimed were repairing the spill’s environmental damage, according to new evidence reported for the first time by the Guardian.

There is no class-action settlement for the cleanup workers and coastal residents who fell ill years after the spill. Due to the terms of an earlier settlement, they must sue BP individually to be compensated for their chronic injuries, and many of the cases are under a court order that prevents them from seeking punitive damages.BP declined to comment on a series of detailed questions from the Guardian, citing the ongoing litigation. A district court judge found that the company that made the Corexit used during the BP spill, Nalco Holding Co, was not liable for medical claims related to the use of its product during the spill because the use was approved by the federal government, according to court documents. Ecolab Inc purchased the company in 2011 but later sold it to a subsidiary, Corexit Environmental Solutions LLC. (When contacted by the Guardian, Corexit Environmental Solutions said it was never involved in any decisions related to the use of its product in the Gulf.)

BP paid $65m to 22,588 people in the earlier medical settlement for short-term illnesses, less than $3,000 each on average, according to a 2019 claims administrator update. The company also spent more than $60bn to resolve economic and natural resources claims from the spill as well as civil penalties under the Clean Water Act.

But in the cases of long-term health problems, the odds have not been in plaintiffs’ favor.

The oil and gas multinational has taken a “scorched-earth” approach to each lawsuit, said the attorney Jerry Sprague, who has filed about 600 medical cases against BP. According to eastern district of Louisiana court records, nearly 5,000 cases had been filed as of January 2020.

The company has hired experts in hundreds of cases and in certain instances deposed plaintiffs and their doctors for hours, combing over their medical records, tax returns and employment files.

“BP wants us to know they will fight these cases to the end,” Sprague said.

In court, BP has argued that without biological evidence, workers and coastal residents cannot prove their illnesses were caused by the oil spill, despite research linking exposure to the spill with increased risk of cancer and higher rates of long-term respiratory conditions, heart disease, headaches, memory loss and blurred vision. Thousands of cases have been dismissed, according to plaintiff lawyers. Only one known case has resulted in settlement.

“It’s by far the most gut-wrenching public health disaster that I’ve ever been exposed to,” said Tom Devine, the legal director for the Government Accountability Project, which has produced several reports based on interviews with sick cleanup workers. “What’s particularly frustrating is BP doesn’t care,” he said.

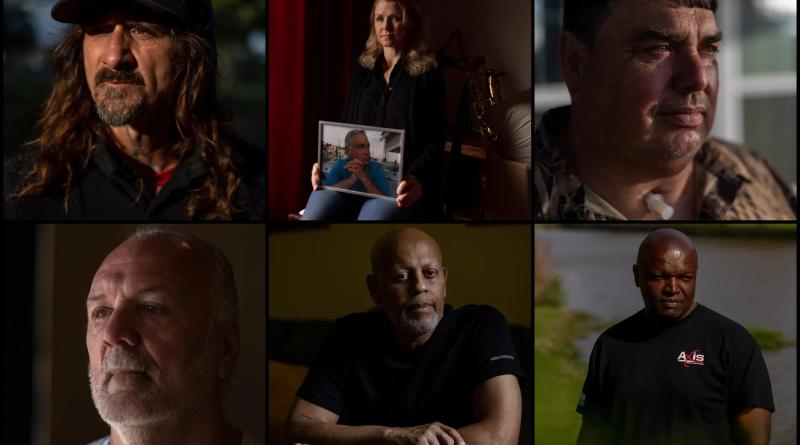

The Guardian interviewed more than two dozen former cleanup workers in the reporting of this story. Many had never spoken publicly before.

Frank Stuart Sr, a father of six, described the cleanup work as a “crusade”.

He led a team of boats to stop oil from washing into an estuary in south Louisiana, between Lafitte and Grand Isle. They worked 15-hour days for months. “This was a crusade to make sure that we protected the wetlands. We made sure that if there was a fisherman or crew member who needed work, we put them to work so they wouldn’t lose their home. They wouldn’t lose their car. They had a way to eat,” he said in a video recorded by his daughter, Bailey Stuart, in 2017.

