Polar Vortex: Everything You Need to Know.

Let's not waste time. You will need: warm clothes, plenty of firewood and enough supplies (flour, yeast, toilet paper — the usual) to not have to leave the house for the next week or two.

No, just kidding. For pandemic control, it would be helpful if we all stayed home, but as a precautionary measure against the approaching polar vortex, this would really be over the top. It's probably indeed going to be bitterly cold in much of the Northern Hemisphere, but we're not in for an apocalyptic winter scenario.

In the past few years, especially during the cold North American winter of 2013-2014, the term "polar vortex" has been increasingly used in people's weather vocabulary and blamed — sometimes rightly, sometimes wrongly — for any outbreak of wintry weather or very cold temperatures. So, for example, the unusual extreme snowfalls in Spain could have had something to do with the phenomenon. Key word here is could.

The polar vortex was first described in 1853 and first observed by radiosondes during the winter in the Northern Hemisphere in 1952.

However, when we use phrases like "The polar vortex is coming" or "The polar vortex is here," we probably break the icy heart of every meteorologist. The polar vortex does not come and go — it is often present in our atmosphere during winter and spins around the hemispheres like a stormy roundabout, so to speak.

That actually means: There is not one vortex, but two — one at the North Pole and one at the South Pole. Their dynamics and potential are expressed with the help of the Arctic Oscillation and Antarctic Oscillation Index. To keep it short: AO and AAO.

What Exactly Is a Polar Vortex?

The Arctic polar vortex is a circulation of wind high up in the atmosphere — a very ordinary phenomenon, in other words. It forms every year in autumn, when the sun barely reaches the North Pole. In spring, it slowly dissipates again.

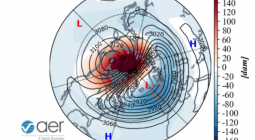

The air up there is extremely cold in winter. The polar vortex can strengthen and weaken. Wind speeds exceeding 320 kilometers per hour (200 miles per hour) are typical at an altitude of 10 to 50 kilometers (6 to 30 miles) in the stratosphere, where it is sometimes well below minus 70 degrees Celsius (minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit). This is directly above the troposphere, the part where weather occurs.

The polar vortex thus has no direct effect on our weather, but there are still interactions: It influences the jet stream. This band of high velocity wind blows at an altitude of 10 kilometers (6 miles) and controls the high- and low-pressure systems.

In a typical winter, the jet stream is quite strong and brings mild windy and rainy weather from the Atlantic to Europe. The polar air stays in the vortex. However, if the jet stream is weak, there are bumps in the jet stream, and a polar vortex split could happen.

The Collapse: Will It Become Frosty Now?

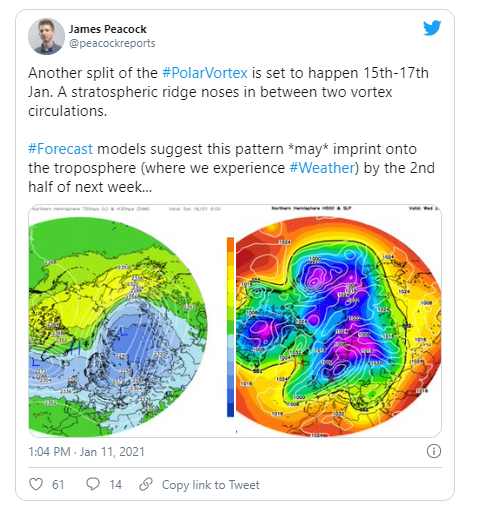

Every now and then, about every two winters, there is a strong warming of the stratosphere due to warmer air flowing in. Greenland and the North Atlantic, for example, are said to throw the vortex particularly out of balance with their warmth.

The polar vortex stumbles — or rather squiggles — and air currents can assert themselves more frequently. This split causes temperatures in the stratosphere to rise by 60 to 80 degrees Celsius within a very short time.

To put it more graphically, you can imagine a flying circle of pizza dough that is jerking through the air out of shape. In the worst case, the pizza (the vortex!) loses its shape completely or even splits.

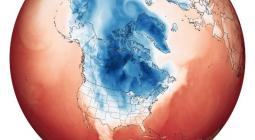

Then there is a lot of whirling up there, which also has an effect on the entire Northern Hemisphere: Arctic air provides for icy temperatures.

This is exactly what happened on January 5, 2021, and will probably hit us again soon. Forecasters say we can expect the cold snap in mid to late January, and it could last in spurts into February. Again, key word: could.

Or Maybe Not ...

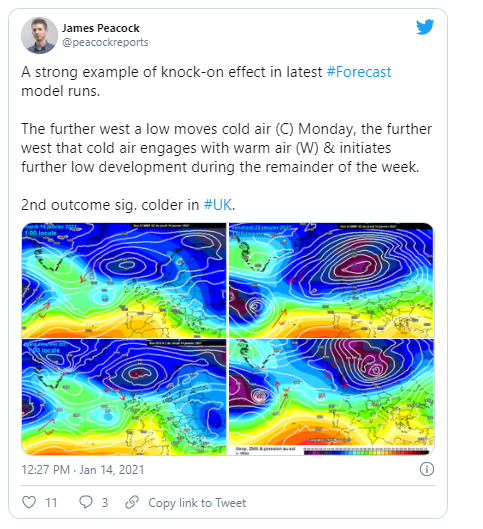

But the phenomenon of the interaction between the polar vortex and wind circulation is complicated — and not yet fully understood. Meteorologists disagree on whether there really will be a freezing winter onset.

The reason: the approaching Atlantic depressions. They are supposed to cause the winter air to move from the west further to Russia, and the snow line is supposed to rise to over 1,000 meters. But that does not mean that it will stay that way for the rest of winter. The cold may well return.

In the end, the weather just does what it wants — whatever our forecasts.

8 February 2021

EcoWatch