Hydrogen: UK government sees future in low-carbon fuel – but what’s the reality?

The UK’s long-awaited hydrogen strategy has set out the government’s plans for “a world-leading hydrogen economy” that it says would generate £900 million (US$1.2 million) and create over 9,000 jobs by 2030, “potentially rising to 100,000 jobs and £13 billion by 2050”.

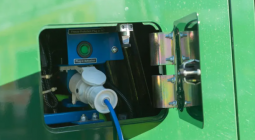

The strategy document argues that hydrogen could be used in place of fossil fuels in homes and industries which are currently responsible for significant CO₂ emissions, such as chemical manufacturing and heavy transport, which includes the delivery of goods by shipping, lorries and trains. The government also envisages that many of the new jobs producing and using “low-carbon hydrogen” will benefit “UK companies and workers across our industrial heartlands.”

On the face of it, this vision of a low-carbon future in some of the most difficult to decarbonise niches of the economy sounds like good news. But is it? And are there other options for delivering net zero that will be better for the public?

Let’s examine some of the claims.

A heated debate

The government prefers what it calls “a twin track approach”, meaning both blue and green hydrogen will be used to phase out fossil fuels. Blue hydrogen fuel is produced from natural gas – a fossil fuel which currently provides most of the UK’s water and space heating – but the CO₂ that would usually be emitted is captured and stored underground.

A recent report cast doubt on the green credentials of blue hydrogen, though. The research suggested that, because of methane emissions throughout the supply chain, blue hydrogen may actually be 20% worse for the climate than simply burning natural gas for heat and power. It doesn’t appear that the government’s strategy has recognised these issues or explained how they might be avoided.

Green hydrogen meanwhile is produced by splitting water molecules using electricity. A lot of energy is lost in this process, and so on average, the cost of hydrogen per kilowatt-hour (kWh) will be greater than the electricity it is derived from.

Is green hydrogen a better option for UK households than electrifying the heating system with heat pumps in homes? Green hydrogen bills are likely to be three to five times higher than this alternative. That’s because heat pumps take 1 kWh of electricity and convert it to around 3 kWh of heat, whereas green hydrogen takes 1 kWh of electricity and converts it to around 0.6 kWh of heat.

The strategy also proposes blending natural gas supplies to home central heating systems with 20% blue or green hydrogen. This, it’s reported, will help reduce CO₂ emissions from heating by 7%. No bad thing, but are there better ways to use that blue or green hydrogen?

Around 1 kg of hydrogen blended into the natural gas supplying a boiler could save 6 kg of CO₂. The UK currently produces around 700,000 tonnes of grey hydrogen a year, used to make fertiliser production and to remove sulphur from oil. This type of hydrogen is produced from natural gas too, but unlike blue hydrogen, the CO₂ emissions aren’t captured. For every kg of grey hydrogen produced, the resulting emissions are around 9kg. So roughly, grey hydrogen produces six million tonnes of CO₂ annually. Would it not be better for the UK to use that blue or green hydrogen to replace current grey hydrogen production than using it less effectively in blends with natural gas?

The strategy claims that hydrogen could be providing between 20% and 35% of the UK’s energy by 2050. That is at odds with the Climate Change Committee – a body of experts which advises the government on climate policy. In their most recent carbon budget, which projected UK progress towards net zero emissions in the 2030s, their main pathway forecast around 14% of total energy demand being satisfied by hydrogen by 2050.

By comparison, the EU’s modelled pathways for reaching net zero by 2050 range from zero hydrogen use to 23%, with the average around 12%. Even industry projections like Shell’s forecast only 2% hydrogen use by 2050. The upper range of the UK government’s projected hydrogen use in 2050 lacks credibility, in my opinion.

Then there are influential groups lobbying parliament on behalf of hydrogen, such as the Hydrogen Taskforce, which represents members with a vested interest in the fuel who are set to receive a significant amount of business from this strategy. But is what is good for business good for UK consumers and taxpayers?

The UK government has failed to provide comparative evidence that hydrogen is a preferred net-zero route in many applications. Only by comparing the paths to net zero in a way that considers the complete life cycle of hydrogen fuel, quantifying the impacts on people, profit and the environment can the case for hydrogen be made accurately. That evidence is lacking in this strategy.

August 2021

THE CONVERSATION