The following year, Frank Stuart was diagnosed with myeloid leukemia, a rare cancer. His condition quickly deteriorated. His wife of 22 years, Sheree Kerner, sat next to his hospital bed on her laptop, trying to understand what had made her husband sick. Her search led her back to Stuart’s exposure to the toxic combination of BP oil and Corexit.

On 19 April 2018, the day before the eighth anniversary of the BP oil spill, her husband died at home in her arms.

“It’s just egregious they could get away with murder,” Kerner said of BP. She has filed a suit against the oil company for her husband’s death.

To get a fuller picture of the illnesses cleanup workers and coastal residents say were caused by the spill, the Guardian analyzed a random sample of 400 lawsuits filed against BP. Sinus issues are the most common chronic health problem listed among those who have sued, followed by eye, skin and respiratory ailments. Chronic rhinosinusitis, a swelling of the sinuses in the nose and head that causes nasal drip and pain in the face, was the most common condition.

Most of the plaintiffs were cleanup workers. One was a first responder and one lived near where oil washed ashore in Gulfport, Mississippi. About 2% of the plaintiffs have cancer, but public health advocates believe more are likely to be diagnosed in the years to come.

“Your results are pretty much what a Yale University study found 13 years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill,” Ott said. “I believe that more oil spill-related cancers will develop over the years.”

John Pabst, 64, also links his cancer diagnosis to his cleanup work during the spill.

It was filthy work. The stench of burning oil wafted through the air, and the humidity and searing temperatures left those out on the water exhausted, sweaty and dehydrated.

Pabst remembers hauling soft boom lines 200ft long from the marshes in his small shrimping boat, the thick, greasy, diesel-like smell of Corexit and oil lingering around his vessel. But Pabst, a barrel-chested and broad-shouldered man whose family has caught shrimp off the Gulf coast for three generations, took pride in the work. The pay was generous. The cleanup efforts were imperative to preserve his way of living for future generations.

“It was a dirty, nasty, stinky job,” he recalled one recent morning sipping coffee near his home in Chalmette, in south-eastern Louisiana. He would go through three packets of baby wipes a week out on the water, washing sweat from his face, leaving his eyes stinging and his head throbbing throughout the 11-hour shifts.

The headaches and nausea became chronic in the aftermath and then, in 2017, he was diagnosed with lymphoma in his eye, which he claims was caused by months of exposure to toxins during the cleanup.

Rounds of radiation therapy followed. The process, he said, left him with claustrophobia and PTSD, and lingering worries about if and when the cancer would return.

“You always wonder: was it worth the money I made?” he said, his case still pending in federal court. “We made 10 grand every other week for three or four months [during the cleanup]. But sometimes we’d make more than that shrimping.

“But now, every time something happens with my health, you wonder: is this part of the cancer?”

Last fall, Sprague, the attorney, filed a motion alleging that BP had a duty to collect and preserve data on cleanup worker exposure levels, but it didn’t do so to help its defense against future litigation.

Oil was still gushing into the Gulf of Mexico when three federal entities, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Research Council all submitted plans suggesting that BP biomonitor cleanup workers, according to emails uncovered during discovery.

Biomonitoring is a way to measure chemical exposure levels by testing bodily fluids for toxins repeatedly over time. This type of monitoring is helpful in determining causation of acute and chronic illnesses. But instead of monitoring workers’ bodies, BP spent more than $13m monitoring air. In an email to his colleagues, John Howard, the director of National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, wrote that air monitoring alone doesn’t capture all of the ways that toxins could enter workers’ bodies.

In an email dated 27 June 2010, found during discovery, he wrote:

Since air sampling does not reflect total exposure, and total exposure may be more associated with longer term health effects, the continuation of our approach without incorporating biomonitoring (1) represents only a partial approach to determine exposure; (2) leaves us scientifically incomplete; (3) leaves us unable to address the concerns of those who are in the media now saying that harmful exposures are occurring despite negative air sampling results.

He went on to say that the lack of biomonitoring would also impair researchers’ ability to conduct long-term health studies. Howard did not respond to requests for comment.

