Outlook? Terrifying: TV weather presenters on the hell and horror of the climate crisis

What is it like to have a front row seat for the worst show in the world? Four meteorologists describe how they are explaining the reality to viewers – and coping with it themselves

Tuesday 19 July 2022 is a day that will stay with Ben Rich for ever. “I got up and immediately checked the weather observations to see what was going on,” he remembers. “Then I went to work for my shift. The station was really hot, the train was really hot, and I remember having this moment. I got a bit emotional about it, to be honest. I thought: this is huge. And if it can happen once, why can’t it happen again?”

That was the day last year when the temperature in the UK surpassed 40C (104F) for the first time ever. Rich is a BBC weather presenter and meteorologist. “In my training, which was only about 10 years ago, I was led to believe that 40C in the UK was nigh on impossible, because there are all sorts of factors that should stop that from happening, not least the fact that we are surrounded by ocean. It should be too moist for temperatures to get that high.”

It didn’t come out of the blue – the computer models had been predicting it for a couple of weeks – but still it didn’t seem possible. “We were looking at it, going: no, this isn’t realistic, it’s not going to happen,” says Rich. Then, in the office, he watched as the temperature continued to rise. “There were stories of wildfires in east London and other places, the train network went down, there were reports of runways melting at some airports. All this was happening at the same time.”

As well as a meteorologist, Rich is a journalist: he worked on news before turning to the job he dreamed of doing as a kid. Of course, he knew this was a big story: he was getting interviewed on TV in Australia and the US – places much more used to extreme weather events. He found himself experiencing a mix of emotions. “The excitement of the story, how busy we were at work, but also that sense of real doom.”

Knowing and understanding what’s going on is one thing, but a whole new level of awareness comes from actually experiencing something. “I think the human condition is that to really get your head around a problem you have to be able to see it and feel it,” he says. “That was a real watershed moment, when the climate crisis was clearly happening to us, there and then. It felt to me that was a marker that something had fundamentally shifted in what the weather is capable of – and in our climatology.”

Switching channels, the ITV meteorologist Laura Tobin, who does the weather bulletins on Good Morning Britain, was also on duty that day. Like Rich, she had been watching the models with a mixture of incredulity and dread. “I remember when I did my first bulletin on that Tuesday morning I forecast that we would break 40C. Then when I sat down and chatted to my producer, I had tears in my eyes. Something I had thought would be a reality in the future was a reality that day. We shouldn’t be reaching these temperatures – it would be impossible to without climate change.”

I’m talking to four weather presenters and meteorologists about what it is like to have a front row seat at the worst show in the world: the climate crisis. Of course, weather is not the same thing as the climate: one happens over days, the other decades. But, as Clare Nasir puts it: “Climate impacts weather.” Nasir – who presents on Channel 5 as well as working at the Met Office (though views she expresses here are hers, not its) – says it has become easier to get this across in the past five or six years. “The onset of something called attribution studies has made our messaging easier and clearer. We are able to communicate now what we have been seeing and feeling and understanding for a lot longer.”

She explains how scientists have learned to detect a climate-change footprint in a particular weather event (extreme heat, rain, storms, etc) “by running the computer models with the scenario that has just happened but with lower amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to see if you could actually squeeze out that temperature, or that amount of rainfall. They then go back and put in a lot of different scenarios so they can calculate the likelihood of this event happening because of climate change. They can put a number on it – say, for example, it’s 100 times more likely this event has occurred because of climate change.”

And that is something that has changed about the job of weather presenter. It’s now more than sticking cut-out suns and clouds on maps with a smile; it’s about communicating and explaining things that are important.

My final presenter, Kait Parker, a meteorologist and climate reporter for IBM’s The Weather Channel – talking to me on a video call from Atlanta, Georgia – agrees that the job of communication has become more important. The US’s weather events, like its everything else, are bigger, so a large part of Parker’s job is warning of danger. “You constantly question: am I doing this well enough? Am I saving lives with this information? When you add a threat multiplier like climate change to those already dangerous storms, how do I communicate this greater risk? You question whether you are doing it effectively, because it feels as if lives depend on whether you do it well or you fail at it.”

It wasn’t a single event that made Parker realise that explaining the climate crisis was now part of the job. “Climate change is not causing hurricanes, but it is causing hurricanes to be more deadly and more destructive. It’s that incremental change that builds over time that has really sunk in for me – I now almost expect every storm to undergo rapid intensification.”

For Tobin, there were a few things that brought home the reality of the situation. First, the increased frequency of extreme weather events, such as record temperatures, rainfall, drought and wildfires. “It got to a point where it’s like: another record? We won’t do this one because we did a record the other day. It almost started to become boring, but the fact that there were so many records show something is going on.”

In 2017 there was another significant event for Tobin: she had a daughter. “I had already seen how things had changed between my mum’s generation and mine; now it was about how it was going to change for her. Having a daughter has definitely made me want to talk about it more. Before, it was: this could happen in so many years. Now it’s going to happen in her lifetime; it’s already happening. When you put a value and a feeling on that timescale it makes it more real.”

In 2021 Tobin went to Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic, to report for Good Morning Britain. She saw how the glaciers had receded, how the fjords were no longer freezing over, how this was affecting the wildlife: polar bears were dying, human economies were dying. And again there were tears, this time live on camera. “I didn’t mean to. I didn’t want it to be about me crying; I wanted it to be about the science. But I just saw the reality of it and it moved me. I realised that we – everybody – is responsible for that change. Seeing the reality compared to seeing and knowing the science was different. That was the moment for me when I was like: I want my daughter to come back and see this. If we don’t change there may be no reindeer, polar bears or glaciers when she’s my age. That was reality.”

