COP26: Time to sober up

So how much progress has really been made in the opening days of COP26 and what are the main challenges that lie ahead?

To paraphrase COP26 president Alok Sharma, this is the moment when the rubber is finally meeting the road.

After a first week dominated by a blizzard of announcements of new initiatives in the real world, the conference is now moving into the critical, behind doors phase of the negotiations.

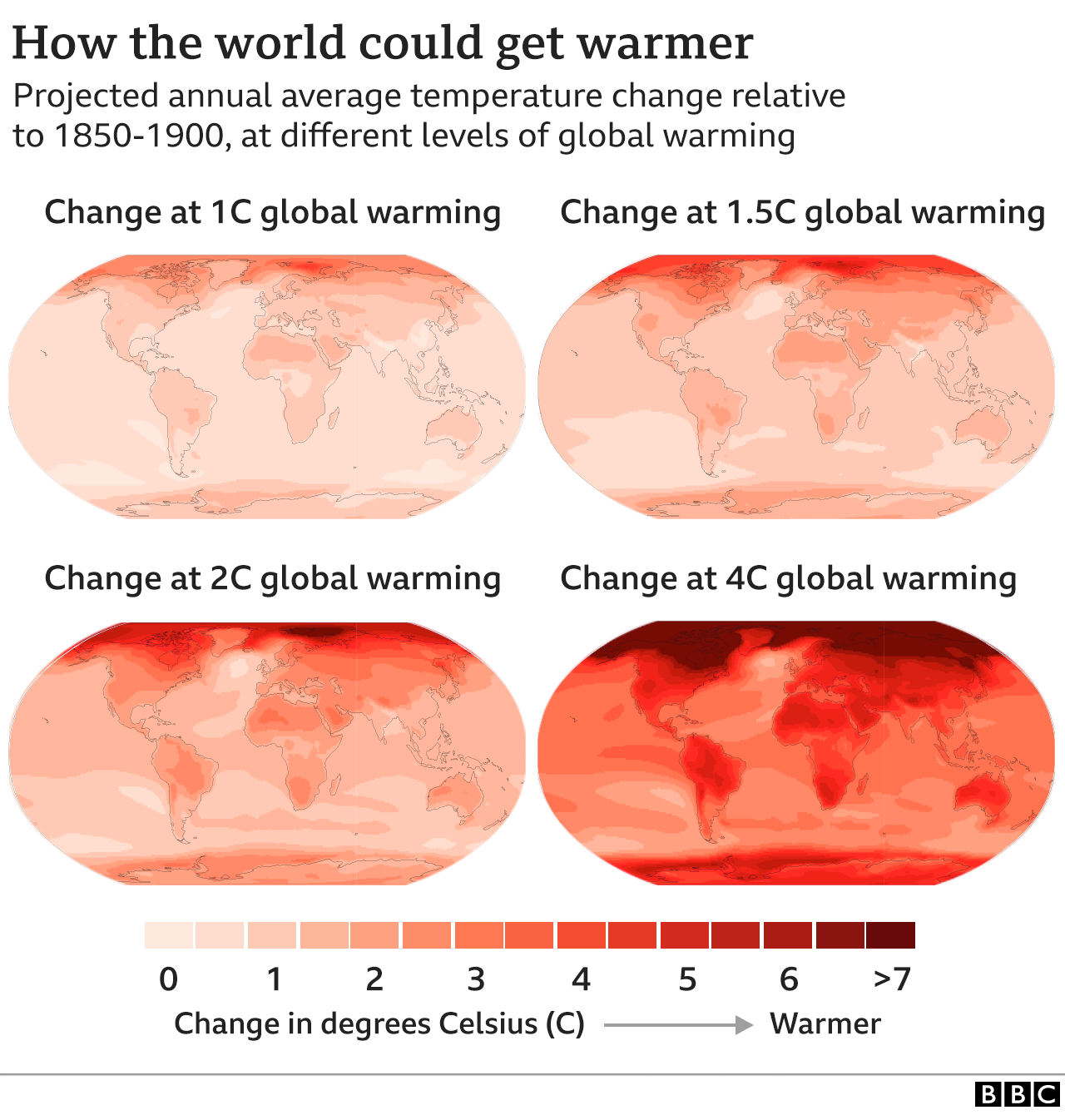

The main focus will still be on devising a plan to bend the temperature curve below 1.5C.

There has been quite a bit of speculation that the first week announcements made by countries and the new pledges on methane and coal have already moved the needle on the rise in global temperatures that's likely this century.

According to the head of the IEA, Fatih Birol, the new commitments mean that the mercury rise may be held to 1.8C.

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

At the start of the COP the latest analysis from the UN suggested a rise of 2.7C.

So just how real is this large predicted drop?

"None of the countries that has a net zero target has implemented sufficient short term policies to put itself on a trajectory towards net zero," said Dr Niklas Höhne, from the New Climate Institute, who monitor and assess national carbon cutting plans.

"Right now it's more a vision, or imagination. And it's not matched by action."

As one participant explained it, the first week of COP26 was all sugar rush, the second will be about sobering up and getting down to business.

Next week will see ministers fly in from around the world to tackle the tricky issues that negotiators themselves can't resolve.

These will encompass a range of technical issues relating to the Paris agreement that have been outstanding for a number of years, including the rules on how carbon markets work, on the need for transparent reporting, and for common time frames on emission cutting plans.

Some progress has been reported, but there are still wide gaps between the parties across these questions.

As deadlines loom, negotiators are getting nervous.

"It is tense right now, people are having to take tough decisions, as they should," said Archie Young, the UK's lead negotiator in the talks.

"I think it is really important that we recognise the hard work that goes into the importance of some of that technical work."

There will also be detailed and tough discussions around finance, around the question of adaptation, and loss and damage.

There is likely to be a real standoff over the question of how cash for climate change is spent.

Despite repeated calls from developing countries for a larger share of the finance to be used to help them to adapt to higher temperatures, the focus according to observers is still on using the money to help them cut emissions.

The cold reality is that investors are more willing to put their money into renewable energy projects where a profit can be made than they are to spend it on sea walls or other adaptive measures that do not guarantee a return.

"Rich countries publicly claim they care about adaptation but inside the talks most of the money goes on emission reductions and they undermine efforts to prioritise the adaptation needs of vulnerable nations," said Mohamed Adow, from the Power Shift Africa organisation, an observer at these talks.

The failure of the richer nations to fulfil their promise of $100bn by 2020 has undoubtedly damaged trust, there is work underway to put in place a new, more substantial payment from 2025.

While the new figure is unlikely to be agreed here, the prospect of a very significant increase could go some way towards ensuring that finance doesn't derail these talks completely.

For the UK though the really big question is how to construct a final document that will be agreed collectively by the conference that will keep the 1.5C temperature threshold within reach.

UK negotiators are taking soundings on what's termed a "cover decision", a package of measures that will try to close the gap between what the world's commitments add up to and the 1.5C bar.

The key element of that package will be an attempt to get countries to update and improve their carbon cutting plans more regularly than every five years as is presently the case.

The most vulnerable want an annual update. There's also a push for countries to come back with new plans in two years time.

There is likely to be strong opposition from larger, developing economies. But there is a belief that steps will be agreed.

"You clearly want some processes agreed here that give us hope that countries are going to come back and sharpen their pencils and put more ambition on the table," said Alden Meyer, a long time participant in climate talks from the E3G think tank.

"I think if we get the atmospherics, right and the UK uses the ministers well, by the end of next week, we can get substantial movement."

"It will offer some hope that over the next couple of years, we can start to really close that gap."

7 November 2021

BBC