To conduct the air monitoring, BP hired a company called CTEH. In June 2010, two members of Congress wrote a letter to BP highlighting the company’s decision to contract with the consulting firm, which has a track record of working with companies to downplay the risks of major pollution events for which they are responsible.

Murphy Oil hired CTEH in 2005 to perform testing after the company’s refinery was flooded by Hurricane Katrina and leaked 1m gallons of oil into 1,800 homes in Meraux and Chalmette, Louisiana. The US congresswoman Lois Capps and senator Peter Welch wrote that hiring CTEH was “yet another misstep at the expense of the public’s health”.

CTEH was recently hired by Norfolk Southern, the operator of the train carrying toxic chemicals that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio. Though CTEH said its testing showed no harmful chemicals in the homes of nearby residents, ProPublica and the Guardian talked to several experts who said the tests were inadequate and couldn’t prove that residents were safe.

During discovery, Sprague’s firm found a chain of emails among BP’s internal medical team from 31 July 2010 in which they discuss the company’s air monitoring efforts. “Although we are documenting zero exposures in most monitoring efforts, the monitoring itself adds value in the eyes of public perception, and zeros add value in defending potential litigation,” wrote John Fink, a BP industrial hygienist.

For Sprague, this was a critical revelation.

“You have an admission right there that BP is going to do air monitoring not because they’re trying to find dangers in the air but to defend against future litigation,” Sprague said about the email. “The scientists are saying we should do biomonitoring. BP ignores it. How does that look when you know they’re still going to do air monitoring to defend litigation?”

BP declined to answer questions on its toxic exposure monitoring during the disaster.Jorey Danos keeps reminders of the disaster scattered around his one-acre homestead in the small Cajun town of Golden Meadow, Louisiana. There are jars of brown seawater that contain oil from the spill still floating at the top; suitcases full of his legal documents that bulge with paper and his ID cards from four months working on the cleanup, his photo now faded and scratched.

Danos was 31 when he stepped forward to address the spill. Now in his early 40s, he’s already taken retirement, suffering from a variety of long-term conditions he attributes to the Deepwater disaster, including chronic abdominal and stomach pain and loss of memory.

His recollections of work out on the Gulf remain vivid, however: pelicans smothered in oil, dolphins spewing oily water from their blowholes. “It was just a total disaster,” he said. “Apocalyptic.”

His suit for medical damages was dismissed last year, records show.

“It’s not about the money any more,” Danos said as he sat in his backyard looking through the paper remnants of his case. “I wanted a guilty verdict, and I wanted them to explain why they had to use toxic chemicals known to be harmful to humans.”

Documents suggest that not much was done by BP to prepare cleanup workers for the toxic risks associated with the job. Recently released BP training modules, obtained in discovery by the Downs Law Group, a Miami-based law firm involved in more than 100 active spill cases, have led the firm to argue that cleanup workers received minimal briefing on toxic hazards.

Instead, the warnings appear to have focused on heat exhaustion, insects and the risks of trips and falls. In one module, prepared for shoreline workers, the risk of exposure to dispersant is characterized as “very unlikely”, adding that the “health effects would be similar to exposure to any mild detergent”.

“Dispersants used in the Gulf have no ingredients that cause long-term health effects, including cancer,” the slide reads.

The module also assures shoreline workers they should not need to wear protective breathing gear because they would be exposed only to less hazardous weathered oil, rather than more toxic crude oil. But BP’s own internal safety documents say that even weathered oil still poses a hazard if it contacts the skin, potentially causing skin, eye irritation and diarrhea. And wearing safety goggles, Tyvek protective suits, rubber boots and gloves when in contact with the substance “might not be adequate”, the document states.

Another training module assures cleanup workers that by the time oil reaches the shore, it will have been “subject to time and distance ‘weathering’ before impacting shoreline”.

BP declined to answer questions about its training of cleanup workers.

James “Catfish” Miller said he had received almost no protective clothing at all when he began his work for BP about a month after the catastrophe began.

