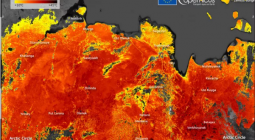

Rain will replace snow as the Arctic’s most common precipitation as the climate crisis heats up the planet’s northern ice cap, according to research.

Today, more snow falls in the Arctic than rain. But this will reverse, the study suggests, with all the region’s land and almost all its seas receiving more rain than snow before the end of the century if the world warms by 3C. Pledges made by nations at the recent Cop26 summit could keep the temperature rise to a still disastrous 2.4C, but only if these promises are met.

Even if the global temperature rise is kept to 1.5C or 2C, the Greenland and Norwegian Sea areas will still become rain dominated. Scientists were shocked in August when rain fell on the summit of Greenland’s huge ice cap for the first time on record.

The research used the latest climate models, which showed the switch from snow to rain will happen decades faster than previously estimated, with autumn showing the most dramatic seasonal changes. For example, it found the central Arctic will become rain dominated in autumn by 2060 or 2070 if carbon emissions are not cut, instead of by 2090 as predicted by earlier models.

The implications of a switchover were “profound”, the researchers said, from accelerating global heating and sea level rise to melting permafrost, sinking roads, and mass starvation of reindeer and caribou in the region. Scientists think the rapid heating in the Arctic may also be increasing extreme weather events such as floods and heatwaves in Europe, Asia and North America by changing the jet stream.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay there,” said Michelle McCrystall at the University of Manitoba in Canada, who led the new research. “You might think the Arctic is far removed from your day-to-day life, but in fact temperatures there have warmed up so much that [it] will have an impact further south.

“In the central Arctic, where you would imagine there should be snowfall in the whole of the autumn period, we’re actually seeing an earlier transition to rainfall. That will have huge implications. The Arctic having very strong snowfall is really important for everything in that region and also for the global climate, because it reflects a lot of sunlight.”

Prof James Screen of the University of Exeter in the UK, who was part of the research team, said: “The new models couldn’t be clearer that unless global warming is stopped, the future Arctic will be wetter, once-frozen seas will be open water, rain will replace snow.”

Scientists already agree that precipitation will increase significantly in the Arctic in future, as more water evaporates from increasingly warmer and ice-free seas. But the research, published in the journal Nature Communications, found this would be hugely dominated by rain, which will more than treble in autumn by 2100 if emissions are not cut.

The scientists concluded: “The transition from a snow- to rain-dominated Arctic in the summer and autumn is projected to occur decades earlier and at a lower level of global warming, potentially under 1.5C, with profound climatic, ecosystem and socioeconomic impacts.”

Snow is important in producing sea ice each winter, so less snow means less ice and more heat absorbed by open oceans. The research shows rain increasing on the southern coast of Greenland. This could further accelerate the sliding of glaciers into the ocean and the consequent rise in sea levels that threatens many coastal areas.

Much of the land in the Arctic is tundra, where the soil has been permanently frozen, but more rain would change that. “You are putting warm water into the ground that might melt the permafrost and that will have global implications, because as we know, permafrost is a really great sink of carbon and of methane,” said McCrystall.

The impacts in the region include the melting of vital ice roads, more floods, and starvation for herds of animals. When rain falls on snow and then freezes, it stops the animals feeding. “The reindeer, caribou and musk oxen can’t break through the layer of ice, so they can’t get to the grass they need to survive and suffer huge die-offs,” she said.

Prof Richard Allan, at the University of Reading in the UK, who was not involved in the research, said: “Exploiting a state-of-the-art set of complex computer simulations, this new study paints a worrying picture of future Arctic climate change that is more rapid and substantial than previously thought. This research rings alarm bells for the Arctic and beyond.”

However, Gavin Schmidt of the Nasa Goddard Institute for Space Studies in the US said the claim of more rapid change was “unsupported”, because some of the new climate models forecast warmer than expected future temperatures.