Tourism is sucking Utah dry. Now it faces a choice - growth or survival?

Booming expansion to meet the demands of thousands of visitors every year is squeezing dwindling water supply

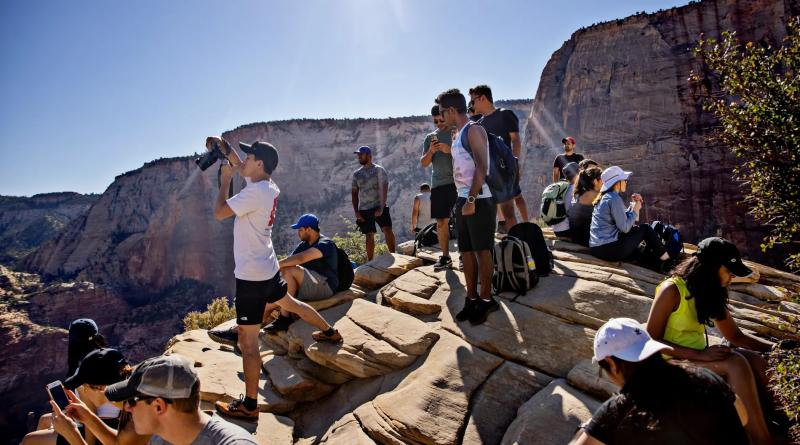

It was a typically hot summer day in Utah’s Zion national park, where early-afternoon heat hovered near 100F, even in the shadows of the red peaks soaring overhead. But the extreme conditions did little to dissuade the throngs of tourists who trudged into the chalky brown waters of the Virgin River.

The parking lot at Zion – one of the United States’s busiest national parks – had been full since 8am. Many of the visitors were there to scramble into the shallows of the Virgin River for the ever-popular and Instagrammable Narrows hike.

Thousands of tourists descend on this waterway year after year, even as this region and others across the American west fall deeper into drought. Fueled by the climate crisis and the overuse of dwindling water resources, the drought threatens the safety and sustainability of the spectacular sights; at the same time, tourists and the industries that cater to them contribute to an unfolding crisis in the cherished lands that brought them there.

“The point is not just how out of touch tourists are when they come and visit,” says Martha Ham, an environmental advocate with non-profit Conserve Southwest Utah, noting the lush lawns in surrounding residential developments. “We are not facing [the fact] that we live in a desert or dealing with what our natural limits are,” she said. “It is a historic problem and it catches up with you. It is catching up with us here.”

Just beyond the park, the once-sleepy city of St George is rapidly expanding. Tucked into one of the hottest and driest cornersof south-west Utah, the gateway community is the fastest growing city in the US. Tourism has driven new residential growth and businesses in an area that could soon see water shortages – and it’s only expected to get worse.

Though there have been recent moves to try to curb consumption, Utah already has the highest per-capita water usage in the country. In Washington county – home to Zion and St George – usage was an alarming 285 gallons a person a day in 2020, more than double what those in Las Vegas, just hours to the south, use.

“We have had that infamous distinction for three decades,” said Zachary Frankel, executive director of the non-profit Utah Rivers Council, noting that water managers have also kept water rates exceedingly low, so that residents and businesses in Utah also have the cheapest water in the country – which doesn’t help slow demand.

“There’s a cowboy-level of understanding of water that is not very sophisticated – and not very sustainable,” Frankel added.

While western states grapple over how to ration the rapidly declining water resources and how to secure a future in which the climate crisis is driving aridification and severe storms in this part of Utah, the churn of new construction hasn’t slowed. As new houses and resorts march deeper into the desert, officials are searching for new sources of water as it grows more scarce in the drought-stricken American west.

“Our city officials are trapped because they borrowed money, they made plans for growth – they are in a hell of a bind,” Ham said. “There are also economic consequences in the battle charge of, ‘We have to save our economy.’”

Rampant growth may come at the highest price, she added. “It’s a boomerang.”

Stopped under a strip of shade, the Fullmer family looked back on the four miles of gurgling waterway they’d travelled hours from Las Vegas to trek through. Heath Fullmer said he hadn’t visited Zion for 15 years but the landscapes still felt familiar. What had changed, he said, was the surrounding community.

“The area in town is really different,” he said, adding that the tourist hub was smaller and quieter in his memory. “It used to be less commercial.”

New resorts have sprouted across Utah over the last decade, and their lush lawns and water-intensive amenities now dot the desert landscapes. It didn’t happen accidentally. Utah has worked hard to promote the state as a top-notch destination. In St George alone, the tourism board has invested roughly $25m over the last 10 years to improve local amenities. There are 13 golf courses in just a 20-mile radius near Zion, which has drawn visitors and new residents.

Zion itself saw a nearly 50% jump in visitation between 2014 and 2019, according to an analysis by the University of Utah. About 1.7 million more visitors went to the park in that five-year span, and they brought their wallets with them. In 2019 alone, Zion visitors dropped an estimated $1,133 a stay and contributed a record $434m to local economies, according to the analysis.

