Tears at bedtime: are children's books on environment causing climate anxiety?

Greta Thunberg-effect behind sales boom in books on everything from plastic waste to endangered wildlife

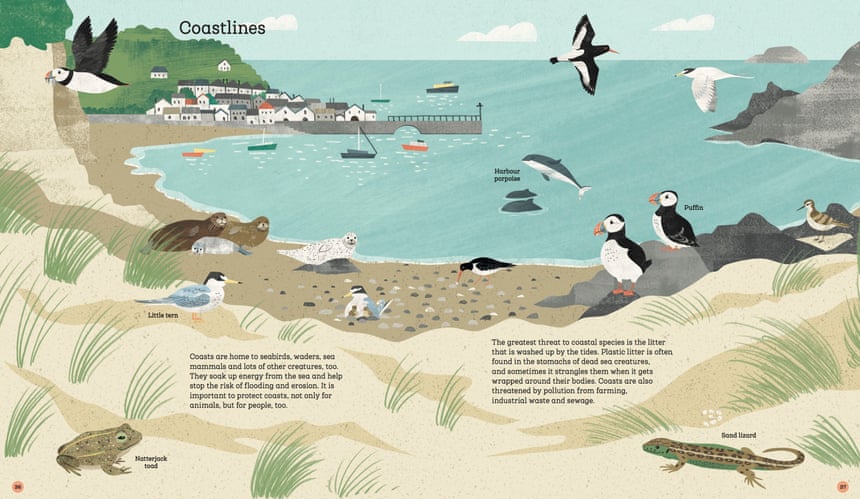

I ’m reading one of a small forest’s-worth of beautiful new picture books about the environment with my eight-year-old twins. The Sea, by Miranda Krestovnikoff and Jill Calder, takes us into mangrove swamps and kelp forests and coral reefs. We learn about goblin sharks and vampire squids and a poisonous creature called a nudibranch. Then we reach the final chapter on ocean plastics. When we learn that by 2050 there could be more plastic in the ocean than fish, Esme bursts into inconsolable tears.

Since the deserved success of The Lost Words, a large book filled with beautiful paintings of everyday wildlife by Jackie Morris and “spells” by Robert Macfarlane, which my children loved chanting aloud, bookshops have been filled with other gorgeously illustrated oversized tomes about nature and the environment. There’s Ben Hoare’s gilt-edged Anthology of Intriguing Animals, A Wild Child’s Guide to Endangered Animals by Millie Marotta, and other recent classics such as the lovely How Does My Garden Grow by Dutch author Gerda Muller and A First Book of Nature by Nicola Davies.

Consumers are spending more money than ever on books for children, and the number of new children’s books about the climate crisis and wildlife has more than doubled over the past year, with sales also doubling, according to data from Nielsen Book Research.

The Greta Thunberg effect is creating a new library of children’s books about eco-warriors. Nosy Crow rushed out Earth Heroes four months after signing up author Lily Dyu, selling 9,000 copies in the UK since publication in October. Macfarlane and Morris have just announced a Lost Words sequel, which will be published this autumn. Bloomsbury is publishing what appears to be the apotheosis of right-on environmentalism for kids in February, Fantastically Great Women Who Saved The Planet, by Kate Pankhurst.

I love reading with my children and I’m passionate about the environment but my inner sceptic wonders if this worthiness explosion is chasing a phantom market. Who wants heavy-handed moral tales for bedtime? What if eco-doom just generates despair? And how many big picture books are dull-but-worthy Christmas presents that lie unread by real children?

Jill Coleman, the director of children’s books at BookTrust, Britain’s largest reading charity, insists the environmental books boom is driven by “a genuine interest and passion from children”, with publishers following their lead. She believes there are many different books that inspire action, rather than despair, and BookTrust offers recommended reading lists of environmental stories for children of all ages.

“There have always been lots of nature books for kids – wonderful authors like Nicola Davies help children to connect with and understand the natural world – but the recent trend is books which help children think about what they can do,” she says. “Reading is important because it gives children power and agency in all sorts of ways. We need them to feel they can make a difference. I know there are much bigger issues than not buying a plastic bag in a supermarket but when you are nine you can only do what you can do, and you need to feel that you can do something.”

As well as Earth Heroes, Nosy Crow has sold 12,000 UK copies of How To Help A Hedgehog And Protect A Polar Bear, by Jess French and Angela Keoghan, and later this year will publish YouthQuake by Tom Adams and Sarah Walsh, a book about 50 young people who “shook the world”, invariably featuring Thunberg.

“It isn’t just a move by publishers, there is a real hunger for it at the moment,” says Kate Wilson, the managing director and co-founder of Nosy Crow. She believes environmentalism is “becoming less siloed” within publishing as environmentally themed books infiltrate many genres, even the cutesy end of fiction for eight-year-olds with Nosy Crow’s reissue of a Holly Webb eco-series (Maya’s Secret, Izzy’s River, Emily’s Dream, Poppy’s Garden). It was originally published in 2012, when “the world was not ready,” as Wilson puts it.

