Biden’s Biggest Idea on Climate Change Is Remarkably Cheap

It’s one of the most cost-effective climate policies the U.S. has ever considered, according to a new analysis.

Over the past year, my climate reporting has had a few preoccupations. They include:

- Whether President Joe Biden will succeed in passing a major climate bill;

- The degree to which climate change is already a profound concern to the economy, and indeed whether the climate problem is more about “money” than “science”; and

- Carbon taxes.

Now, I have an occasion to bring all three together! A new analysis from researchers at the University of Chicago and the Rhodium Group, an energy-research firm, finds that one of President Joe Biden’s marquee energy proposals—the one of the most likely to make it through Congress—has a good chance of working.

Biden’s clean-energy tax credits—a set of incentives that would push the United States to generate more electricity through wind, solar, and other zero-carbon resources—would be one of the most cost-effective climate policies in American history, according to the analysis.

The researchers’ study, which has not been peer-reviewed, finds that the policy’s benefits will be three to four times larger than its costs, creating as much as projected $1.5 trillion in economic surplus while eliminating more than 5 billion tons of planet-warming carbon pollution through 2050.

“I will confess I was always a little skeptical of the tax incentives. I was concerned that they were expensive on a cost-per-ton-abated basis,” Michael Greenstone, a co-author of the study and the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor in Economics at the University of Chicago, told me. “I came away from this quite surprised at how beneficial this was.” (I should disclose that I worked with Greenstone last year when I was a journalist in residence at the University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute.)

“It’s very rare that we get opportunities to have policies with a benefit-to-cost ratio of 3 or 4 to 1. Normally it’s, like, 1.3 to 1, and we economists get very excited,” he said.

A year ago, I wrote that Biden’s infrastructure bill is the climate bill. Since then, that bill has been cut in two, renamed the Build Back Better Act, killed, resurrected, maybe killed again, and generally muddled over by Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia and the rest of the Senate Democratic caucus. Considerable controversy persists over what social-spending programs should go in the bill. But the climate and energy section has remained one of the most popular aspects of the bill—and one policy that has, so far, stayed within Manchin’s favor. “I think that the climate thing is one that we probably can come to agreement much easier than anything else,” he told reporters early last month.

As you may know, the United States already has a set of policies that could be described as “clean-energy tax credits,” a mishmash of tax breaks for solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal systems. But they are overly specific and kind of a mess, written at different times by different legislators. The tax credit for solar, for instance, gives developers a break whenever they invest in new solar capacity, while the wind tax credit gives them credit only when they produce a kilowatt-hour of wind power. They’re also designed in such a way that big banks end up capturing a lot of their economic value.

The new tax-credit scheme fixes those problems. The new tax credits are technology-neutral, allowing developers to use them when producing or investing in any kind of zero-carbon electricity (although they can’t claim both for the same project). And the new credits’ simpler design—they’re fully refundable—should eliminate banks’ overbearing role. The credits also include a few other tweaks that will make it easier for normal utilities, and not independent power producers that sell electricity to the highest bidder, to use them.

These tweaks make the tax credits much more efficient than other policies. At their peak, the incentives would eliminate 33 to 45 percent of carbon emissions from the country’s electricity sector, compared with a world without the policy, the analysis found. Because Biden’s strategy for decarbonizing the American economy depends on zeroing out carbon pollution from the electricity grid first, carbon savings in the electricity sector propagate through the system. The cleaner the grid, for instance, the cleaner electric vehicles become.

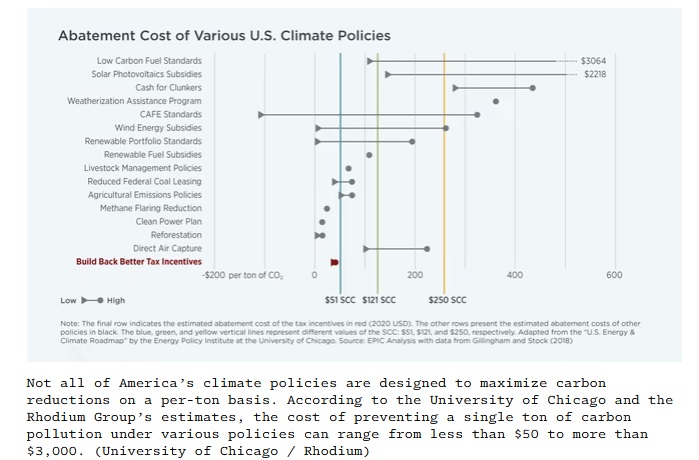

Under a conventional economic analysis, most of the government’s existing climate policies cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars to prevent a single ton of carbon from entering the atmosphere. The existing solar tax credits, for instance, can effectively cost up to $2,218 to abate a ton of carbon pollution. The new policies will cost the public only $33 to $50 to prevent a ton of climate pollution from entering the atmosphere, which is well below economists’ median estimate of how much each ton of carbon pollution costs the economy.

“Most of those other climate policies are just getting a small amount of tons,” Greenstone said. “But this is a quite broad policy that would give you a lot of tons.”

That’s in large part due to the huge collapse in the price of solar and wind, John Larsen, another co-author of the study and a partner at the Rhodium Group, told me. “Wind and solar are so cheap now and are projected to get even cheaper this decade. When you extend and enhance federal tax credits for a decade, it really leverages all this cheap tech in a way that just wasn’t possible five or 10 years ago.”

That places the clean-energy tax incentives at an unusual sweet spot: Although they’re normally explained as innovation policies, aimed at bringing down the cost of alternative and zero-carbon energy, they will also cheaply eliminate tons of carbon pollution. And because their per-ton cost is below the social cost of carbon, the tax credits may in some cases be more efficient than a carbon tax. Yet they seem unlikely to generate the political blowback that tends to greet a carbon tax.

“It’s cost effective, it gets a lot of tons, it gets at the sector that everyone says we have to get right the fastest—and we can do it without the tools everyone said we needed,” Larsen said. That sets a good precedent for the next time that Congress takes a look at the climate problem.

“Prior to 2021, the only way that people felt they could make big gains was with a comprehensive climate policy,” he said. “This shows that there’s a lot of ways to get points on the board with spending.”

In an email, Lynne Kiesling, an economist at the University of Colorado who was not involved in the study, agreed that the study found the tax credits may be cheaper than other policies. But she pointed out that the cost of paying for the policy isn’t the necessarily the same as its dollar-and-cents efficiency. “The cost of financing the tax credits is likely to be the variable of the most concern, both for the policy itself and for its broader macroeconomic tax consequences,” she said.

Remarkably, the study may actually underestimate the public benefit of the tax breaks, Larsen added, because he and his colleagues did not include an estimate of the money saved in medical bills from reducing conventional toxic air pollution. During the Obama administration, the benefits of reducing this conventional air pollution often paid for climate policy by itself. “Typically, the co-benefits of conventional pollutants are quite large—they’re usually of the same magnitude as the climate benefits,” he said. “It shouldn’t be dismissed.”

Society could reap the benefits of such a prosperous policy. But first, the bill has to pass.

cover photo: David Paul Morris / Bloomberg / Getty ]