But while that boosted the bottom line in communities like St George, it had a negative impact on Zion’s “visitor experience, local gateway communities, and the natural environment”, the University of Utah researchers wrote. The very thing driving its growth is now threatening its survival. The delicate desert ecosystems and low-income locals will be the first to pay the price when water runs out. As the climate grows more extreme, visitors are also facing new and increasing dangers.

“Utah is right in the bullseye of the US’s climate change impacts,” said Jon Meyer, assistant state climatologist at the Utah Climate Center, noting the “buffet of climate impacts” across the state. From declining snowfall in the winter and summer heatwaves to drought and destructive deluges, the conditions have been “an inflection point that has driven home the idea that Utah, its citizens and its economy are very impacted by the idea of a changing climate”, he said. “People are finding themselves in riskier situations for more days of the year.”

As visitation in Zion surges – the park surpassed 5 million visitors for the first time in 2021 – search and rescue operations are also on the rise. During the busy season, there are sometimes several emergency medical incidents in a single day.

Popular attractions like the Narrows hike can turn dangerous – or deadly – very quickly, and getting visitors to understand the risks can be a challenge. In a single season, this waterway was affected by toxic algal blooms that can occur when water levels wane and warm, and surging flash floods that can end in tragedy. One woman died in a flood last month.

But with the sun shining brightly and clouds collecting against the horizon, few visitors seemed concerned. Ian Gonzalez, who said he had wanted to visit the Narrows for years, admitted that he and his group, which included a baby in a backpack carrier and a young child, “were just blithely going at this without looking at the conditions”. He said, with a smile, that he wasn’t worried.

Others were more prepared, equipped with gear, and had a better sense of the risks lurking around the riverbend. Kassidy Burns, who had traveled from Colorado to see the sights, had closely followed weather reports. “We had heard they had rainstorms and that someone got washed out and passed away,” she said.

But there’s another hazard in this river system that may be less apparent to people just passing through: the levels of the waterway are declining.

“The Virgin River is going dry,” said Robin Silver, a co-founder of the Center for Biological Diversity. Calling the river a canary in the coal mine for the water woes across the west, he added that much of the problem stems from how “the city of St George is growing in an unsustainable way”.

Tourism has only added to Utah’s image as the place to call home. With new attractions taking root to cater to visitors, researchers at the University of Utah found that tourism advertising helps cast the state as a “place where people want to live, work, buy a second home, retire, start a business, start a career, or go to college”, driving residency along with visitation.

Along with millions of tourists, retirees and remote workers have descended on this region recently, lured by stunning views and opportunities for recreation. Washington county officials are preparing for the population to more than double in the next three decades from its present population of just 180,000, just as water supplies across the region wane.

“People come here and they never want to leave,” says Ed Andrechak, vice-president and water program manager for Conserve Southwest Utah. He knows from experience. During a family trip to the area in 2017, he found himself meeting with a realtor. It didn’t take long before the retired environmental engineer called Washington county home. But Andrechak is also worried about the region’s precarious future. He started volunteering for the organization after learning what was at stake, offering his expertise in an attempt to build a culture of conservation strong enough to permeate public policy and the sightseer subconscious.

“We are so disconnected from the land or the water that we don’t even think about it,” Andrechak says, adding that the answer doesn’t lie in inventions or dramatic new water supply diversions, but in becoming more water-wise. “We can save ourselves by ourselves. I believe that analytically as an engineer and I believe it spiritually as a resident.”

But rather than curbing growth, requiring residents to rip up their lawns, or limiting allotments to already established resorts, golf courses, and other attractions, Utah is searching for new supply in an increasingly water-scarce region.

State lawmakers and water managers have pushed for a controversial pipeline that would pump water from the beleaguered Lake Powell reservoir across the desert and into St George for decades. States that rely on the rapidly declining Colorado River, which feeds into that reservoir, have resisted the plan, saying shortages in the system are already being felt.

There is also a push to drill deep for water, tapping underground aquifers, that could lead to irreversible effects. “The water in the ground has taken many millennia to accumulate,” Frankel said. “So when we just drill a new well and suck the aquifer dry without thinking about how much water is there, we are not planning – we are just haphazardly proceeding. That is what we are seeing throughout this south-west corner.”

But there’s still a lot that can be done to spur conservation. Martha Ham has hope that this period of intensity will inspire collaboration and help launch a new culture around protecting the beloved – and essential – riparian resources.

“It is getting loved to death,” she said, noting the need to help tourists and locals connect more deeply to the waterways and landscapes. Time for change is running short. Without a shift, the desert ecosystems will be imperiled along with the industries and communities that have come to rely on them.

“Regardless of where you live in the world, it is crucial to be in touch with the natural limits of your environment,” she said. “People who think of visiting Utah, I hope when they come they see more evidence of us being in touch with our natural limits.” Otherwise, she added, “we will all just be floating over a waterfall”.

-

This is the first of seven stories in our coverage of the megadrought. Our second story, out tomorrow, delves into the origin of this catastrophe.

by Gabrielle Canon with photographs by Kim Raff