At least $30 billion will be given to developing countries over the current decade to halt the decline in biodiversity. This was one of the major outcomes of the 15th United Nations Conference on Biodiversity (COP15), which ended on 19 December 2022 in Montreal, Canada.

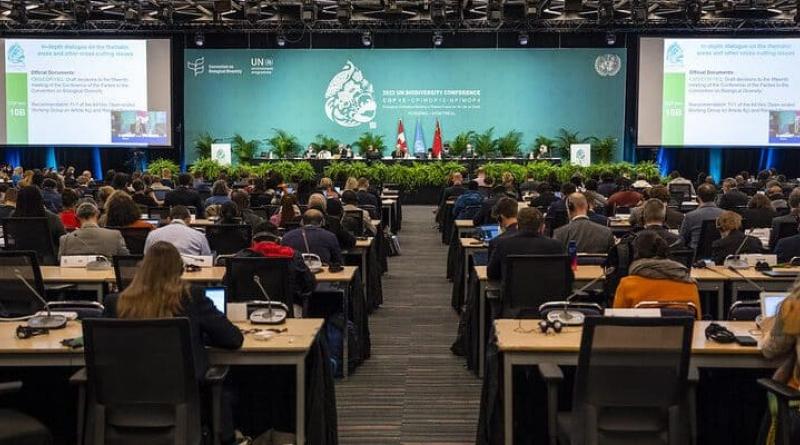

Paris won for the 15th United Nations Conference on Biodiversity (COP15). After four years of negotiations, ten days and one night of diplomatic marathon, the 195 countries plus the European Union (EU) reached an agreement under the aegis of China, president of COP15. This peace pact with nature, known as the “Kunming-Montreal agreement” (Kunming being the Chinese city where COP15 was initially to be held), aims in particular to protect 30% of the planet by 2030 and to release 30 billion dollars of annual conservation funding for developing countries.

This is the most important of the twenty measures contained in the agreement. It is also presented as the biodiversity equivalent of the Paris target to limit global warming to 1.5°C. The 30-30 target will be financed in stages, with a first stage of 20 billion by 2025, compared with just under 10 billion in 2022. However, this tripling of funding for biodiversity falls short of the 100 billion demanded by countries in the South, where biodiversity loss is accelerating due to human activity. “Most people say it’s better than we expected on both sides, for rich and developing countries. That’s the mark of a good text,” says Lee White, Gabon’s environment minister.

Guarantees for indigenous peoples

In addition to subsidies, developing countries were asking for the creation of a global fund dedicated to biodiversity, a matter of principle, similar to the one obtained in November to help them deal with climate damage. On this point, China is proposing as a compromise to establish a branch dedicated to biodiversity within the current Global Environment Facility (GEF) as early as 2023.

The text also provides guarantees for indigenous peoples, custodians of 80% of the Earth’s remaining biodiversity. It proposes to restore 30% of degraded ecosystems and to halve the risk of pesticides.

Read also-COP15: Southern countries demand $100bn per year to protect biodiversity

There are also shortcomings in the agreement. In particular, there are no figures for the preservation of endangered species, although these were included in the first versions of the text. Similarly, the explicit mention that the objectives were to be achieved “within the limits of the planet’s capacity”, which seems to be an element of good sense, was removed during the last negotiations. These flaws in COP15 will certainly be identified and addressed at COP16 on biodiversity, to be held in 2024 in Turkey.

Boris Ngounou