Extreme heat could put 40% of land vertebrates in peril by end of century

Study shows ‘disastrous consequences for wildlife’ if human-caused emissions push global temperatures up 4.4C

More than 40% of land vertebrates will be threatened by extreme heat by the end of the century under a high emissions scenario, with freak temperatures once regarded as rare likely to become the norm, new research warns.

Reptiles, birds, amphibians and mammals are being exposed to extreme heat events of increasing frequency, duration and intensity, as a result of human-driven global heating. This poses a substantial threat to the planet’s biodiversity, a new study warns.

Under a high emissions scenario of 4.4C warming, 41% of land vertebrates will experience extreme thermal events by 2099, according to the paper, published in Nature.

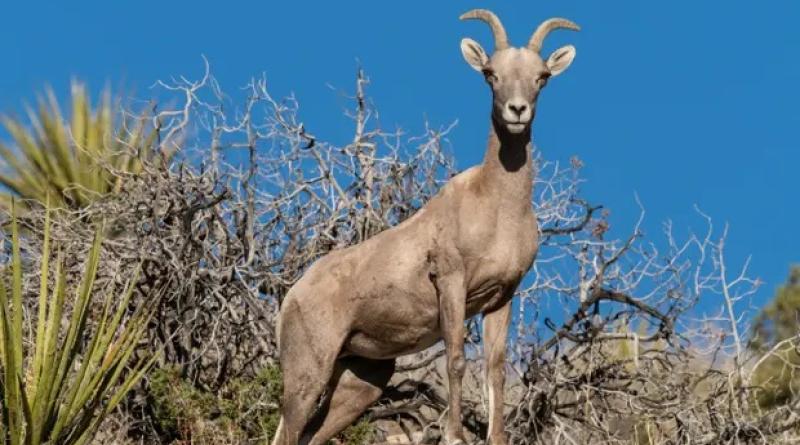

In worse affected regions, such as the Mojave desert in the US, Gran Chaco in South America, the Sahel and Sahara in Africa and parts of Iran and Afghanistan, 100% of species would be exposed to extreme heat. It is not possible to say if these areas would be uninhabitable, but it is likely that more species would become extinct.

Researchers mapped the effects of extreme heat on more than 33,000 land vertebrates by looking at maximum temperature data between 1950 and 2099. They considered five predictions of global climatic models based on different levels of greenhouse gas emission, as well as the distribution of terrestrial vertebrates, to work out how exposed animal populations would be.

“A couple of studies have shown recent climate warming trends match the 4.4C scenario much better than the other scenarios,” said lead author Gopal Murali, who was at Ben-Gurion University of Negev, Israel when he carried out the research. “We wanted to highlight the disastrous consequences for wildlife if we end up with a high, unmitigated emission scenario.”

Amphibians and reptiles were most affected, with 55% and 51% respectively likely to experience extreme heat events by the end of the century, compared with 26% of birds and 31% of mammals. Amphibians and reptiles are most vulnerable because they generally live within smaller temperature ranges.

Under 3.6C of warming, 29% of terrestrial vertebrates will experience extreme heat events, according to the report. This falls to 6% if warming is limited to 1.8C. “Deep greenhouse gas emissions cuts are urgently needed to limit species’ exposure to thermal extremes,” the researchers wrote.

Heat stress causes dramatic die-offs and can wipe out entire ecosystems, as happened in the 2021 heatwave along Canada’s Pacific coast, which experts estimate killed more than one billion marine animals. Murali said: “Heatwaves have become frequent. We see them every summer, with new records set all the time, and they have drastic impacts on wildlife. They can wipe out entire ecosystems overnight. But no large-scale studies have looked at how such extreme temperature events are going to affect biodiversity in the future.”

Extreme temperatures kill more than 5 million people a year globally, with heat-related deaths continuing to rise, research shows. “If we follow the current trends, the future is bleak,” said Uri Roll from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

While humans are able to shelter, and many can drink as much as they want and refrigerate their food, “this is obviously impossible for animals”, said Roll. “Ultimately, this will greatly affect many species – and this is just one facet of the many changes that are expected. We are not looking at changes of habitat or an increase in invasive species, or changes in rainfall [in the study]”

Prof Nathalie Pettorelli, an applied ecologist from the Zoological Society of London, who was not involved in the research, said the report provided “a good estimate” of the pressure that extreme heat may pose to land vertebrates by the end of the century, but added that it “fails to look at conservation status in relation to exposure. Taking this into account would help identify areas that are both likely to be hotspots for extreme heat events in the future and where things are already not looking good now, which would help prioritise action.”

Dr Ryan Long, associate professor of wildlife sciences at the University of Idaho, who was not involved in the research, said: “The authors make a compelling case that if current levels of emissions continue unchecked, a large percentage of the planet’s fauna will face unprecedented temperature extremes by the end of the century, especially in mid-latitude deserts, shrublands and grasslands.”

COVER PHOTO: A female desert bighorn sheep in the Joshua Tree National Park, California. Such areas would be among the worse impacted if global emissions are not cut. Photograph: Michael S Nolan/Alamy