Is toxic masculinity the reason there are so many climate-hesitant men?

With Cop26 coming to an end and the climate crisis more prevalent than ever, why are some men still so hesitant to change their everyday habits to save the environment? Kate Ng investigates

The climate crisis has been at the top of nearly every political and social agenda this past fortnight, with the eyes of the world on the United Nations Climate Change Conference (Cop26) that has been taking place in Glasgow. But, as world leaders hammered out commitments, promises and agreements to tackle the urgent issue of global heating, attention has turned towards what behavioural changes the general public can adapt to help the environment.

The UK’s chief scientific advisor, Sir Patrick Vallance, stressed the importance of behavioural changes as part of climate action while at the summit. He said that, while most of us assume making greener choices means dramatic changes to our everyday habits, most of these changes are easier than we think. “I think [behavioural change] is starting. Is it where it needs to be yet? Probably not and I think there’s more to go,” Vallance explained. “But I think there’s a willingness and an engagement taking place that is going to be important.”

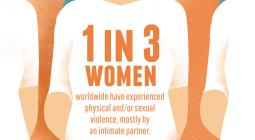

A new study has found that around half of the world’s population needs to do more to tackle the climate crisis. It said that men, in particular, need to be more willing to change their habits to become more eco-friendly compared to women. The report by think tank Global Future also found that significantly more women experience high levels of eco-anxiety compared to men, with 45 per cent of women reporting feeling anxious about the climate crisis compared to 36 per cent of men.

Male and female spending habits also show a divide in our response to global heating. Global Future’s report, titled “A Crisis in Common”, found that some 40 per cent of female respondents say they have changed the way they buy and eat food in order to help fight climate change. In contrast, just 27 per cent of male respondents reported doing the same. The figures are similar when it comes to buying clothes, with almost 34 per cent of female respondents saying they have changed their habits compared to 16 per cent of male respondents. But what is behind men’s reluctance to alter their everyday habits in order to become part of climate action? And more importantly, what can be done to encourage them to be more proactive in climate justice?

The solution has to be a nuanced one, and is not as simple as putting the blame squarely on the shoulders of men. In fact, experts say that would be counterproductive. Katrien Van der Heyden, a gender expert specialising in masculinity and climate change, says men who stick to the “traditional” definition of masculinity are more likely to be disinclined to act for the planet. She explains: “The problem is not with men as such. We have many male allies who are willing to do their part. Instead, the root cause is in patriarchal masculinity, and there are many names for this, including toxic masculinity. It is the traditional way of defining masculinity as everything that is not feminine and everything that is power and privilege that holds many men back.”

According to Van der Heyden, men who subscribe to this idea of masculinity often believe that being caring equates to being feminine - and that “real men” are anything but. “This subset of men believe the role of the man is to gather wealth and richness, to make economies grow but in the worst possible sense,” she says. “In many cultures, this kind of masculinity is still widely promoted among boys. We see that men who follow this recipe are much less inclined to take care of the climate and do their part to heal the Earth. That’s a huge problem because there are still many men and boys who get that message, and that’s where we need to change things.”

However, John Barry, a psychologist and managing partner at the Centre for Male Psychology, warns that framing the reluctance of some men to take part in climate action as “toxic masculinity” could lead to them “switching off” from the conversation. “If you go around trying to shame men into doing something, that’s not what works, especially if they think that this is not really a strong reason for doing something,” he tells The Independent. Instead, Barry says that men tend to lean towards actions that provide instantly tangible results, which could be why taking what are perceived as small actions - such as recycling or choosing more sustainable clothing brands - puts many men off doing it.

He says that the case for the climate emergency has not been made “sufficiently strong”, otherwise “everybody would be sold”. This is echoed in the results of a poll carried out by Kantar Public, which found that, although the majority of people - both men and women - are alarmed by the climate crisis, few are willing to make significant lifestyle changes. The survey of 10 countries, including the US, UK, France and Germany, found that 62 per cent of people saw the crisis as the main environmental challenge faced by humanity, but almost half 46 per cent believed there was no real need for them to change their personal habits.

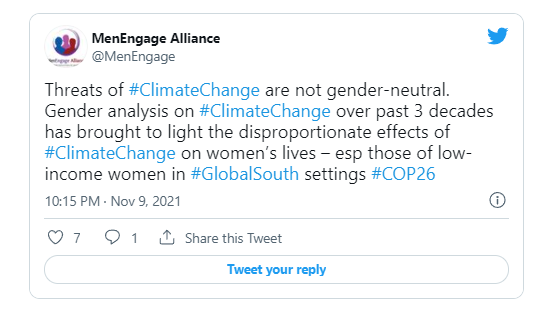

Yet, there is still a pressing need for climate leaders and organisations to engage men in taking action to save the environment. A discussion paper by the MenEngage Alliance, a global network that works to involve men in “achieving gender justice”, reveals how gender identities affect men and women’s “roles, activities and subsequent contributions to carbon emissions”. It suggests that young boys being taught to be “assertive, unfeeling and unafraid” could be why men perceive the climate crisis to be less of a threat than women do. “Patriarchy is harmful to our climate,” the authors write. “Efforts are needed to advance this perspective by engaging men as human beings who are also vulnerable to disasters brought on by climate change and as actors with agency to enact change alongside women activist allies.”

Van der Heyden says more initiatives like MenEngage - with whom she is an independent consultant - are necessary to drive conversations and find solutions on how to involve more men in climate action. She says men who wish to take action on the climate crisis often don’t have a role model so don’t understand what they can do to care for the planet. She adds: “Once they start to talk about this and explore different ways of being a man and being human, then they can start to look at climate change in a new way.”

November 2021

INDEPENDENT