New Study Confirms Dangerous Sea Level Rise Projections Are Accurate.

A new study from Australian and Chinese researchers adds weight to scientists' warnings from recent United Nations reports about how sea levels are expected to rise dangerously in the coming decades because of human activity that's driving global heating.

The research, published Friday in the journal Nature Communications, found that sea level rise projections for this century "are on the money when tested against satellite and tide-gauge observations," as a statement from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) summarized.

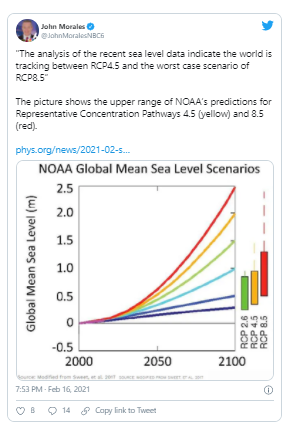

The researchers looked at projections from the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as well as the body's Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC), which include multiple representative concentration pathway (RCP) scenarios for how much humanity reins in greenhouse gas emissions.

Based on global and coastal sea level data from satellites and 177 tide-gauges, the researchers found that those two reports' projections under three different RCP scenarios "agree well with satellite and tide-gauge observations over the common period 2007–2018, within the 90% confidence level."

In other words, "our analysis implies that the models are close to observations and builds confidence in the current projections for the next several decades," said John Church, who is part of UNSW's Climate Change Research Center. The professor noted projections were accurate not only globally but also at the regional and local level.

However, because of the limited 11-year comparison period, Church added, "there remains a potential for larger sea level rises, particularly beyond 2100 for high emission scenarios. Therefore, it is urgent that we still try to meet the commitments of the Paris agreement by significantly reducing emissions."

The Paris climate agreement aims to limit global temperature rise this century to "well below" 2°C—preferably to 1.5°C—compared to pre-industrial levels. Study after study has shown that current emissions pledges aren't adequate to even meet the higher target. The U.N. reports' three studied pathways are RCP2.6, RCP4.5, and RCP8.5, with the first being the closest to the less ambitious Paris goal and the last being the most dire.

"The analysis of the recent sea level data indicate the world is tracking between RCP4.5 and the worst case scenario of RCP8.5," Church warned. "If we continue with large ongoing emissions as we are at present, we will commit the world to meters of sea level rise over coming centuries."

The release of the SROCC in September 2019—with its warnings about the dramatic impact that global heating will soon have on humanity, marine ecosystems, and the global environment—sparked a flood of demands for bolder climate policy.

As Food & Water Action executive director Wenonah Hauter said at the time, "This report tells us that due to decades of foolish reliance on fossil fuels and resulting climate warming, our oceans are on life support, which means we are all now on life support."

"We must treat this alarming science as a final warning: In order to avoid a fate of extreme global climate chaos and mass death at the hands of our poisoned oceans, we must act swiftly and aggressively to turn the tide now," Hauter added. "We have been given a final warning. There can be no more excuses."

The IPCC's SROCC found that global sea level could rise by 30-60 centimeters, or about 1-2 feet, by 2100—and a rise of 110 centimeters, over 3.5 feet, was possible but unlikely. However, researchers from the University of Copenhagen's Niels Bohr Institute recently found that under the worst case scenario, the world could see a rise of 135 centimeters, or about 4.4 feet, by the century's end.

"The models we are basing our predictions of sea level rise on presently are not sensitive enough," said Aslak Grinsted, associate professor at the institute. "To put it plainly, they don't hit the mark when we compare them to the rate of sea level rise we see when comparing future scenarios with observations going back in time."

The institute's research, published earlier this month in the journal Ocean Science, introduces a new method of quantifying how the sea reacts to warming, which involves analysis of historical data.

"You could say," Grinsted added, "that this article has two main messages: The scenarios we see before us now regarding sea level rise are too conservative—the sea looks, using our method, to rise more than what is believed using the present method. The other message is that research in this area can benefit from using our method to constrain sea level models in the scenarios in the future."

In a Twitter thread on Sunday, Grinsted detailed how the new study in Nature Communications "zooms in at 2007-2018 and finds no significant disagreement" with the research his team released, which found "a substantial discrepancy between the sensitivity of sea level models and observations."

"Both studies would have been able to make more solid conclusions if the IPCC had published hindcasts," Grinsted said at the end of the thread. "I hope that upcoming IPCC will take this to heart and publish hindcasts (e.g. 1850-now)."

17 February 2021

EcoWatch