“I said it about 9,000 times: ‘Where’s our boots and gloves, our Tyvek suits?’ They didn’t have none to give us,” he recalled, remembering his early days working off the coast of Biloxi, Mississippi. “Zero. Zilch-o. But we didn’t complain. The pay was good.”

The slicks would run for miles, coating his shrimp boat in thick smears of a tar-like substance. He claimed to have received so little training that one day early on, when rope was caught in the propeller of his boat, he jumped into the polluted water to cut the rope with no skin protection, treating the incident as he would on any normal day shrimping out in the gulf.

His symptoms began soon after – nausea, headaches, diarrhea.

He nicknamed his deckhand “the canary” because he was the first to pass out. But soon after, Miller did too. About a month and half into the work, he was hospitalized after his esophagus began to bleed during chronic vomiting. He was bed-bound for months and lost over half his body weight, he recalled.

“I thought I was going to die. It was chemical poisoning.” he recalled. “I just couldn’t bounce back.”

The recovery took years and he has battled spates of anxiety and depression ever since. The experience led to the breakdown of his marriage. Miller’s lawsuit for long-term medical damages was dismissed in September last year, according to records.

“I think we’ve just been robbed of our health in our life,” he said.

Within a month of the spill, BP began running an aggressive and expansive local PR campaign, placing frequent advertisements in local newspapers around the Gulf coast over the next year. The company’s army of local cleanup workers were placed front and center.

“We have organized the largest environmental response in this country’s history,” proclaimed one advertisement in the Advocate newspaper on 3 June 2010. “More than 3m feet of boom, 30 planes and over 1,300 boats are working to protect the shoreline. When oil reaches the shore, thousands of people are ready to clean it up.”

The campaign ran under the banner: “We will make this right.”

Over a decade later, the phrase would be repeated almost verbatim as the slogan to another campaign promoting the corporate response to the toxic disaster in East Palestine, Ohio.

The Louisiana chemist Wilma Subra understood the potential for the BP spill to result in a public health disaster. She advocated for cleanup workers to be given respirators and other personal protective equipment during the spill response, with little success.

Soon, she noticed something else: “BP signed agreements with every technical expert they could get their hands on,” she said. “You could clearly see it was aimed toward making them look good and not presenting the real negative impacts of it.”

In addition to trying to control the public narrative, BP put researchers on its payroll and had a role in reviewing certain scientific research about the impacts of the spill. The Downs Law Group uncovered an internal BP spreadsheet in discovery that appears to track the company’s review process in the publication of 29 scientific studies on a variety of topics, including the spill’s toxicity and impacts on birds, fish and oysters.

The spreadsheet, last updated by BP in 2013 or early 2014, shows the company had several steps in its approval process, including “tech review” “sent to author for changes”, and “final legal/BP review”. Annotated next to a study about the impacts of oil and dispersant on oysters, the company notes: “Back with author for changes.”

Not all of the studies listed in BP’s research tracker were published with disclosures indicating that BP provided comments, suggested revisions and performed a legal review of the contents. “BP influenced the science,” said David Durkee, an attorney with the Downs Law Group. “I think it’s becoming more apparent, at least through these documents, that BP had an active influence in trying to put a finger on the scale.”

But other studies published in the past five years have linked exposure to the 2010 BP spill with a slew of health problems, including heart conditions, neurological symptoms and an increased rate of births of premature and underweight infants. These health studies build upon those from the other spills, such as the Prestige oil tanker spill off the coast of Spain in 2002 and the Hebei Spirit oil tanker spill in South Korean waters in 2007.

Health effect research on the Hebei Spirit Oil Spill was given the acronym Heros to denote the cleanup workers’ efforts to fight back the oil as it washed ashore, Ott said.

“They’re acknowledging that the participants in their studies are heroes,” she said of the South Korean cohort study name. The province in South Korea where the spill washed ashore built a memorial hall to commemorate the cleanup effort.

For two years, 11 life-sized steel figures stood in the neutral ground of a busy New Orleans street to memorialize the men who died when BP’s rig exploded in 2010. Those sculptures are no longer there, and the BP oil spill cleanup workers were never memorialized. “Individuals are being victimized twice, the way I see it,” Ott said.

