Climate crisis: Siberian heatwave led to new methane emissions, study says

Leak of potent greenhouse gas is currently small but further research is urgently needed, say scientists

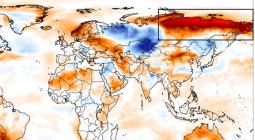

The Siberian heatwave of 2020 led to new methane emissions from the permafrost, according to research. Emissions of the potent greenhouse gas are currently small, the scientists said, but further research is urgently needed.

Analysis of satellite data indicated that fossil methane gas leaked from rock formations known to be large hydrocarbon reservoirs after the heatwave, which peaked at 6C above normal temperatures. Previous observations of leaks have been from permafrost soil or under shallow seas.

Most scientists think the risk of a “methane bomb” – a rapid eruption of huge volumes of methane causing cataclysmic global heating – is minimal in the coming years. There is little evidence of significantly rising methane emissions from the Arctic and no sign of such a bomb in periods that were even hotter than today over the last 130,000 years.

However, if the climate crisis worsens and temperatures continue to rise, large methane releases remain possibility in the long term and must be better understood, the scientists said.

Methane is 84 times more powerful in trapping heat than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period and has caused about 30% of global heating to date. Its concentration in the atmosphere is now at two and a half times pre-industrial levels and continuing to rise, but most of this has come from fossil fuel exploitation, cattle, rice paddies and waste dumps.

Prof Nikolaus Froitzheim, at Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn, Germany, and who led the Siberian research, said: “We observed a significant increase in methane concentration starting last summer. This remained over the winter, so there must have been a steady steady flow of methane from the ground.

“At the moment, these anomalies are not of a very big magnitude, but it shows there is something going on that was not observed before and the carbon stock [of fossil gas] is large.

“We don’t know how dangerous [methane releases] are, because we don’t know how fast the gas can be released. It’s very important to know more about it,” Froitzheim said. If, at some point in the future, large global temperature rises lead to a big volume being released, “this methane would be the difference between catastrophe and apocalypse.”

Methane releases have been considered a possible climate tipping point, in which emissions of the gas cause further warming, which in turn drives even more releases.

However, Prof Gavin Schmidt, at Columbia University in the US, who was involved in the study, said it did not make a methane bomb any more likely: “There is simply no evidence for a big feedback in [climate records going back 130,000 years], when we know that the Arctic was still warmer than today. If temperatures exceed those levels, there aren’t any historical analogues we can use, but we are still some way from those levels.”

The research, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used satellite data to examine the Taymyr Peninsula and its surroundings in northern Siberia, which was hit by the world’s most extreme heat wave of 2020.

The areas where methane emissions rose coincided very closely with the geological boundaries of limestone formations that are several hundred kilometres long and already exploited by gas drilling at the western end of the basin. Gas stored in fractures in the limestone would be trapped by a solid layer of permafrost. “We think that with this [heatwave], the surface became unstable, which released the methane,” Froitzheim said.

The study concluded with the suggestion that “permafrost thaw does not only release microbial methane from formerly frozen soils, but also, and potentially in much higher amounts, [fossil] methane from reservoirs below. As a result, the permafrost–methane feedback may be much more dangerous than suggested by studies accounting for microbial methane alone.”

Stéphane Germain, the CEO of GHGSat, the company that produced the satellite data, said: “We launched the Pulse tool in the hope that it would raise awareness and stimulate discussions. I am pleased that Prof Froitzheim and his team have been able to make use of it.”

As well as methane from thawing soils and fossil gas, there is a very large reservoir of methane frozen with water in some parts of the world’s oceans. However, scientists believe it will take a long time for global heating to warm up these deeper waters. Even if this happened, they expect much of the released methane to be dissolved into sea water and broken down into CO2 by ocean bacteria before it reaches the atmosphere.

2 August 2021

The Guardian