Wilson admits there is a risk that children’s publishing becomes overly didactic, pushing a vision of how it wants the world to be “because we have a real commitment to the messages that children are given”. Then again, why wouldn’t we want to encourage care for the planet, Wilson argues: children’s publishers perpetually take moral positions, and “never publish books where bullies win, for instance”.

For wildlife journalist and author Ben Hoare, the dilemma is the same as that repeatedly expressed by David Attenborough with his epic natural history TV series. Do writers focus on the wonders of nature and thereby inspire young readers or are they duty-bound to cover the planetary extinction crisis and the climate emergency, even when it risks fuelling climate-anxiety at a young age?

Hoare’s lavish Anthology of Intriguing Animals, which has sold in numbers that authors of adult nature writing can only dream of, goes for inspiration with an awareness of global crises. Like many children’s authors, Hoare tested his writing on his own children. “My two girls are adopted and they grew up in totally bookless households for five years. I’ve watched them discover books and reading fairly late compared to their peers. They were reluctant readers so they would’ve found a traditional encyclopedia a turn-off.” Hoare says he tries to add “whimsy, rhyme, alliteration, quirkiness, things that make you smile” to a conventional encyclopedia-type format. “I’ve found that’s what my children really relate to.”

There is one type of environmental non-fiction Hoare is not a fan of: “Nature activity books that explain how to roll down a hill, look at a sunset or make things out of sticks. Grandparents and parents buy these books because they want to tackle the dreaded screens but I doubt these books get opened. I’m not sure children need to read about these things – just let them go outdoors and discover nature.”

He wonders whether fiction is a more powerful vehicle for raising environmental awareness. His own formative childhood reading included Watership Down, Animals of Farthing Wood and Beatrix Potter, who was never “cutesy”. His daughters have been inspired by Enid Blyton’s The Faraway Tree. “Blyton is laughably dated but this idea of a magical tree really had an impact on my girls. It transformed our walks in the woods. We passed a gnarly oak tree and my daughter said, ‘Look, Dad, there’s the faraway tree’. Fiction is quite a stealthy way of talking to children about big themes.”

Lucy Mangan, the author of Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading, agrees. “Very few children up to the age of 11 can or will read straight non-fiction,” she says. “For the young brain, stories are the way to attract attention and get any message across.”

Mangan fears that the moral instruction in environmental non-fiction is too obvious, not least because “there is only one stance that 99% of scientists and writers would want to take so there’s not much room for doing anything with it”. She says: “Children’s literature began with a desire to instruct but if it had stuck to its guns we wouldn’t still be reading it.” The “golden age” of children’s literature only arrived when authors such as J M Barrie to Edith Nesbit cast off Victorian moralising and wrote from a children’s point of view. “Moralising doesn’t get you very far,” argues Mangan.

Environmental fiction for children aged 10 and above and dystopian novels for young adults are also proliferating in this age of anxiety. At BookTrust, Coleman has particularly enjoyed The Dog Runner by Australian author Bren MacDibble (who lost her home in a wildfire) and Run Wild by Gill Lewis, a vet who tackles complex wildlife themes in her books, from the persecution of birds of prey as well as bear-bile farming and endangered gorillas.

Can this outpouring of environmentalism capture children’s imagination without terrifying them? I test some books on my eight-year-olds. We read Pankhurst’s worthy-sounding Fantastically Great Women Who Saved The Planet. To my surprise, Milly and Esme love it, and I do too: it is funny and interesting, telling stories not just of westerners such as Jane Goodall but also Wangari Maathai, from Kenya, and Isatou Ceesay, from the Gambia. A few days later, Milly tells me they’ve discussed Pankhurst’s story of the Chipko movement in the Indian Himalayas with their teacher. “In the Chipko movement it starts off with one person and then they all protect a whole range of trees from being cut down,” says Milly. “Even a tiny difference makes something big.”

A few nights later, Milly announces she has read Hoare’s hefty Anthology of Intriguing Animals in one evening. She adores the pages edged in gold. “You’ll learn hundreds of lovely new things from that book,” she says.

Hoare aside, I’m still not convinced by the clunky writing in some of the new eco non-fiction. It seems unfair to pick on one but in Miranda Krestovnikoff’s The Sea, for instance, we learn that kelp, for instance, can grow 30 metres tall. How high is that in real life? How do children relate to that? But my views don’t matter. What do the children think of The Sea? After Esme’s tears over ocean plastics, she consoles herself with its stories of otters. “Everyone should try this book,” she says. “If you read the start you think, ‘meh’ but you’ll learn a lot. It’s really good.”

*Title Photo :

Greta and the Giants, inspired by Greta Thunberg, by Zoe Tucker (author) and Zoe Persico (illustrator) and published by White Lion Publishing. Photograph: Courtesy of White Lion Publishing

27 February 2020

The Guardian