One person has won a settlement so far: Captain John Maas.

Maas had just received his boat captain’s license when the oil began washing ashore in Mississippi. He and his girlfriend at the time went out in search of oiled birds and turtles to rescue. Four months later, she died from cancer. “That sort of lit a fire under my ass,” Maas said.

He filed a suit against BP for his own health issues resulting from the spill, chemically induced asthma and restrictive lung disease.

Maas was deposed by BP twice, totaling 15 hours of questioning, he recalled. BP also deposed his doctor, Dr Charles Wray, prodding him to say that Maas’s asthma was actually caused by his obesity, not the oil spill. But, according to transcripts, Wray was unswayed and the company ultimately settled the suit. Both Maas and his attorney, William “Ken” Burger, were required to sign confidentiality agreements limiting them from speaking publicly about the terms of the settlement.

“I have no illusion that this is over. None … One little dumbass ninth-grade-educated captain beat them. But that’s not the real story,” Maas said. “The real story is how everyone else lost.”

Dr Veena Antony, a professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, was also deposed in the Maas case. Breathing in even a small amount of Corexit can cause damage to lung tissues, and make the tissue more permeable to toxins, she said. Like a game of Red Rover, the first breath of dispersant breaks open the cell barrier, allowing more toxins through in the next breath. “I think that the bottom line is that people suffered in the end,” she said. “To me that suffering is unacceptable. We should recognize that in times of emergencies the No 1 goal needs to be protection of human health.”be protection of human health.”

In March this year, the Biden administration gave the green light to a controversial drilling project in Alaska and leased 1.6m acres in the Gulf of Mexico to energy companies. But the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has failed to enact policy changes since the 2010 BP oil spill to protect future cleanup workers. In 2015, the agency issued a proposed rule to incorporate the lessons learned from the BP spill under the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan, the US government’s blueprint for responding to oil spills and other toxic chemical releases. But the rule was never finalized.

In 2020, the Alert Project, an advocacy group founded by Ott, sued the EPA for its failure to update its regulations on the use of chemical dispersants during oil spills.

A US district court ordered the agency to publish its updated policy by 31 May of this year. The American Petroleum Institute tried to intervene in the case, but was denied by the court. Still, environmental groups say the EPA’s proposed rule is not protective enough and doesn’t consider research published in the past several years showing the human health risks of dispersants.

“These are all baby steps. They’re not going to prevent future tragedies,” said Devine, with the Government Accountability Project. “The oil industry will basically have a blank check to use Corexit over and over again.”

Castleberry, Ruffin, Odom and many others interviewed by the Guardian say they are still waiting for justice – and waiting to be heard

When Castleberry found out he had cancer, he thought it was God’s way of punishing him for his mistakes. “I just figured it was something that I did somewhere down the line,” he said.

He has since come to believe that his cancer is not the product of karma, but of his exposure to the spill. He says BP should pay for their wrongdoing. “I’m a very firm believer that if you do wrong, you’re deserving of the consequences or whatever follows,” he said.

Ruffin is checked regularly by his doctors to make sure his prostate cancer has not returned. “So now it’s in the back of my mind that this stuff can pop up at any time,” he said. While he can’t forget how the spill has affected his body, he says the public seems to have moved on. “Now that the beaches are pretty much back to normal as far as the eye can see; those that are sick are being forgotten,” he said.

Odom was laid off from her job at a chemical manufacturing plant near Pensacola, Florida, before the spill hit. She was having a hard time finding something else to pay the bills, which is why she took a job as a safety officer during the BP spill response. She was in a Polaris four-wheeler on the beach when her skin broke out in little bumps. “Like I was dunked in a vat of ants,” she said.

The next day she bought herself some long-sleeved shirts to wear to work. When other cleanup workers suffered from heat exhaustion, she took them to a mobile medical trailer to be looked over. But, she said, she was never told to watch out for signs of toxic exposure. Her co-workers were skeptical that what they were doing made sense.

“We were there to assure the public that everything was good and everything was safe and that everything was under control,” she said. “And that just was not true.”