Why the coal sector is so excited about Australia's move to 'clean' hydrogen.

Key points:

- Australia's national hydrogen strategy is due for completion by the end of the year

- Hydrogen can be made using fossil fuels or renewables but it will be cheaper to use coal and gas for at least a decade

- Japan's demand has been inflated in official government materials, overstating the short-term export potential

Japan might be endowed with many beautiful things but reliable and cheap sources of energy are not among them.

Home to 125 million people and one of the world's worst nuclear meltdowns, the allure of hydrogen energy has driven Japan's ambition to become a leading adopter of the energy source.

Next year's Tokyo Olympics will serve as a demonstration of the country's progress towards a so-called hydrogen society, based on carbon-free, next-generation technology.

It is keen for cars that produce exhaust — water — that technically could be drunk. The Olympics itself will be home to buses like this:

And key to its strategy for this clean-energy future is something that may surprise — Australia's brown coal.

Japan's strategic hydrogen roadmap, released earlier this year, states plainly that 2020 targets are set "assuming the success of Japan-Australia brown coal-to-hydrogen project".

That project, a trial using coal from Latrobe Valley in Victoria, will demonstrate how Australia's hydrogen export industry — and Japan's imports — might work.

But its prominence also hints at a tension threatening to tear the Australian hydrogen movement apart.

The recipe for hydrogen

Hydrogen is attractive as a fuel source because it carries more energy than natural gas and is carbon-free, so the burning of it does not contribute to climate change.

It can be produced by the process of electrolysis of water using large amounts of energy — think solar and wind-sourced — or chemical processes associated with combusting fossil fuels like coal and gas.

That sets up an ideological split between fossil fuels and renewables.

While the hydrogen itself emits no carbon when used, the cheapest way to produce it right now does.

Those preparing Australia's hydrogen strategy recognise the need to reduce emissions to combat climate change, and are only considering options using fossil fuels if they come with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The most prominent examples of CCS involve pumping carbon emissions into underground cavities, but critics argue the technology is unproven and ineffective.

Mark McCallum at Coal21, a group representing black coal producers pursuing CCS, wrote in a submission to this year's hydrogen strategy consultation that the technology was proven, citing the example of the Norway's Sleipner 20-year-old project.

"Importantly, CO2 [carbon dioxide] is a stable substance and, provided the well-established industrial safety protocols are followed, the injection process can be conducted without any threats to the health and safety of workers or the public."

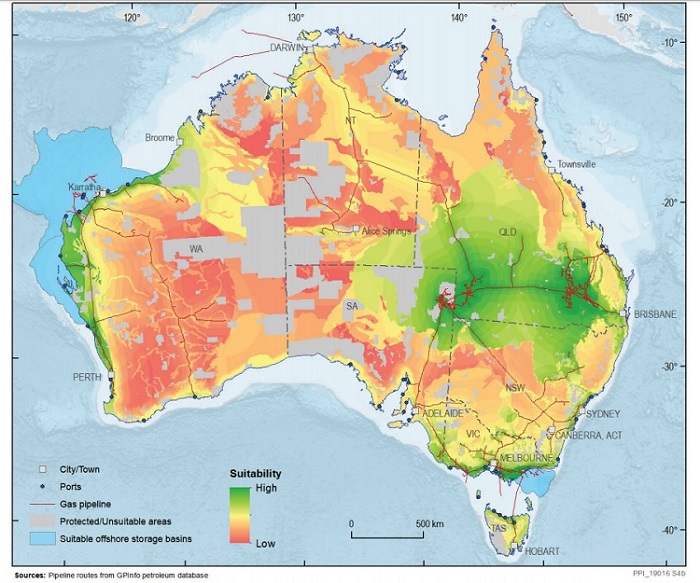

Suitable locations for hydrogen production, factoring in proximity to geology suitable for storing emissions, have already been identified by Geoscience Australia:

There may be issues with leakage from the emissions, or cost blowouts with rolling out the technology at a large scale.

But assuming there's not, it will be much cheaper to produce hydrogen using fossil fuels over the next few years.

However, the renewables-driven alternative is already better for the climate, and at some point after 2030 its price is also likely to be cheaper.

The 'inflated' prize of Japan

The briefing paper for COAG energy ministers notes "access to the Japanese energy market is the prize for the nations now bidding to be global hydrogen suppliers".

But it is not clear exactly how big that prize is.

Much of the hype around hydrogen in Australia focuses on the export opportunities.

The thinking goes that Australia could use its natural endowment in coal, gas, sun and wind and supply the world with hydrogen, starting with Japan.

This future, according to some, is just around the corner.

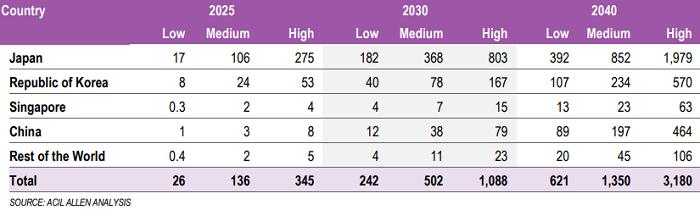

The first issues paper for the National Hydrogen Strategy trumpets: "High-level economic modelling by ACIL Allen estimates that hydrogen exports could provide around $4 billion direct and indirect economic benefits to Australia by 2040 under medium demand growth settings."

Under those "growth settings", consultants ACIL Allen estimate that Japan will need 1.76 million tonnes of hydrogen per year in 2030. It suggests Australia could provide 368,000 of those tonnes.

If ACIL's estimates are correct, more than 2,000 Australian workers will benefit from the burgeoning industry in the next decade.

However, Japan's own strategy projects its own demand in 2030 at just 300,000 tonnes. That's less than one fifth ACIL's estimate of Japan's consumption.

Anthony Kosturjak, a senior research economist at Adelaide University, said the ACIL estimate "does seem optimistic".

"The low-export scenario of 182,000 tonnes is more reasonable as this would represent about 60 per cent of the national target," he said.

Mr Kosturjak, who researched 19 national hydrogen plans this year for a research paper funded by the Department of Industry, warned that Japan's targets were aspirational but also competition was intense, noting Japan had set up projects in other countries, including Brunei and Norway.

"It is important to remember that the Japanese strategy identifies an aspirational target and there is significant uncertainty regarding how the technical and economic feasibility of hydrogen and competing technologies will evolve," he said.

"As such, the country could significantly overshoot or undershoot its target."

According to ACIL's estimates, Japan will provide the majority of world demand in 2030.

How a boom changes the strategy

John Soderbaum, director of science and technology at ACIL Allen, said the scenarios in the report "are not forecasts of hydrogen demand by any particular country, rather they are projections of the potential overseas demand for hydrogen under three different scenarios".

"We then explored what it would mean for Australia in terms of export revenues and employment if that projected overseas demand for hydrogen imports was met in part by Australian exports."

However Richie Merzian, the director of the climate and energy program at left-wing think tank The Australia Institute, described the numbers as "inflated" and argued they were being used to justify fast-tracking the hydrogen export market.

"Public money is being channelled into developing coal and natural gas-based hydrogen plants," he said.

31 October 2019

ABC NEWS