Nasir experienced something similar reporting from Iceland for CBBC in 2013. “I interviewed the Icelandic mountain rescue team, and the way they described the glaciers it was almost like they were talking about their own extended families. They were so sad. They said: ‘Every year the glaciers are retreating. They’re dying. They are not going to grow back into the beasts they were.’ Those young people were seeing something in front of them, something that is part of what Iceland is all about, and I saw such passion but also such sadness and fear.”

Back then, Nasir says, the media thought it needed to provide a “balanced” point of view, and “even though the science at that point was pretty much spot on, they were allowing these climate deniers – whether they were in the pockets of the fossil fuel companies or whatever – to come on to voice their opinions without any factual backing whatsoever. I’m going to say this in the harshest possible terms: everybody had blood on their hands.”

Weather presenters have frequently come under fire from people with their heads buried in the heating sand. In 2020, Good Morning Britain did a piece about the bushfires in Australia. An Australian MP called Craig Kelly came on to say that climate change wasn’t responsible; Tobin had spoken to scientists and had the facts to show that it was. Afterwards, on social media, he called her an “ignorant pommy weather girl”. She hit back, listing her credentials: a degree in physics and meteorology, four years as an aviation forecaster with the RAF, 12 years as a broadcast meteorologist. She still uses #NotAWeatherGirl on social media posts.

For Parker in the US, it got nastier still. In 2016 the far-right website Breitbart News did a story saying the Earth was actually cooling, into which it embedded one of her Weather Channel videos, an unrelated piece about the La Niña phenomenon. The Weather Channel, and Parker, responded. “I defended climate science and there is pretty intense flak that you catch for doing that.”

Pretty intense flak included death threats. It was a dangerous time in her life, she says. “It is disgusting and disheartening, but unfortunately that has become a little bit the name of the game when you are talking about climate.”

Things may have changed a little since then, for the better. “I haven’t had many death threats recently,” she says with a wry smile.

Looking back, Rich remembers when the weather was the nice fluffy, smiley bit at the end of the news. “It still is to a certain extent,” he says. “The light to the shade of maybe a miserable news programme. I don’t mind but I think we have to think about that a lot harder these days.”

“You have to be very sensitive about the wording in your broadcast now,” says Nasir. “I’m criticised for not smiling very much when I present the weather. But for me weather is serious.”

Rich says it’s now about putting events into context, and using language that is appropriate. “So if it has been raining for three weeks and you then get a warm sunny day, we probably will say it’s going to be a beautiful warm sunny day. But if it’s been dry for months, the emphasis will be more: there is still no rain in the forecast. You flip it to more of a negative.”

Not so much “Scorchio!” then. It’s also about putting it into the even bigger picture. Rich says there’s a joke about weather people: “It’s the only job that you can go to work and get it wrong, then next day just go back and do it again – there is never any recourse.” But it doesn’t feel as though that is the case any more. “Things fit into a broader pattern that isn’t going away, and we do now have a role in education and communicating that.” You’ll still see him standing in front of a map predicting tomorrow’s weather, but he’ll also be the expert voice on news programmes and discussions, talking about climate. “For me it’s probably the most fulfilling part of the role.”

Parker agrees there’s now a responsibility to educate. “We have to communicate climate in almost every forecast because it is our responsibility to give people perspective.”

And to accusations of scaremongering? “It is scary!” says Tobin. “The reality of climate change is very scary. We had thousands more deaths across the UK, tens of thousands across Europe, because of the extreme heatwave. People were warned to take all the precautions they could, look after the very old and vulnerable. But the reality is that temperatures that are hotter than our bodies cause people to die, and that will become my daughter’s summer normal when she is my age. That is scary.”

No sugar coating from Tobin then, but nor does she want it to be all doom and gloom and it’s-too-late. Getting it on air helps; she has also written a book, Everyday Ways to Save Our Planet. “I want people to know this is bad but actually we can stop it getting worse.” She puts it another way, in forecast form, though one she might not get away with on breakfast TV. “The outlook is shit. But how shit is it going to be? You can be responsible for making it just a little bit shit, rather than like really, really shit.”

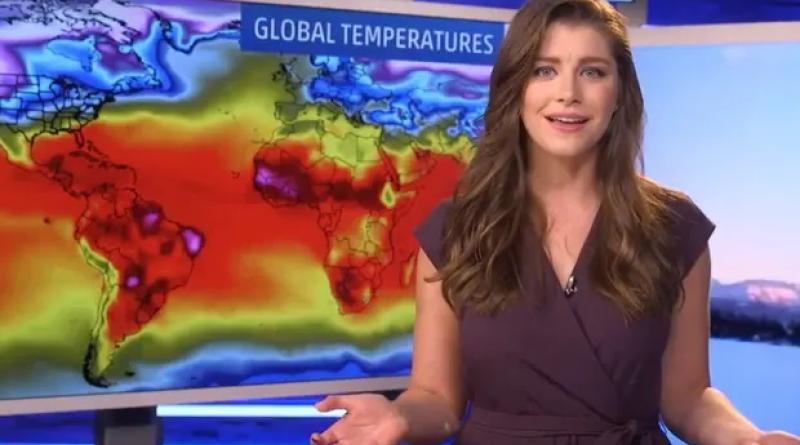

COVER PHOTO: ‘You constantly question: am I doing this well enough?’ … Kait Parker on the Weather Channel. Photograph: The Weather Channel