“If you make even relatively small adjustments in these fertility-rate trajectories, it accumulates, and suddenly a big country can have 100 million people more 80 years from now,” says Tomáš Sobotka, a population researcher at the Vienna Institute of Demography.

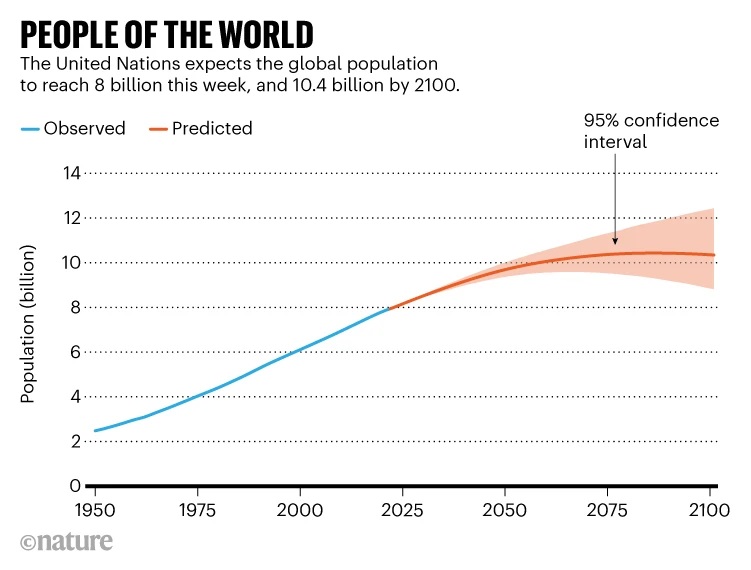

In 2018, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna forecast that the global population would be about 9.5 billion in 2100. The institute is now preparing an update, which will raise that estimate to between 10 billion and 10.1 billion. The change is due to higher observed and expected survival rates among children in lower-income countries, Sobotka says. Another factor is higher estimates of fertility rates in some large countries, including Pakistan.

More reliable data

The most significant factor behind the UN’s updated forecast is that data from China have been more reliable since the end of the country’s one-child policy in 2015.

“There was always a mismatch in the different sources of data coming from China during that policy,” Gerland says. Some parents, particularly if they had a girl, would not register an initial birth, he says. For that reason, many children did not appear in official statistics until they started to attend school. “We basically had to rely on education statistics for more accurate information,” he says.

The UN predictions suggest that China’s population has already peaked and will now shrink year-on-year until at least the end of the century.

“The Chinese statistics are suggesting there are already more deaths than births in China, and in that situation, the population will start to decline,” Gerland says.